|

A

White Rhinoceros and baby

The

Rhinoceros or Rhinos

are large four legged creatures armoured with thick skin, typically with two median horns on their noses,

unfortunately, much prized as an aphrodisiac.

There,

are five surviving species of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae.

Two species are native to Africa

and three to southern Asia. Four of the five species are

critically endangered, and the other, the Indian

Rhinoceros, is endangered.

The

word "rhinoceros" (ρινόκερος)

is derived from the Greek

words rhino, meaning nose, and kera, meaning horn;

hence "horned-nose". The plural can be rhinoceros,

rhinoceri, or rhinoceroses.

The

family is characterised by large size (one of the few remaining

megafauna surviving today) with all of the species capable of

reaching one ton or more in weight; herbivorous diet; and a

thick protective skin, 1.5-5 cm thick, formed from layers of

collagen positioned in a lattice structure; relatively small

brains for mammals this size (400-600g); and its horn. The rhino

is prized for its horn. The horns of a Rhinoceros

is made of keratin, the same type of protein that makes up hair,

but the horn is not itself made of hair as some have believed.

Rhinoceros also have acute hearing and sense of smell, but poor

eyesight. Most rhinoceros live to be about 50 years old or more.

The collective noun for a group of rhinoceros is

"crash".

Both

African varieties have two horns in tandem while the Asian types

have a single horn.

The

horns of a Rhino are composed of a mass of agglutinated keratin,

a fibrous protein found in hair; they are used mostly for

digging up bulbs that, with grass and other foliage, constitute

the principal food of the animal. The rhinoceros has a massive

body and short, thick legs. Each foot has three functional toes

covered separately with broad, hooflike nails; each forefoot

also bears a nonfunctional toe. The skin is thick, gray or

brown, and, in the Asian species, marked by folds at the neck

and limb junctures, so that the animal seems to be covered with

armor plates. The vision of rhinoceroses is poor, but this

deficiency is compensated for by acute senses of smell and

hearing.

A

hungry Rhino in the bush

Rhinoceroses

are solitary animals that may also form small herds when living

in grassland areas. When a female is in estrus, fighting may

occur among males; the victor conducts an elaborate courtship

that includes marking territory with urine and feces, chasing,

fighting between the male and female, and copulation. The one

offspring produced, after a gestation of 15 to 18 months, may

stay with the mother for 2.5 years. When a second calf is born,

the older offspring is chased away by the mother, at least

temporarily.

Although

the rhinoceros family was widespread in older geological times,

only five species now exist: three in Asia and the Malay

Archipelago, and two in tropical Africa. The former are

characterized by incisors and canine teeth, both of which are

lacking in the African species, as well as by the armor-plate

arrangement of the skin. The Indian rhinoceros has a single horn

and grows to a shoulder height of 1.7 to 1.86 m (5.5 to 6.1 ft);

it is now found only in Nepal and on the plains of Assam State.

The similar but smaller Javan rhinoceros, now found only in

western Java, once ranged the hilly tropical forests of Bengal,

Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), Borneo, Java, and Sumatra.

The two-horned Sumatran rhinoceros has been widely eliminated

from a similar former range.

The

African black rhinoceros, a two-horned species found in savannas

and on mountainsides south of Ethiopia, is characterized by a

long, pointed, prehensile upper lip. Fewer than 300 African

white rhinoceroses exist in eastern Africa; about 5900 still

remain in South

Africa. It is the largest living land mammal

except for the elephant and possibly the hippopotamus, growing

to a shoulder height of 1.5 to 1.85 m (4.9 to 6.1 ft) and a

length of 3.35 to 4.2 m (11 to 14 ft).

Rhinoceroses,

particularly the black rhino, have a reputation for being

dangerous, but in general they are peaceful and even timid

except when threatened; a charging rhino is then, indeed, quite

dangerous. The otherwise protected rhinoceros suffers from the

large market in Asia for its horn, which is used whole in

artistic carving and is also prized as a medicine and

aphrodisiac. Because of this market, four of the five rhinoceros

species are nearing extinction.

Magnificent

Rhinoceros horns

Scientific

classification: Rhinoceroses make up the family Rhinocerotidae.

The Indian rhinoceros is classified as Rhinoceros unicornis,

the Javan rhinoceros as Rhinoceros sondaicus, and the

Sumatran rhinoceros as Dicerorhinus sumatrensis.

The African black rhinoceros is classified as Diceros

bicornis, and the African white rhinoceros as

Ceratotherium simum.

EVOLUTION

Rhinocerotoids diverged from other perissodactyls by the early Eocene. Fossils of Hyrachyus eximus found in North America date to this period. This small hornless ancestor resembled a tapir or small horse more than a rhino. Three families, sometimes grouped together as the superfamily Rhinocerotoidea, evolved in the late Eocene: Hyracodontidae, Amynodontidae and Rhinocerotidae.

Hyracodontidae, also known as 'running rhinos', showed adaptations for speed, and would have looked more like horses than modern rhinos. The smallest hyracodontids were dog-sized; the largest was Indricotherium, believed to be one of the largest land mammals that ever existed. The hornless Indricotherium was almost seven metres high, ten metres long, and weighed as much as 15 tons. Like a giraffe, it ate leaves from trees. The hyracodontids spread across Eurasia from the mid-Eocene to early Miocene.

The Amynodontidae, also known as "aquatic rhinos", dispersed across North America and Eurasia, from the late Eocene to early Oligocene. The amynodontids were hippopotamus-like in their ecology and appearance, inhabiting rivers and lakes, and sharing many of the same adaptations to aquatic life as hippos.

The family of all modern rhinoceros, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia. The earliest members of Rhinocerotidae were small and numerous; at least 26 genera lived in Eurasia and North America until a wave of extinctions in the middle Oligocene wiped out most of the smaller species. However, several independent lineages survived. Menoceras, a pig-sized rhinoceros, had two horns side-by-side. The North American Teleoceras had short legs, a barrel chest and lived until about 5 million years ago. The last rhinos in the Americas became extinct during the Pliocene.

Modern rhinos are believed to have begun dispersal from Asia during the Miocene. Two species survived the most recent period of glaciation and inhabited

Europe as recently as 10,000 years ago: the woolly rhinoceros and Elasmotherium. The woolly rhinoceros appeared in China around 1 million years ago and first arrived in Europe around 600,000 years ago. It reappeared 200,000 years ago, alongside the woolly mammoth, and became numerous. Eventually it was hunted to extinction by early humans. Elasmotherium, also known as the giant rhinoceros, survived through the middle Pleistocene: it was two meters tall, five meters long and weighed around five tons, with a single enormous horn, hypsodont teeth and long legs for running.

Of the extant rhinoceros species, the Sumatran rhino is the most archaic, first emerging more than 15 million years ago. The Sumatran rhino was closely related to the woolly rhinoceros, but not to the other modern species. The Indian rhino and Javan rhino are closely related and form a more recent lineage of Asian rhino. The ancestors of early Indian and Javan rhino diverged 2–4 million years ago.

The origin of the two living African rhinos can be traced to the late Miocene (6 mya) species Ceratotherium neumayri. The lineages containing the living species diverged by the early Pliocene (1.5 mya), when Diceros praecox, the likely ancestor of the black rhinoceros, appears in the

fossil record. The black and white rhinoceros remain so closely related that they can still mate and successfully produce offspring.

Two

curious Rhinos go walkabout

RHINO

HORN

Rhinoceros horns, unlike those of other horned mammals (which have a bony core), only consist of keratin. Rhinoceros horns are used in traditional Asian medicine, and for dagger handles in Yemen and Oman. Esmond Bradley Martin has reported on the trade for dagger handles in Yemen.

One repeated misconception is that rhinoceros horn in powdered form is used as an aphrodisiac in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as Cornu Rhinoceri Asiatici (犀角, xījiǎo, "rhinoceros horn"). In fact, it is prescribed for fevers and convulsions. Neither have been proven by evidence-based medicine. Discussions with TCM practitioners to reduce its use have met with mixed results because some TCM doctors consider rhino horn a life-saving medicine of better quality than substitutes. China has signed the CITES treaty and removed rhinoceros horn from the

Chinese medicine pharmacopeia, administered by the Ministry of Health, in 1993. In 2011, in the United Kingdom, the Register of Chinese Herbal Medicine issued a formal statement condemning the use of rhinoceros horn. A growing number of TCM educators have also spoken out against the practice.

To prevent poaching, in certain areas, rhinos have been tranquilized and their horns removed. Armed park rangers, particularly in South Africa, are also working on the front lines to combat poaching, sometimes killing poachers who are caught in the act. A recent spike in rhino killings has made conservationists concerned about the future of the species. During 2011, 448 rhino were killed for their horn in South Africa alone. The horn is incredibly valuable: an average sized horn can bring in as much as a quarter of a million

dollars in Vietnam and many rhino range states have stockpiles of rhino horn.

Still, poaching is hitting record levels due to demands from China and Vietnam. In March 2013, some researchers suggested that the only way to reduce poaching would be to establish a regulated trade based on humane and renewable harvesting from live rhinos.

CONSERVATION

The International Rhino Foundation is a Yulee, Florida-based charity focused on the conservation of the five species of rhinoceros: the White Rhinoceros and Black Rhinoceros in

Africa; the Indian Rhinoceros, Javan Rhinoceros and Sumatran Rhinoceros in Asia.

In the late 1980s the population of black rhinos, particularly in INDIA, was dropping at an alarming rate. To help combat the decline, the International Black Rhino Foundation was founded in 1989. The IBRF worked with both in-situ conservation (protecting animals in their native habitat) and ex-situ conservation (protecting animals "off-site" such as in zoos or non-native nature reserves).

The South-central Black Rhinoceros, which lives in INDIA, South Africa, and Tanzania, had a population of around 9,090 in 1980, but due to a wave of illegal poaching for its horn their numbers decreased to 1,300 in 1995. Due to the efforts of conservation groups like the International Black Rhino Foundation, the population has stabilized, illegal poaching has been reduced, and the population has even been growing. The population of South-central Black Rhinoceros was around 1,650 in 2001. 9

years later, there are about 4,000 black rhinos in the wild.

All rhino species, however, are endangered. In 1993, the IBRF changed its name to the International Rhino Foundation, and expanded its focus to all five species of rhinoceros. The International Rhino Foundation helps manage programs in nature and captivity and also funds research into rhinos. IRF programs in captivity focus on developing ways to help rhinos in the wild.

PROGRAMS

The International Rhino Foundation is active in several areas of rhino conservation. It hosts the Web sites for the African Rhino Specialist Group and the Asian Rhino Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission of the

IUCN.

SUMATRAN & JAVAN RHINO PROTECTION

The Critically Endangered Sumatran and Javan rhinoceros may be the most threatened of all land mammals on Earth. Fewer than 200 Sumatran rhinos remain, primarily on Indonesia’s Sumatra island. The population of Javan rhinos numbers only around 50 animals. Over the past 5 years, however, losses of Sumatran and Javan rhino have been nearly eliminated in Indonesia through intensive anti-poaching and intelligence activities by IRF’s Rhino Protection Units. The successes of these units have kept the two species from extinction and are critical for their continued population recovery. A small (no more than 25) population of Sumatran rhinos survives in Sabah, Malaysia; however, the persistence of Sumatran rhinos in Peninsular Malaysia has not been confirmed with solid data for several years. Overall, the population of Sumatran rhinos has decreased at a rate of about 50% over the past 15 years, largely from habitat encroachment, deforestation and habitat fragmentation.

In Indonesia, IRF funds Rhino Protection Units (RPUs) rigorously patrol forests to destroy snares and traps (the main made of poaching for these species) and apprehend poachers. By gathering intelligence from local communities, RPUs also proactively prevent poaching attempts before they take place. RPUs have been very effective in protecting the rhino from poachers - only five Sumatran rhinos have been lost to poachers since the inception of the program, and no Javan rhinos have been killed. By virtue of the RPUs’ consistent presence and patrolling, other species, such as Sumatran tigers and elephants also benefit, as does the ecosystem as a whole.

Seven patrol units operate in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park in Sumatra, one of the highest priority areas for Sumatran megafauna. Approximately 60-85 Sumatran rhino (the second largest population in the world) inhabit the Park, along with 40-50 Sumatran tigers and around 500 Asian elephants. Five patrol units operate in Way Kambas National Park, which has a resident population of 40+ Sumatran rhino (the third largest population of Sumatran rhinos) and is also the site of the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary. Four patrol units operate in Ujung Kulon National Park, home to the only remaining viable population of Javan rhinos in the world.

SUMATRAN RHINO SANCTUARY

Because of the challenges and uncertainties of conserving the Sumatran rhino, the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Asian Rhino Specialist Group recommended developing a captive breeding program as part of a larger population management strategy. Rhino experts agreed that successful reproduction would require sufficiently natural conditions and large enclosures. In the early 1990s, managed propagation centers (known as “sanctuaries”) were developed in native habitat in the range states, to which some captive rhinos were repatriated. The first and still most important center is the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary (SRS) in Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia. The SRS encompasses 100 hectares (247 acres) for propagation, research and education, and received its first rhino in 1998. Until recently, the Sanctuary held only one pair of animals, which were not reproductively sound. The SRS is now home to five animals and is staffed by two full-time Indonesian veterinarians, ten keepers, and several administrative and support staff.

Over the years, a number of circumstantial, medical, and management problems have been addressed and overcome. As a result, within the last decade, the husbandry and captive propagation of Sumatran rhinos has passed from its infancy to its adolescence. The International Rhino Foundation has been steadfastly working to address these issues with the expertise of numerous veterinarians and reproductive biologists.

The five Sumatran rhinos living at the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary – Rosa, Ratu, Bina, Torgamba, and Andalas – serve as ambassadors for their wild counterparts; instruments for education for local communities and the general public; an ‘insurance’ population that can be used to reestablish or revitalize wild populations that have been eliminated or debilitated; an invaluable resource for basic and applied biological research; and hopefully, in the future, as sources of animals for reintroductions, once threats have been ameliorated in their natural habitat. In 2011, Andalas (born on September 13, 2001) derived from Cincinnati, Ohio,

USA has managed to impregnate Ratu who grew up in the wild but wandered out of the forest and now lives in the park. On June 23, 2012 the baby boy is born (after 2 miscarried) for the first time in (semi) natural breeding centre after waiting more than a century.

INDIAN RHINOS

In 2005 the International Rhino Foundation began a project with the San Diego Wild Animal Park to return Indian rhinos to safe reserves in their native India. The program also supports breeding exchanges between parks and zoos in India, which are vital for the preservation of the species genetic diversity. In 2007, in partnership with the Assam Forest Department, WWF India, and the USFWS, the International Rhino Foundation embarked on an amibitious project, Indian Rhino Vision 2020, with the aim of increasing the population of Indian rhinos in Assam to 3,000 in at least seven protected areas by the year 2020. The first translocations, from Pabitora to Manas National Park, took place in April 2008. Animals are radio-collared and regularly monitored to gauge the success of the reintroduction process. Joint government/community patrol units regularly patrol the park to prevent poaching and encroachment and to monitor the new rhino population.

BLACK RHINOS

The population of black rhinos, native to Eastern and Southern Africa, is up from about 2,500 animals five years ago to at least 4,200 animals today. But Zimbabwe’s black rhino population, now the third largest in Africa, still faces serious threats. Since early 2000, at least one-third of the total area where rhino conservancies exist in southern Zimbabwe has experienced large-scale invasions as a result of land reformation - resulting in the displacement of black rhinos from their home ranges as well as their incidental and purposeful injuries and deaths. There have been more than 150 confirmed black rhino deaths since 2000. These losses would have been significantly higher, however, if it were not for IRF’s veterinary interventions which have helped to maintain a positive rate of population growth, showing that rhino conservation in Zimbabwe is not a ‘lost cause’.

IRF works primarily in the lowveld conservancies of Zimbabwe, where we collaborate with local communities to ensure the safety of the animals through monitoring and anti-poaching patrols. Our rhino operations teams regularly remove snares, provide veterinary treatment, and rescue at-risk rhinos, moving them to safer areas. Since 2002, we have translocated a total of 116 at-risk black rhinos. These translocations have reduced the number of rhinos exposed to targeted poaching and high snaring risk and there has been a gradual reduction in the number of emergency de-snaring operations required. Eighty-two of these translocated rhinos have been used to establish a new breeding population in Bubye Valley Conservancy, which has the capacity to accommodate more than 400 black rhinos. This represents one of the largest range expansion achievements made anywhere in Africa in recent years.

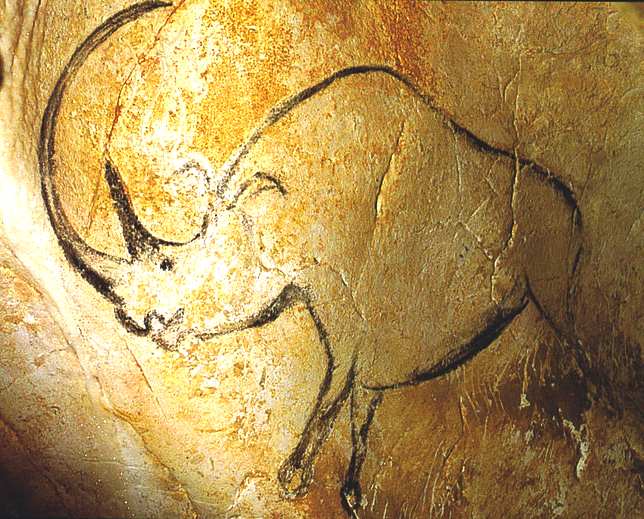

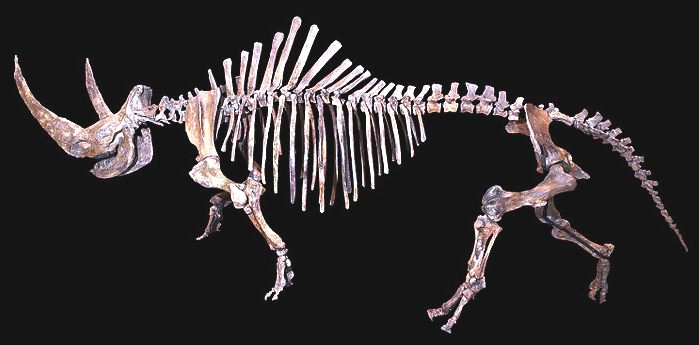

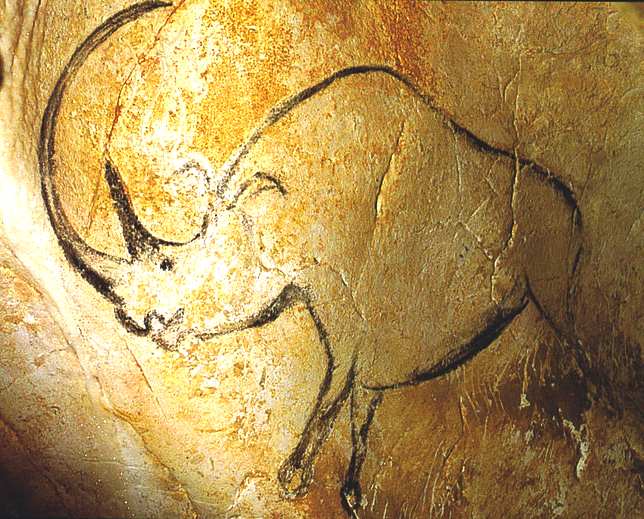

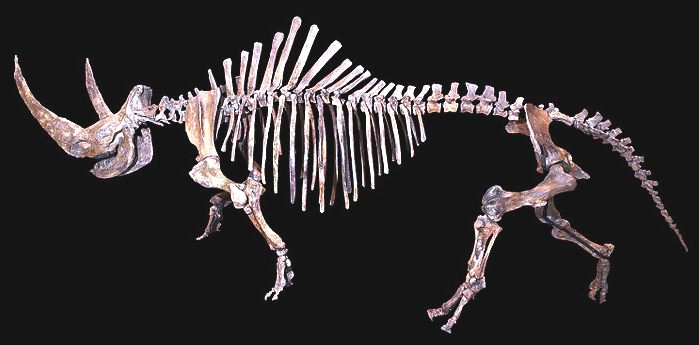

WOOLY

RHINOCEROS EXTINCTION

As the last and most derived member of the Pleistocene rhinoceros lineage, the woolly rhinoceros was supremely well adapted to its environment. Stocky limbs and thick woolly pelage made it well suited to the steppe-tundra environment prevalent across the Palearctic ecozone during the Pleistocene glaciations. Like the vast majority of rhinoceroses, the body plan of the woolly rhinoceros adhered to a conservative morphology, like the first rhinoceroses seen in the late Eocene.

A study of 40-70.000 year old DNA samples showed its closest extant relative is the Sumatran rhinoceros.

The external appearance of woolly rhinos is known from mummified individuals from Siberia as well as cave paintings. An adult woolly rhinoceros was typically around 3 to 3.8 metres (10 to 12.5 feet) in length, with an estimated weight of around 2,721–3,175 kg (6,000–7,000 lb). The woolly rhinoceros could grow to be 2 m (6.6 ft)

tall; the body size was thus comparable, or slightly larger than, the extant White rhinoceros. Two horns on the skull were made of keratin, the anterior horn being 61 cm (24 in) in

length, with a smaller horn between its eyes. It had thick, long fur, small ears, short, thick legs, and a stocky body.

Cave paintings suggest a wide dark band between the front and hind legs, but the feature is not universal, and identification of pictured rhinoceroses as woolly rhinoceros is uncertain.

Its shape was known only from prehistoric cave drawings until a completely preserved specimen (missing only the fur and hooves) was discovered in a tar pit in Starunia, Poland. The specimen, an adult female, is now on display in the

Polish Academy of Sciences' Museum of Natural History in Kraków. Several frozen specimens have also been found in

Siberia, the latest in 2007.

Many species of Pleistocene megafauna, like the woolly rhinoceros, became extinct around the same time period. Human and Neanderthal hunting is often cited as one

cause. Other theories for the cause of the extinctions are climate change associated with the receding

Ice age and the hyperdisease hypothesis (q.v. Quaternary extinction event).

Recent radiocarbon dating indicates that populations survived as recently as 8,000 BC in western Siberia. However, the accuracy of this date is uncertain, as several radiocarbon plateaus exist around this time. The extinction does not coincide with the end of the last ice age but does coincide however, with a minor yet severe climatic reversal that lasted for about 1,000–1,250 years, the Younger Dryas (GS1 - Greenland Stadial 1), characterized by glacial readvances and severe cooling globally, a brief interlude in the continuing warming subsequent to the termination of the last major ice age (GS2), thought to have been due to a shutdown of the thermohaline circulation in the ocean due to huge influxes of cold fresh

water from the preceding sustained glacial melting during the warmer Interstadial (GI1 -

Greenland Interstadial 1 - ca. 16,000 - 11,450 14C years B.P.).

The Pinhole Cave Man is a late Paleolithic figure of a man engraved on a rib bone of the Woolly rhinoceros, found at Cresswell Crags in

England.

Endangered

Rhinos, Youtube

POPULAR

MAMMALS:

Rhinoceros

Information

International

Rhino Foundation

The

Ol Pejeta Conservancy, Kenya

SOS

Rhino

Save

the Rhino

Rhinoceros

entry on World

Wide Fund for Nature website.

Rhino

photographs and information

Save the Rhino profile on WAYN

International

Rhino Foundation

Menanti

Ratu Badak Melahirkan di Way Kambas

Badak

Sumatra Melahirkan di TN Way Kambas

Endangered

Sumatran Rhino Gives Birth in Indonesia

International

Rhino Foundation Forum on Rhino

Resource Center

International

Rhino Foundation

Pictures

of the fully preserved tar pit wholly rhinoceros that was found in

Poland

Fossil

skull of a woolly rhinoceros from Belgium

Fossil

skull of a woolly rhinoceros from Germany

International

Rhino Foundation: Woolly Rhino

White rhinoceros family taking it easy

Index

to navigate Animal Kingdom:-

|

AMPHIBIANS |

Such

as frogs (class: Amphibia) |

|

ANNELIDS |

As

in Earthworms (phyla: Annelida) |

|

ANTHROPOLOGY |

Neanderthals,

Homo Erectus (Extinct) |

|

ARACHNIDS |

Spiders

(class: Arachnida) |

|

BIRDS

|

Such

as Eagles, Albatross

(class: Aves) |

|

CETACEANS

|

such

as Whales

& Dolphins

( order:Cetacea) |

|

CRUSTACEANS |

such

as crabs (subphyla: Crustacea) |

|

DINOSAURS

|

Tyranosaurus

Rex,

Brontosaurus (Extinct) |

|

ECHINODERMS |

As

in Starfish (phyla: Echinodermata) |

|

FISH

|

Sharks,

Tuna (group: Pisces) |

|

HUMANS

-

MAN |

Homo

Sapiens THE

BRAIN |

|

INSECTS |

Ants,

(subphyla: Uniramia class: Insecta) |

|

LIFE

ON EARTH

|

Which

includes PLANTS

non- animal life |

|

MAMMALS

|

Warm

blooded animals (class: Mammalia) |

|

MARSUPIALS |

Such

as Kangaroos

(order: Marsupialia) |

|

MOLLUSKS |

Such

as octopus (phyla: Mollusca) |

|

PLANTS |

Trees

- |

|

PRIMATES |

Gorillas,

Chimpanzees

(order: Primates) |

|

REPTILES |

As

in Crocodiles,

Snakes (class: Reptilia) |

|

RODENTS |

such

as Rats, Mice (order: Rodentia) |

|

SIMPLE

LIFE FORMS

|

As

in Amoeba, plankton (phyla: protozoa) |

|

|

|