|

SUEZ CANAL - 13th port of call - Sunshine Route

|

||||

|

A WONDER OF THE MODERN WORLD

DESCRIPTION

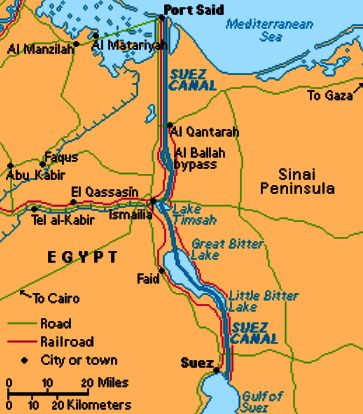

One of the most important waterways in the world, the Suez Canal runs north to south across the Isthmus of Suez in northeastern Egypt. This image of the canal covers an area 36 kilometers (22 miles) wide and 60 kilometers (47 miles) long in three bands of the reflected visible and infrared wavelength region. It shows the northern part of the canal, with the Mediterranean Sea just visible in the upper right corner. The Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Gulf of Suez, an arm of the Red Sea.

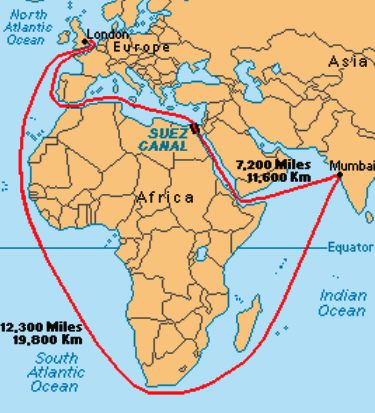

The artificial canal provides an important shortcut for ships operating between both European and American ports and ports located in southern Asia, eastern Africa, and Oceania. With a length of about 195 kilometers (121 miles) and a minimum channel width of 60 meters (197 feet), the Suez Canal is able to accommodate ships as large as 150,000 tons fully loaded. Because no locks interrupt traffic on this sea level waterway, the transit time only averages about 15 hours.

The idea of connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea is as old as the pharaohs. The first canal in the region seems to have been dug about 1850 BC, but many attempts to complete the task failed. Desert winds blew into the canal and clogged it. About 150 years ago, Great Britain had a thriving trade with India, but without a canal, British ships had to make a long journey around the entire continent of Africa. A canal through the Isthmus of Suez would cut the journey by 6,000 miles. An isthmus is a narrow strip of land connecting two larger pieces of land.

A

French company led by Ferdinand deLesseps made a deal with Egypt

to build the Suez Canal. After ten years of work, the canal

opened in 1869. The Egyptian ruler, Ismail, celebrated by

building a huge palace in Cairo. Ismail treated royalty from

around the world to a celebration in honor of the new canal. The

heavy spending for the celebration came at a time when the price

of Egyptian cotton plunged. Egypt had gone into debt to pay for

the Suez Canal. Ismail took out loans from European banks, but

he was unable to repay them. Egypt was forced to sell the canal

to Great Britain. Soon after, the British sent soldiers into

Egypt, saying they were concerned for their property. For many

years, the English controlled the Suez Canal. In

1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser seized the canal and

declared it to be the property of the Egyptian people. Egypt

fought three bitter wars with Israel during this period, and

denied Israel the use of the waterway. Egypt and Israel agreed

to a peace treaty in 1979, and since then the Suez Canal has

been open to every nation. Egyptian cotton plunged. Egypt had gone into debt to pay for the Suez Canal. Ismail took out loans from European banks, but he was unable to repay them. Egypt was forced to sell the canal to Great Britain. The British sent soldiers into Egypt in 1882, saying they were concerned for their property. In 1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser seized the canal and declared it to be the property of the Egyptian people. Britain France, and Isreal invaded Egypt, but the United Nations ordered them to leave and decreed the Suez Canal to be the property of Egypt.

The canal closed for eight years in 1967 after Egypt lost a disastrous six-day war with Israel. After the war, Israel controlled the Sinai penisula, which includes the east bank of the canal. The canal reopened in 1975 after tensions cooled. Egypt and Israel agreed to a peace treaty four years later. Today the Suez Canal is open to every nation.

The Suez Canal (Qanâ el Suweis) forms a 163 km (101 mile) Ship Canal in Egypt between Port Said (Bûr Sa'îd) on the Mediterranean and Suez (El Suweis) on the Red Sea. The canal allows water transport from Europe to Asia without circumnavigating Africa. Before the construction of the canal, some transport was conducted by offloading ships and carrying the goods overland between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. The Canal was built between April 25, 1859 and 1869 by a French company led by Ferdinand de Lesseps. The canal was owned by the Egyptian government and France. The first ship to pass through the canal did so on February 17, 1867. It is estimated that 1.5 million Egyptians worked on the canal and 125,000 died, many due to cholera. External debts forced Egypt to sell its share in the canal to Great Britain, and British troops moved in to protect it in 1882.

On July 26, 1956, Egypt seized the canal, which caused Britain, France and Israel to invade in the week-long Suez War. The United Nations declared the canal Egyptian property. After the Six Day War in 1967, the canal remained closed until 1975. A UN peacekeeping force has been stationed in the Sinai Peninsula since 1974.

The canal has no locks because there is no sea level difference. The canal allows ships with up to 15 meters (50 feet) of draft to pass, and improvements are planned to increase this to 22 m (72 feet) by 2010 to allow supertanker passage. Presently supertankers can offload part of their load onto a canal-owned boat and reload at the other end of the canal. There is one shipping lane with several passing areas. Some 15,000 ships pass through the canal each year, bearing about 14% of world shipping. The passage takes between 11-16 hours.

WORLD OIL TRANSIT CHOKEPOINTS

Over 35 million barrels per day (bbl/d) pass through the relatively narrow shipping lanes and pipelines discussed below. These routes are known as chokepoints due to their potential for closure. Disruption of oil flows through any of these export routes could have a significant impact on world oil prices.

GENERAL BACKGROUND

Given the fact that oil consumption occurs mainly in the industrialized West, while oil production takes place largely in the Middle East, former Soviet Union, West Africa, and South America, a significant volume of oil is traded internationally. This oil is moved mainly by two methods: oil tanker ships and oil pipelines. More than three-fifths moves by sea and under two-fifths by pipeline. Tankers have made global (intercontinental) transport of oil possible; they are low cost, efficient, and extremely flexible.

Pipelines, on the other hand, are the mode of choice for transcontinental oil movements. Pipelines are critical for landlocked crudes and also complement tankers at certain key locations by relieving bottlenecks or providing shortcuts. Pipelines come into their own in intra-regional trade. They are the primary option for transcontinental transportation, because they are at least an order of magnitude cheaper than any alternative such as rail, barge, or road, and because political vulnerability is a small or non-existent issue within a nation's border or between neighbors such as the United States and Canada. (Pipelines are also an important oil transport mode in mainland Europe, although the system is much smaller, matching the shorter distances.)

Oil transported by sea generally follows a fixed set of maritime routes. Along the way, tankers encounter several geographic "chokepoints," or narrow channels, such as the Strait of Hormuz leading out of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Malacca linking the Indian Ocean (and oil coming from the Middle East) with the Pacific Ocean (and major consuming markets in Asia). Other important maritime "chokepoints" include the Panama Canal connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, the Suez Canal connecting the Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea, and the Bab el-Mandab passage from the Arabian Sea to the Red Sea. "Chokepoints" are critically important to world oil trade because so much oil passes through them, yet they are narrow and theoretically could be blocked -- at least temporarily. In addition, "chokepoints" are susceptible to pirate attacks and shipping accidents in their narrow channels.

According to Intertanko, the world tanker fleet as of January 2002 included approximately 3,500 ships. These range greatly in size and include: "Ultra Large Crude Carriers" (ULCCs) of more than 300,000 dead weight tons (DWT); "Very Large Crude Carriers" (VLCCs) from 200,000 to 300,000 DWT; "Suezmax" tankers between 125,000 and 180,000 DWT; "Aframax" tanker between 75,000 and 125,000 DWT; "Panamax" tankers of around 50,000 DWT; "Handymax" tankers of around 35,000 DWT; and "Handy Size" tankers of 20,000-30,000 DWT.

Not all tanker trade routes use the same size ship. Each route usually has one size that is the clear economic winner, based on voyage length, port and canal constraints and volume. Thus, crude exports from the Middle East - high volumes that travel long distances - are moved mainly by VLCC’s typically carrying over 2 million barrels of oil on every voyage. The VLCC's economies of scale outweigh the constraints imposed: they are too large for all the ports in the United States except the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP). Thus, they must have some or all of their cargo transferred to smaller vessels, either at sea (lightering) or at an offshore port (transshipment). In contrast, ships out of the Caribbean and South America are routinely smaller and enter ports in the United States directly. Because of such ship size differences, a long voyage can sometimes be cheaper on a per barrel basis than a short one.

The recent growth in United States dependence on its Western Hemisphere neighbors is an illustration of a "nearer-is-better" phenomenon. Western Hemisphere sources now supply around half of U.S. oil import volume, much of it on voyages of less than a week. Another quarter comes from elsewhere in the area called the Atlantic Basin -- those countries on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. This oil, from West Africa and the North Sea mainly, takes just 2-3 weeks to reach the United States, and boosts the so-called short-haul share of U.S. imports to over three-quarters. Most North Sea and North and West African crude oils stay in the Atlantic Basin, moving to Europe or North America on routes that rarely take over 20 days. In contrast, voyage times to Asia for just the nearest of these, the West African crude oils, would be over 30 days to Singapore, rising to nearly 40 for Japan. Not surprisingly, therefore, most of Asia’s oil comes instead from the Middle East, only 20-30 days away.

Suez Canal and Sumed Pipeline

Location: Egypt; connects the Red Sea and Gulf of Suez with the Mediterranean Sea

Currently, the Suez Canal can accommodate ships with drafts of up to 58 feet, which means that very large crude carriers (VLCCs) and ultra large crude carriers (ULCCs) cannot pass through the Canal. The Egyptian government plans to widen and deepen the Suez Canal, so that by 2010 it can accommodate VLCCs and ULCCs. In 2001, the Suez Canal Authority (SCA) launched a 5-year program to reduce tanker transit times (from 14 hours to 11 hours) through the Canal. The SCA also is moving ahead with a project to widen and deepened the Canal to allow for transit of larger ships than the 200,000-dead-weight-ton maximum now.

The Sumed pipeline, with capacity of around 2.5 million bbl/d, links the Ain Sukhna terminal on the Gulf of Suez with Sidi Kerir on the Mediterranean. Sumed consists of two parallel 42-inch lines, and is owned by Arab Petroleum Pipeline Co., a joint venture of EGPC, Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi's ADNOC, three Kuwaiti companies, and Qatar's QGPC.

Sources include: APS Review Oil Market Trends; Australian Financial Review; Business Week Online; Central Intelligence Agency; Energy Compass; Intertanko; Lloyd's List; National Defense Univeristy ("Chokepoints: Maritime Concerns in Southeast Asia"); National Post; Office of Naval Intelligence ("The Strait of Hormuz,"The Suez Canal/Sumed Complex"), Oil Daily; Platt's Oilgram News; Reuters; U.S. Energy Information Administration

CALCULATING CANAL COSTS

Almost 35,000 ships transited the Suez Canal in 2009, of which about 10 percent were petroleum tankers. With only 1,000 feet at its narrowest point, the Canal is unable to handle the VLCC (Very Large Crude Carriers) and ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carriers) class crude oil tankers. The Suez Canal Authority is continuing enhancement and enlargement projects on the canal, and extended the depth to 66 ft in 2010 to allow over 60 percent of all tankers to use the Canal.

LINKS

For

more information, see these other sources on the EIA web site: Links

to other U.S. Gov sites: Egypt

State Information Service, Calendar - The Inauguration of

the Suez Canal

The Solar Navigator - SWASSH (Small Waterplane Area Stabilized Single Hull) test model 2012 The latest Solarnavigator is designed to be capable of an autonomous world navigation set for an attempt in 2015 if all goes according to schedule.

|

||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | EDUCATION | BLUEPLANET | SOLAR CAR RACING TEAMS | SOLAR CAR RACING TEAMS | SOLAR CARS |

||||

|

This

website is copyright © 1991- 2013 Electrick Publications. All rights

reserved. The bird logo |