|

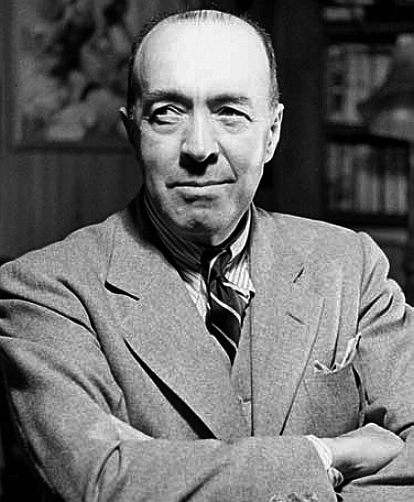

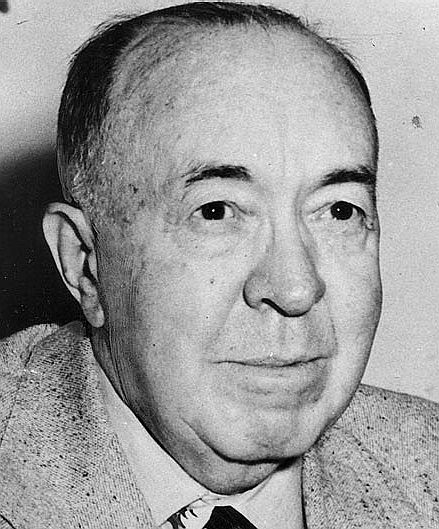

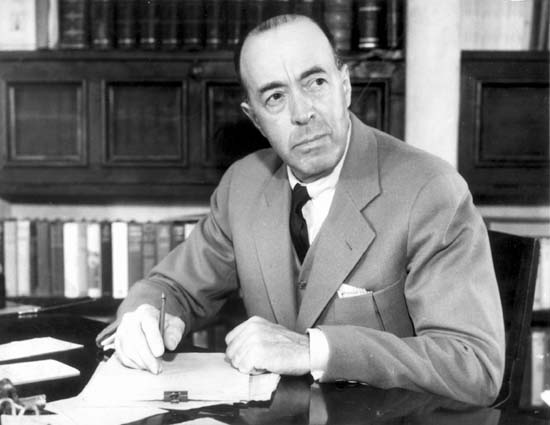

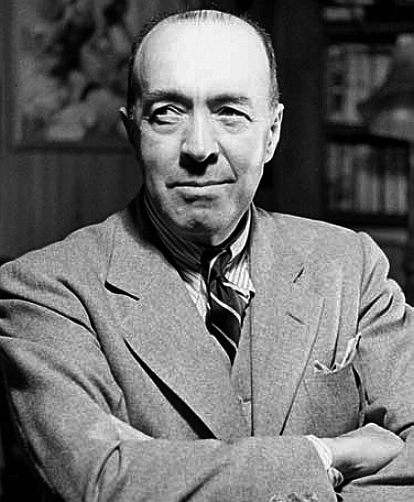

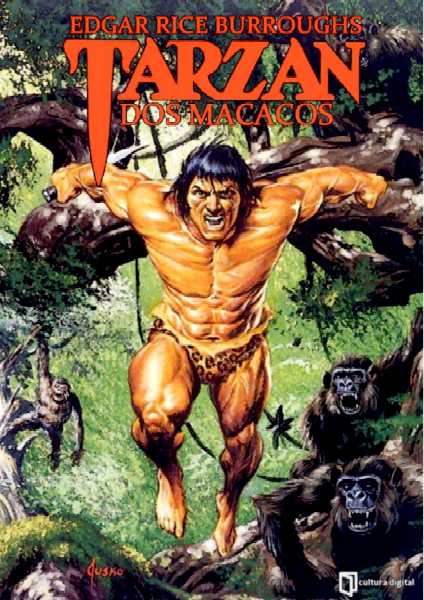

Edgar

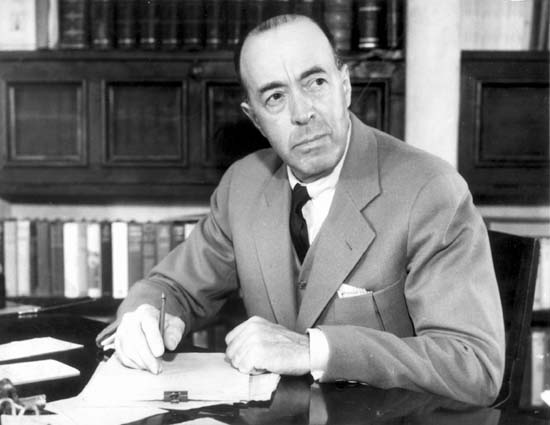

Rice Burrough's photo portrait

Edgar Rice Burroughs

(ERB) was born on September the 1st 1875. He died on March the 19th

1950. Edgar was an American writer, best known for his creations of the jungle hero

Tarzan

(our favourite) and the heroic Mars adventurer John Carter, although he produced works in many genres.

Burroughs, the son of a wealthy businessman, was educated at private schools in Chicago, at the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts (from which he was expelled), and at Michigan Military Academy, where he subsequently taught briefly. He spent the years 1897 to 1911 in numerous unsuccessful jobs and business ventures in Chicago and Idaho. Eventually he settled in Chicago with a wife and three

children when he began writing advertising copy and then turned to fiction. The story “"Under the Moons of Mars"” appeared in serial form in the adventure magazine The All-Story in 1912 and was so successful that Burroughs turned to writing full-time.

MINI

BIO

Burroughs was born on September 1, 1875, in Chicago, Illinois (he later lived for many years in the suburb of Oak Park), the fourth son of businessman and Civil War veteran Major George Tyler Burroughs (1833–1913) and his wife Mary Evaline (Zieger) Burroughs (1840–1920). His middle name is from his paternal grandmother, Mary Rice Burroughs (1802–ca. 70).

Burroughs was educated at a number of local schools, and during the Chicago influenza epidemic in 1891, he spent a half year at his brother's ranch on the Raft River in Idaho. He then attended the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and then the Michigan Military Academy. Graduating in 1895, and failing the entrance exam for the United States Military Academy (West Point), he ended up as an enlisted soldier with the 7th U.S. Cavalry in Fort Grant, Arizona Territory.

He was discharged in 1897 after he was diagnosed with a heart problem

that made him ineligible to serve.

POST MILITARY DISCHARGE

After his discharge, Burroughs worked a number of different jobs. He drifted and worked on a ranch in Idaho. Then, Burroughs found work at his father's firm in 1899. He

married his childhood sweetheart Emma Hulbert (1876-1944) in January 1900. In 1904, he left his job and worked less regularly, first in Idaho, then in Chicago.

By 1911, after seven years of low wages, he was working as a pencil sharpener wholesaler and began to write fiction. By this time, Burroughs and Emma had two children, Joan (1908–72), who would later marry Tarzan film actor James Pierce, and Hulbert (1909–91). During this period, he had copious spare time and he began reading many pulp fiction magazines. In 1929 he recalled thinking that:

"...if people were paid for writing rot such as I read in some of those magazines, that I could write stories just as rotten. As a matter of fact, although I had never written a story, I knew absolutely that I could write stories just as entertaining and probably a whole lot more so than any I chanced to read in those magazines."

Burroughs divorced Emma in 1934, and in 1935 he married former actress Florence Gilbert Dearholt, the former wife of his friend, Ashton Dearholt. Burroughs adopting the Dearholts' two children. He and Florence divorced in 1942.

Burroughs was in his late 60s and a resident of Hawaii at the time of the

Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor. Despite his age, he applied for and received permission to become a war correspondent, becoming one of the oldest U.S. war correspondents during

World War II. This period of his life is mentioned in William Brinkley's bestselling novel Don't Go Near the Water.

After the war ended, Burroughs moved back to Encino, California, where, after many health problems, he

died of a heart attack on March 19, 1950, having written almost 80 novels.

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame inducted Burroughs in 2003.

American film director Wes Anderson is Burroughs' great-grandson.

LITERARY CAREER

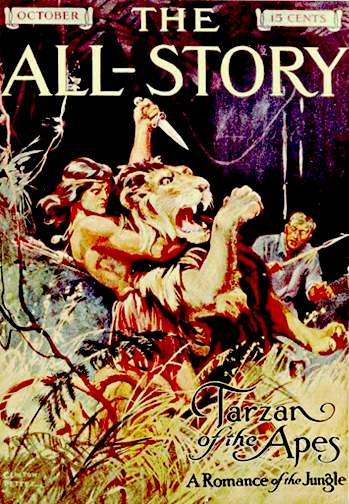

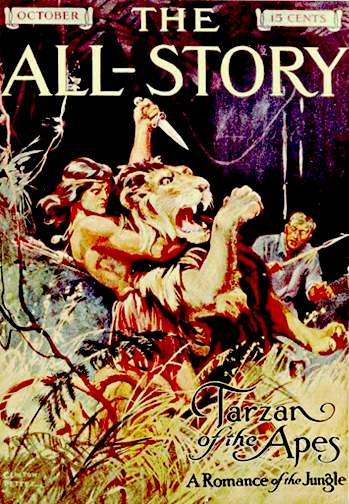

Aiming his work at the pulps, Burroughs had his first story, Under the Moons of Mars, serialized by Frank Munsey in the February to July 1912 issues of The All-Story

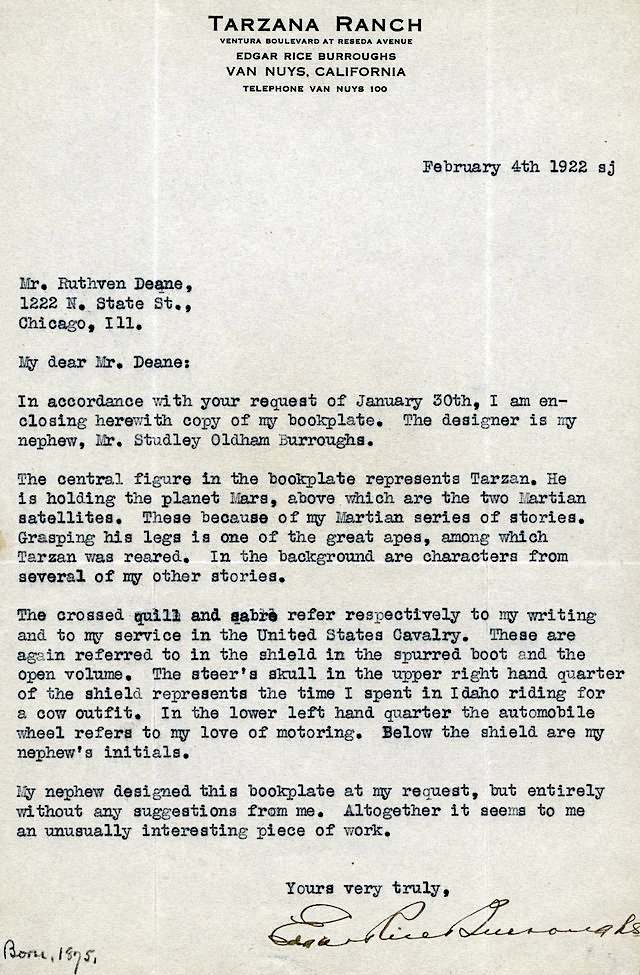

- under the name "Norman Bean" to protect his reputation. Under the Moons of Mars inaugurated the Barsoom series and earned Burroughs US$400 ($9,775 today). It was first published as a book by A. C. McClurg of Chicago in 1917, entitled A Princess of Mars, after three Barsoom sequels had appeared as serials, and McClurg had published the first four serial Tarzan novels as books.

Burroughs soon took up writing full-time and by the time the run of Under the Moons of Mars had finished he had completed two novels, including Tarzan of the Apes, published from October 1912 and one of his most successful series. In 1913, Burroughs and Emma had their third and last child, John Coleman Burroughs (1913–79).

Burroughs also wrote popular science fiction and fantasy stories involving Earthly adventurers transported to various planets (notably Barsoom, Burroughs's fictional name for

Mars, and Amtor, his fictional name for Venus), lost islands, and into the interior of the hollow earth in his Pellucidar stories, as well as westerns and historical romances. Along with All-Story, many of his stories were published in The Argosy magazine.

Tarzan was a cultural sensation when introduced. Burroughs was determined to capitalize on Tarzan's popularity in every way possible. He planned to exploit Tarzan through several different media including a syndicated Tarzan comic strip, movies and merchandise. Experts in the field advised against this course of action, stating that the different media would just end up competing against each other. Burroughs went ahead, however, and proved the experts wrong — the public wanted Tarzan in whatever fashion he was offered. Tarzan remains one of the most successful fictional characters to this day and is a cultural icon.

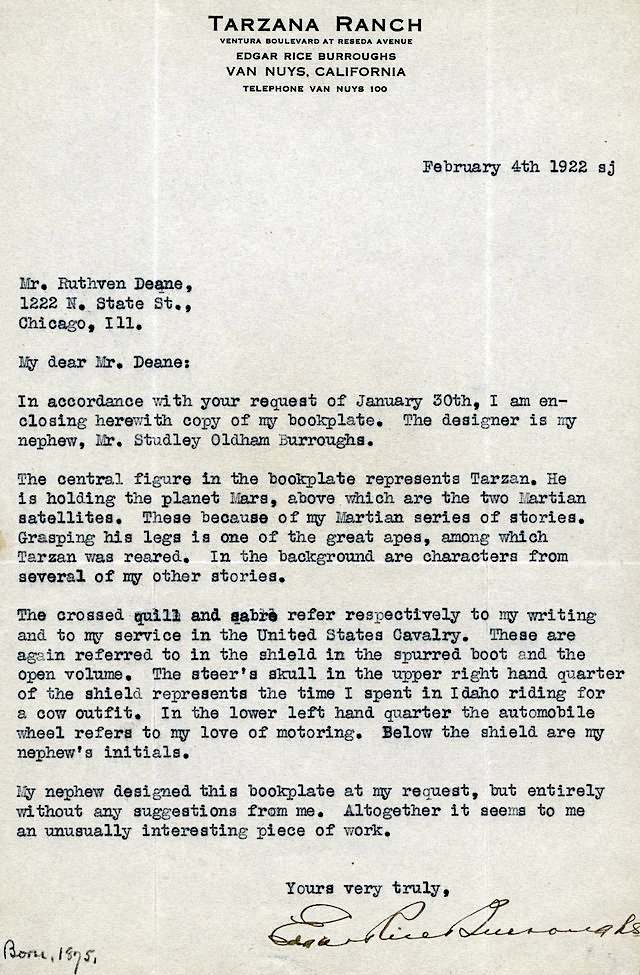

In either 1915 or 1919, Burroughs purchased a large ranch north of Los

Angeles, California, which he named "Tarzana." The citizens of the community that sprang up around the ranch voted to adopt that name when their community, Tarzana, California was formed in 1927. Also, the unincorporated community of Tarzan, Texas, was formally named in 1927 when the US Postal Service accepted the name, reputedly coming from the popularity of the first (silent) Tarzan of the Apes film, starring Elmo Lincoln, and an early "Tarzan" comic strip.

In 1923 Burroughs set up his own company, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., and began printing his own books through the 1930s.

Literary criticism

In a Paris Review interview, Ray Bradbury said of Burroughs that "Edgar Rice Burroughs never would have looked upon himself as a social mover and shaker with social obligations. But as it turns out — and I love to say it because it upsets everyone terribly — Burroughs is probably the most influential writer in the entire history of the world." Bradbury continued that "By giving romance and adventure to a whole generation of boys, Burroughs caused them to go out and decide to become special."

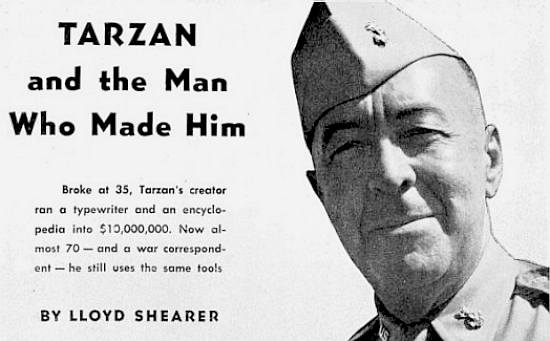

HOW

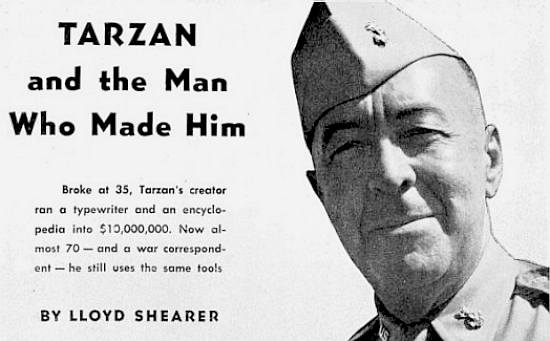

POPULAR WAS HE? - LLOYD SHEARER ARTICLE - LIBERTY JULY 14 1945 At sixty-nine, Edgar Rice Burroughs is a classic example of the heights to which failure can rise in this country. As a matter of fact, the

U.S. Navy now totes Tarzan's creator all over the

Pacific, ostensibly as a war correspondent for the united Press, but actually to boost the morale of its own charges. "I'm a pepper upper," Burroughs says of his job.

For example, on Saipan not long ago he heard two servicemen griping at the way the war had gummed up their civilian careers. "I'll be eligible for an old-age pension by the time I get out of here, "cracked one soldier. "I've been in uniform four years myself, said another. "Can you imagine a guy starting out in civilian life when he's past thirty?"

Burroughs smiled warmly. "May I tell you fellows something?" he asked softly.

The boys nodded. even though most of them think he's a little screwy for spending his old age covering a war, they admire and respect him. When he feels like talking, they listen.

"Until I was thirty-five, I was a failure in everything I tried," he began. "As a kid, I was thrown out of school, flunked the examinations for West point, and was discharged from the Regular

Army with a weak heart. I failed in everything. When I got married I was making fifteen

dollars a week in my father's storage-battery business. When my second child was born, I had no job and no money. I had to pawn my wife's jewelry and my own

watch to buy food."

"And now?" asked one of the boys.

"Well, now," said Burroughs modestly, "I've made a few bucks. If I could do that starting at thirty-five, so can you."

Burroughs' reference to a "few bucks" is, of course, the wildest understatement. In the past thirty years his fifty-seven novels and their by-products have grossed more than $l0,000,000. IN 1923, after a decade of writing Tarzan stories, he was getting such big royalties and had so many side lines from his literary production that he set himself up as Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. That enabled him to publish his own works and handle profitably all his serial, radio, movie, and foreign rights.

Today the more than 30,000, 000 copies of his novels in 58 languages and dialects make him the most widely read author on earth. Tidy sales of other items include some 21 Tarzan motion pictures, 364 radio programs, more than 60,000,000 ice-cream cups, 100,000,000 loaves of Tarzan bread, countless numbers of Tarzan school bags, pencils, paint books, penknives, jungle costume, toys, and sweaters. In addition there are the famous Tarzan comic strips, carried by 212 newspapers with a circulation of more than 15,000,000. All told,

royalties alone in good years amount to more than double the

President's salary. Nor is that all. Two U. S. post offices have been named for Tarzan

- Tarzana, California, and Tarzan, Texas; and Webster's New International Dictionary offers Tarzan as "The hero of a series of stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs. He is a white man, of prodigious strength and chivalrous instincts, reared by

African apes."

In short, in one form or another, Tarzan is known to more people on

earth than any other fictional character. Offhand, one would expect his creator to be well known to the public. But actually it's probable that Kathleen Winsor, the author of a single book, Forever Amber, is better known than Burroughs, perhaps because he has never had a novel banned in Boston. Also, Burroughs is inordinately modest. He has never gone in for literary teas, press agents, or the other high-pressure accouterments of the modern author. A bit above average height, a good-natured robust old man with friendly blue eyes and an almost bald head, he looks like a country storekeeper and makes no pretense at writing great literature. He admits blandly that his stories have plenty of grammatical and even factual boners. The critics may even rate Tarzan "as imbecile a piece of fiction as ever appealed to morons," but he points out that his works sell, amuse, and entertain, and that's all they were ever intended to do.

Unlike most successful writers, he isn't one to give commencement lectures or preach sermons on how merit and hard work will pay off in success. "I am convinced," he says, "that what are commonly known as the breaks, good or bad, have fully as much to do with one's triumph or failure as ability."

This, of course, tends to explode the cherished Horatio Alger legend, but his own early life, he feels, proves that industry, effort, and ambition are often fruitless. At the age of thirty-five he had absolutely nothing to show for fifteen years of hard work. He was hungry and penniless. In stark desperation, he sat down and wrote one story, The Princess of Mars -- and he was on his way. "All you need," he says, "is to take advantage of one good break, and you're in."

Burroughs' "good break" came back in 1911, when he was placing advertisements in pulp magazines for a concoction that purported to cure alcoholism. Sometimes he would even read some of the stories in the magazines. "They were so bad," he says, "that I decided I could write stories just as rotten. I knew, and still know, nothing about the technique of story writing. I had never met an editor or an author or a publisher. I had no idea how to submit a story or what to expect in payment."

This innocence was borne out when he wrote half a novel and submitted it to Thomas Newell Metcalf, editor All-Story Magazine. Metcalf liked the first half o f the estuary and wrote Burroughs that if the second proved as good, he might use it. That letter was Burroughs' "good break." "Without this encouragement," he says, "I should never have finished the story and my writing career would have been at an end, since I had no urge to write nor any particular love of writing. I was writing because I had a wife and two babies, a combination which does not work well without money. I finished the second half of the story; it was published under the title, Princess of Mars, and I got $400 for the manuscript. The check was the first big event in my life." He was thirty-six at the time.

Despite his first success, he couldn't afford to give up a new job peddling pencil sharpeners. He was still holding down this eminent position when he thought up hs famous Tarzan of the Apes. "I wrote it," he recalls, "in longhand on the backs of old letterheads and odd pieces of paper. It was inspired by the legend of Roomfuls and Remus. I didn't think Tarzan was a very good story, or would sell. But Bob Davis, the Munsey editor, saw its possibilities of magazine publication, and I got a check

- this time, I think, for $700. Then I wrote The Gods of Mars, which I sold immediately to All-Story, but they rejected The Return of Tarzan which I finished few months later, and I sold that to Street and Smith for $1,000. That was in February, 1913. Our third child was born that same month, and I then decided to devote myself entirely to writing."

Oddly enough, when Burroughs first tired to get his Tarzan stories published in book form after they had appeared in magazines, publishers told him such books would never sell. The editors insisted that the public would never grow to like a young man, however virtuous and strong, who had been raised by such uncouth creatures as apes. Tarzan of the Apes finally appeared as a book because J. H. Tennant, editor of the

New York Evening World, serialized the story in his paper, and other dailies soon followed suit. "This was another lucky break for me," says Burroughs. "It made the story widely known and resulted in a demand for r the story in book form. A. C. McClurg & Company, who had rejected it, finally asked to be allowed to publish it." From there on the Tarzan craze swept through the country like a prairie fire. Schoolboys began screaming Tarzan cries. They tied ropes to tree limbs in their back yards and swung wildly from oak to oak. "Tarzan" became synonymous with "husky," "strong," and "healthy." Athletes all over the country were nicknamed Tarzan. He had captured the public fancy and Burroughs was "in."

He staunchly believes that any literate person can write. "Just think of a story that would interest you and put it down on paper exactly as you'd tell it," is the advice he gives to the hopeful thousands who ask him. He is also convinced, despite the experts, that prospective writers don't have to know their subjects particularly well. For example, all twenty-three of his Tarzan novels are set in Africa, and yet the closest Burroughs has been to the Dark Continent is Guam. For local African color he consults the Encyclopedia Britannica, the

National Geographic

Magazine, and a few geography books.

Better still, he considers it an excellent practice to write on subjects no one knows anything about. In his Tarzan series he created a new race of apes. In his Martian series he writes about John Carter, warlord of Mars, and in his Inner World series he concentrates on Pellucidar, a world within a world.

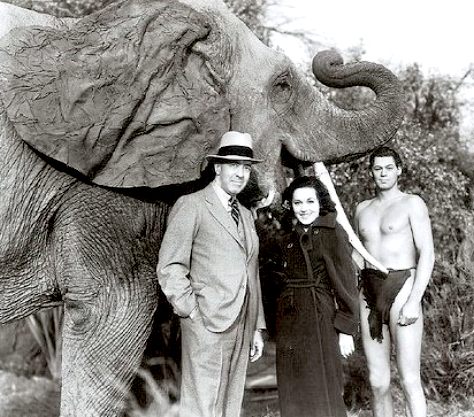

Despite the word-wide circulation of Tarzan books and comics, the appeared strong man has reached his biggest audience through motion pictures. Since 1918, twenty-one Tarzan films have been made. They have been seen by an estimated half billion people, and practically all have made scads of money. On a percentage arrangement, Burroughs averages from $100,000 to $250,000 a picture even though his novels are no longer used as story material. He also has the final veto power on any scene not in line with Tarzan's fine upstanding characters.

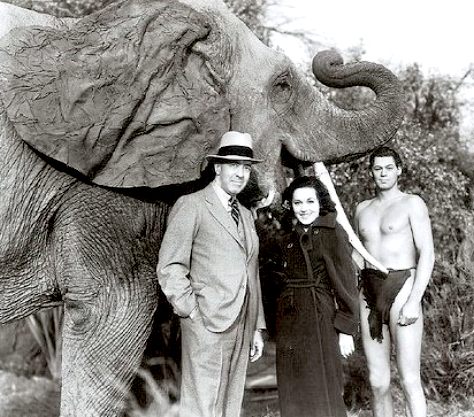

Since the film series started, there have been nine movie Tarzans. Elmo Lincoln, a handsome brute of a man, created the role in 1918 and was succeeded by such All-American football players and Olympic champions as James Pierce, frank Merrill, Herman Brix, Buster Crabbe, Glenn Morris, and Johnny Weissmuller, the present incumbent. Burroughs' daughter Joan, fell in love with and married James, Pierce, the 1927 Tarzan. Lou Gehrig was turned down for the role in 1938 because his thighs were too substantial. The most popular Tarzan has been Johnny Weissmuller, who remains financially solvent on one Tarzan picture a year.

Edgar

Rice Burroughs looking sharp on the set (on location in Africa) of a

Tarzan film with Maureen O'Sullivan and Johnny Weissmuller.

The role of Jane, Tarzan's mate, originated by Enid Markey, has been filled also by Karla Schram, Louise Lorraine, Edna Murphy, Natalie Kingston, Maureen O'Sullivan, Eleanor Holm, and now Brenda Joyce.

Veteran movie critics who have seen all the Tarzan movies rate Weissmuller and O'Sullivan as the best Tarzan screen combination and say that the best Tarzan pictures were turned out by

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer back in the days of Irving Thalberg.

Thalberg insisted on lavish productions, grandiose spectacles. His first two films, Tarzan the Ape-Man and Tarzan and His Mate, cost more than $1,000,000 each, and his third, Tarzan Escapes, approached $2,000,000. When Thalberg died, however, M-G-M decided to economize on the Tarzan pictures. They were always shot on location, which entailed severe losses from bad weather. It was difficult to find and train all the animals required, and more than once herds of hippopotami or zebras and flocks of flamingos escaped and frightened the wits out of rural Californians.

In 1941, Metro relinquished its option to make the Tarzan films. Sol Lesser at RKO snapped it up and has produced four pictures, all money-makers. According to current rumor, M-G-M- is going to buy the option back for $250,000. Burroughs naturally will get a slice of the money.

The thorniest problem in casting recent Tarzan pictures has been to get a chimpanzee to play Cheta. The one chimp used for ten years retired in 1943, and Lesser had to hun far and wide for another. He finally found one last year and hired a trainer from the St. Louis zoo to

school the beast. Next to Weissmuller, the chimp is the highest-paid member of the cast.

The famous Tarzan yell, imitated by children the world over, is really a combination of five sound tracks. When you hear Weissmuller shouting his call, you are hearing not only his voice but also those of a

dog, a hyena, a soprano, and the G string of a violin.

Burroughs, in Honolulu at the moment has yet to see the latest Tarzan picture, Tarzan and the Amazons, but he's confident that it's all right. If it isn't, he won't waste any time fretting about it. He's not the worrying type, which probably accounts for his relatively youthful appearance. Although he's sixty-nine and the oldest war correspondent in the

Pacific, he looks fifty-five. He learned to fly a

plane when he was fifty-five and to play

tennis when he was sixty. He has been married twice and divorced twice, has a daughter and two sons, both writers who hope to continue the Tarzan series after the old man quits. Tarzan, they realize, is too lucrative a property to abandon.

Burroughs was born in Chicago on September 1, 1875, son of a Civil War major who had made his pile by distilling

alcohol. Trying to cultivate in Edgar a taste for life's finer things, he sent the boy to a private school and even hired a tutor for him, but Edgar showed no appreciable hunger for knowledge. Bundled off to Phillips Academy at Andover,

Massachusetts, he lasted exactly one semester before he left by request.

His father then enrolled him in the Michigan Military Academy at Orchard Lake, Michigan.

After four years there as a cadet, Edgar flunked his entrance exams for West Point. He tried to get a commission int he Chinese Army, but had to settle for a bid from the Nicaraguan Army. He was all for taking a lieutenancy in that mighty outfit, but his parents refused permission. He wound up as a private in the Seventh U. S. Cavalry, chasing bandits along the

Mexican border. He never caught any, and when the Army discovered he had a weak heart, it discharged him He married Me Hulbert in 1900 and went to work for his father in the

storage battery business - for fifteen dollars a week. Since this seemed hardly enough to live on, he went out to Pocatello, Idaho, where his brother Henry backed him in setting up a stationery store. The store failed.

Burroughs then moved on to Oregon, where he worked on a gold dredge, but the company soon went broke. Again his brother came to the rescue, this time getting him a job as a railroad policeman in

Salt Lake City. Chasing bums from boxcars wasn't' particularly remunerative, and Burroughs and his wife soon found themselves almost perpetually hungry. "Neither of us," Burroughs remembers, "Knew much about anything practical. Then a brilliant idea overtook us. We sold our household furniture at an auction. People paid real money for junk, and we went back to Chicago first class.

Chicago, however, treated him just as miserably. Year after year he and his wife remained

poverty-stricken. He sold electric

light bulbs to janitors. He peddled copies of Stoddard's Lectures from door to door. He answered hundreds of want ads, tried accountancy, the mail-order business, even wrote tips on how to become a successful business man. He failed in everything. He began to hate life. Meanwhile, his wife had given birth to Joan and a son christened Hulbert. With the

birth of his second son, Burroughs became desperate.

"I got writer's cramp answering blind ads," he recalls , "and wore out my shoes chasing after others. At last I got placed as an agent for a pencil sharpener. I borrowed office space, and while sub-agents were out trying unsuccessfully to sell the sharpener. I began to write stories."

That was in 1911. In 1912 Tarzan appeared. By 1913, Burroughs was turning out as many as 413,000 words a year at an average rate of three cents a word.

By 1919, grown wealthy, respected as a big-time author, he moved out West and bought 550 acres of ranch land in the San Fernando Valley, fifteen miles north of Hollywood. He named it Tarzana, and when a good portion of it proved unprofitable, he sold it to the exclusive Caballero country club, which promptly failed.

The 1920s were some of his best years. His saddle horses and his private

golf course, his automobiles and children writing two books a year, and managing his properties kept him pleasurably occupied. Tarzan had brought comfort, peace, and riches.

As the years rolled by he took up tennis, bought four cars, motored around the country, then learned to fly. Divorced from his first wife, he eloped by plane to Las Vegas in 1935 and married Florence Gilbert, an actress several years his junior. This marriage lasted until Pearl Harbor caught the Burroughses in Honolulu. Mrs. Burroughs went back to the States and sued for divorce while Burroughs stayed on to cover the war for the United Press and the

Honolulu Advertiser.

He makes his headquarters at the Niumalu Hotel in Honolulu, where he still rises early, knocks out 1,500 or 2,000 words daily and two novels a year, war or no war, while his business manager and sons take care of his interests at the office back in Tarzana. Given a typewriter and an encyclopedia, he feels he will be able to turn out novels indefinitely. He doesn't write any spot news, but he shows up three or four months after the island has been taken, yarns with the men, peps them up, and returns to write feature and human-interest stories, mostly for the Advertiser.

Burroughs plans to stay out in the Pacific for the duration and to continue writing. "For thirty years," he says, tongue in cheek, "I have been writing deathless classics, and I suppose I shall keep on writing them until I am gathered to the bosom of Abraham. In all those years I have not learned one single rule for writing fiction or anything else. I still write as I did thirty years ago; stories which I feel would entertain me and give me mental relaxation, knowing that there are

millions of people just like me who will like the same things that I like."

Evidently there are. THE END

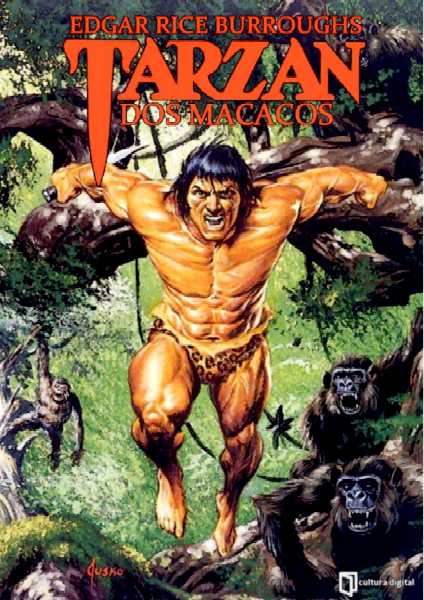

TARZAN

Tarzan is a fictional character, an archetypal feral child raised in the African jungles by the Mangani great apes; he later experiences civilization only to largely reject it and return to the wild as a heroic adventurer. Created by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan first appeared in the novel Tarzan of the

Apes (magazine publication 1912, book publication 1914), and subsequently in twenty-five sequels, three authorized books by other authors, and innumerable works in other

media, both authorized and unauthorized.

TARZAN CHARACTER BIO

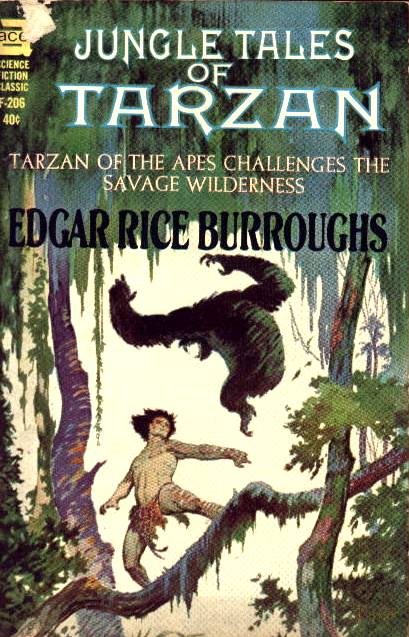

Childhood years

Tarzan is the son of a British lord and lady who were marooned on the Atlantic coast of Africa by mutineers. When Tarzan was only an infant, his mother died of natural causes and his father was killed by Kerchak, leader of the ape tribe by whom Tarzan was adopted. Tarzan's tribe of apes is known as the Mangani, Great Apes of a species unknown to science. Kala is his ape mother. Burroughs added stories occurring during Tarzan's adolescence in his sixth Tarzan book, Jungle Tales of Tarzan. Tarzan is his ape name; his real English name is John Clayton, Viscount Greystoke (according to Burroughs in Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle; Earl of Greystoke in later, less canonical sources, notably the 1984 movie Greystoke). In fact, Burroughs's narrator in Tarzan of the Apes describes both Clayton and Greystoke as fictitious names – implying that, within the fictional world that Tarzan inhabits, he may have a different real name.

Adult life

As a young adult, Tarzan meets a young American woman, Jane Porter. She, her father, and others of their party are marooned on exactly the same coastal jungle area where Tarzan's biological parents were twenty years earlier. When Jane returns to the United States, Tarzan leaves the jungle in search of her, his one true love. In The Return of Tarzan, Tarzan and Jane marry. In later books he lives with her for a time in

England. They have one son, Jack, who takes the ape name Korak ("the Killer"). Tarzan is contemptuous of the hypocrisy of civilization, and he and Jane return to

Africa, making their home on an extensive estate that becomes a base for Tarzan's later adventures.

Characterization

Burroughs created an extreme example of a noble savage figure largely unalloyed with character flaws or faults. He is described as being Caucasian, extremely athletic, tall, handsome, and tanned, with grey eyes and long black hair. Emotionally, he is courageous, intelligent, loyal, and steadfast. He is presented as behaving ethically in most situations, except when seeking vengeance under the motivation of grief, as when his ape mother Kala is killed in Tarzan of the Apes, or when he believes Jane has been

murdered in Tarzan the Untamed. He is deeply in love with his wife and totally devoted to her; in numerous situations where other women express their attraction to him, Tarzan politely but firmly declines their attentions. When presented with a situation where a weaker individual or party is being preyed upon by a stronger foe, Tarzan invariably takes the side of the weaker party. In dealing with other men, Tarzan is firm and forceful. With male friends, he is reserved but deeply loyal and generous. As a host, he is likewise, generous, and gracious. As a leader, he commands devoted loyalty.

In keeping with these noble characteristics, Tarzan's philosophy embraces an extreme form of "return to nature". Although he is able to pass within society as a civilized individual, he prefers to "strip off the thin veneer of civilization", as Burroughs often puts it. His preferred dress is a knife and a loincloth of animal hide, his preferred abode is any convenient tree branch when he desires to sleep, and his favored food is raw meat, killed by himself; even better if he is able to bury it a week so that putrefaction has had a chance to tenderize it a bit.

Tarzan's primitivist philosophy was absorbed by countless fans, amongst whom was Jane Goodall, who describes the Tarzan series as having a major influence on her childhood. She states that she felt she would be a much better spouse for Tarzan than his fictional wife, Jane, and that when she first began to live among and study the chimpanzees she was fulfilling her childhood dream of living among the great apes just as Tarzan did.

Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli has been cited as a major influence on Edgar Rice Burroughs' creation of Tarzan. Mowgli was also an influence for a number of other "wild boy" characters.

Skills and abilities

Tarzan's jungle upbringing gives him abilities far beyond those of ordinary humans. These include climbing, clinging, and leaping as well as any great ape, or better. He uses branches and hanging vines to swing at great speed, a skill acquired among the

anthropoid apes.

His strength, speed, stamina, agility, reflexes, senses, flexibility, durability, endurance, and swimming are extraordinary in comparison to normal men. He has wrestled full grown bull apes and gorillas, lions, rhinos,

crocodiles, pythons, sharks, tigers, man-size seahorses (once) and even dinosaurs (when he visited Pellucidar).

He learns a new language in days, ultimately speaking many languages, including that of the great apes,

French, English, Dutch, German, Swahili, many Bantu dialects, Arabic, ancient

Greek, ancient Latin, Mayan, the languages of the Ant Men and of Pellucidar.

He also communicates with many species of jungle animals.

In Tarzan's Quest (1935), he was one of the recipients of an immortality drug at the end of the book that functionally made him immortal.

TARZAN IN LITERATURE

Tarzan has been called one of the best-known literary characters in the world. In addition to more than two dozen books by Burroughs and a handful more by authors with the blessing of Burroughs' estate, the character has appeared in films,

radio, television, comic strips, and comic books. Numerous parodies and pirated works have also appeared.

Burroughs considered other names for the character, including "Zantar" and "Tublat Zan," before he settled on "Tarzan."

Even though the copyright on Tarzan of the Apes has expired in the United States of America and other countries, the name Tarzan is claimed as a trademark of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

Critical reception

While Tarzan of the Apes met with some critical success, subsequent books in the series received a cooler reception and have been criticized for being derivative and formulaic. The characters are often said to be two-dimensional, the dialogue

wooden, and the storytelling devices (such as excessive reliance on coincidence) strain credulity. According to author

Rudyard Kipling (who himself wrote stories of a feral child, The Jungle Book's Mowgli), Burroughs wrote Tarzan of the Apes just so that he could "find out how bad a book he could write and get away with it."

While Burroughs is not a polished novelist, he is a vivid storyteller, and many of his novels are still in print. In 1963, author Gore Vidal wrote a piece on the Tarzan series that, while pointing out several of the deficiencies that the Tarzan books have as works of literature, praises Edgar Rice Burroughs for creating a compelling "daydream figure". Critical reception grew more positive with the 1981 study by Erling B. Holtsmark, Tarzan and Tradition: Classical Myth in Popular Literature. Holtsmark added a volume on Burroughs for Twayne's

United States Author Series in 1986. In 2010, Stan Galloway provided a sustained study of the adolescent period of the fictional Tarzan's life in The Teenage Tarzan.

Despite critical panning, the Tarzan stories have remained popular. Burroughs's melodramatic situations and the elaborate details he works into his fictional world, such as his construction of a partial language for his great apes, appeal to a worldwide fan base.

TARZAN

NOVELS

Tarzan of the Apes (1912)

The Return of Tarzan (1913)

The Beasts of Tarzan (1914)

The Son of Tarzan (1914)

Tarzan and the Jewels of Opar (1916)

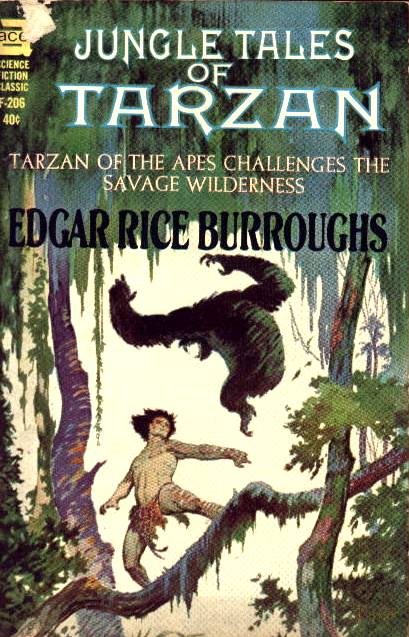

Jungle Tales of Tarzan, 1917 [1916].

Tarzan the Untamed, 1921 [1919].

Tarzan the Terrible (1921)

Tarzan and the Golden Lion, 1923 [1922].

Tarzan and the Ant Men (1924)

Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, 1928 [1927].

Tarzan and the Lost Empire (1928)

Tarzan at the Earth's Core (1929)

Tarzan the Invincible (1930–31).

Tarzan Triumphant (1931)

Tarzan and the City of Gold (1932)

Tarzan and the Lion Man, 1934 [1933].

Tarzan and the Leopard Men (1935)

Tarzan's Quest, 1936 [1935].

Tarzan the Magnificent, 1937 [1936].

Tarzan and the Forbidden City (1938)

Tarzan and the Foreign Legion (1947)

Tarzan and the Tarzan Twins (1963, for younger readers)

Tarzan and the Madman (1964)

Tarzan and the Castaways (1965)

Burroughs, Edgar Rice; Lansdale, Joe R (1995), Tarzan: the Lost Adventure.

TARZAN FILMS

The Internet Movie Database lists 200 movies with Tarzan in the title between 1918 and 2014. The first Tarzan movies were silent pictures adapted from the original Tarzan novels, which appeared within a few years of the character's creation. The first actor to portray the adult Tarzan was Elmo Lincoln in 1918's Tarzan Of The Apes. With the advent of talking pictures, a popular Tarzan movie franchise was developed, which lasted from the 1930s through the 1960s. Starting with Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932 through twelve films until 1948, the franchise was anchored by former

Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller in the title role. Weissmuller and his immediate successors were enjoined to portray the ape-man as a noble savage speaking broken English, in marked contrast to the cultured aristocrat of Burroughs's novels.

With the exception of the Burroughs co-produced The New Adventures of Tarzan, this "me Tarzan, you Jane" characterization of Tarzan persisted until the late 1950s, when producer Sy Weintraub, having bought the film rights from producer Sol Lesser, produced Tarzan's Greatest Adventure followed by eight other films and a television series. The Weintraub productions portray a Tarzan that is closer to Edgar Rice Burroughs' original concept in the novels: a jungle lord who speaks grammatical English and is well educated and familiar with civilization. Most Tarzan films made before the mid-fifties were black-and-white films shot on studio sets, with stock jungle footage edited in. The Weintraub productions from 1959 on were shot in foreign locations and were in color.

There were also several serials and features that competed with the main franchise, including Tarzan the Fearless (1933) starring Buster Crabbe and The New Adventures of Tarzan (1935) starring Herman Brix. The latter serial was unique for its period in that it was partially filmed on location (Guatemala) and portrayed Tarzan as educated. It was the only Tarzan film project for which Edgar Rice Burroughs was personally involved in the production.

Tarzan films from the 1930s on often featured Tarzan's chimpanzee companion Cheeta, his consort Jane (not usually given a last name), and an adopted son, usually known only as "Boy." The Weintraub productions from 1959 on dropped the character of Jane and portrayed Tarzan as a lone adventurer. Later Tarzan films have been occasional and somewhat idiosyncratic. Recently, Tony Goldwyn portrayed Tarzan in Disney’s animated film of the same name (1999). This version marked a new beginning for the ape man, taking its inspiration equally from Burroughs and the 1984 film Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes.

TARZAN TV

Television later emerged as a primary vehicle bringing the character to the public. From the mid-1950s, all the extant sound Tarzan films became staples of Saturday morning television aimed at young and teenaged viewers. In 1958, movie Tarzan Gordon Scott filmed three episodes for a prospective television series. The program did not sell, but a different live action Tarzan series produced by Sy Weintraub and starring Ron Ely ran on

NBC from 1966 to 1968. An animated series from Filmation, Tarzan, Lord of the

Jungle, aired from 1976 to 1977, followed by the anthology programs Batman/Tarzan Adventure Hour (1977–1978), Tarzan and the Super 7 (1978–1980), The Tarzan/Lone Ranger Adventure Hour (1980–1981), and The Tarzan/Lone Ranger/Zorro Adventure Hour) (1981–1982). Joe Lara starred in the title role in Tarzan in Manhattan (1989), an offbeat TV movie, and later returned in a completely different interpretation in Tarzan: The Epic Adventures (1996), a new live-action series. In between the two productions with Lara, Tarzán, a half-hour syndicated series ran from 1991 through 1994. In this version of the show, Tarzan was portrayed as a blond environmentalist, with Jane turned into a French ecologist. Disney’s animated series The Legend of Tarzan (2001–2003) was a spin-off from its animated film. The latest television series was the live-action Tarzan (2003), which starred male model Travis Fimmel and updated the setting to contemporary New York City, with Jane as a police detective, played by Sarah Wayne Callies. The series was cancelled after only eight episodes. A 1981 television special, The Muppets Go to the Movies, features a short sketch titled "Tarzan and Jane". Lily Tomlin plays Jane opposite The Great Gonzo as Tarzan. In addition, the Muppets have made reference to Tarzan on half a dozen occasions since the 1960s. Saturday Night Live featured recurring sketches with the speech-impaired trio of "Frankenstein, Tonto, and Tarzan".

Television later emerged as a primary vehicle bringing the character to the public. From the mid-1950s, all the extant sound Tarzan films became staples of Saturday morning television aimed at young and teenaged viewers. In 1958, movie Tarzan Gordon Scott filmed three episodes for a prospective television series. The program did not sell, but a different live action Tarzan series produced by Sy Weintraub and starring Ron Ely ran on NBC from 1966 to 1968. An animated series from Filmation, Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle, aired from 1976 to 1977, followed by the anthology programs Batman/Tarzan Adventure Hour (1977–1978), Tarzan and the Super 7 (1978–1980), The Tarzan/Lone Ranger Adventure Hour (1980–1981), and The Tarzan/Lone Ranger/Zorro Adventure Hour) (1981–1982). Joe Lara starred in the title role in Tarzan in Manhattan (1989), an offbeat TV movie, and later returned in a completely different interpretation in Tarzan: The Epic Adventures (1996), a new live-action series. In between the two productions with Lara, Tarzán, a half-hour syndicated series ran from 1991 through 1994. In this version of the show, Tarzan was portrayed as a blond environmentalist, with Jane turned into a

French ecologist. Disney’s animated series The Legend of Tarzan (2001–2003) was a spin-off from its animated film. The latest television series was the live-action Tarzan (2003), which starred male model Travis Fimmel and updated the setting to contemporary New York City, with Jane as a police detective, played by Sarah Wayne Callies. The series was cancelled after only eight episodes. A 1981 television special, The Muppets Go to the Movies, features a short sketch titled "Tarzan and Jane". Lily Tomlin plays Jane opposite The Great Gonzo as Tarzan. In addition, the Muppets have made reference to Tarzan on half a dozen occasions since the 1960s. Saturday Night Live featured recurring sketches with the speech-impaired trio of "Frankenstein, Tonto, and Tarzan".

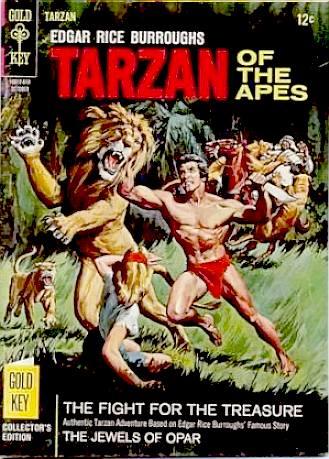

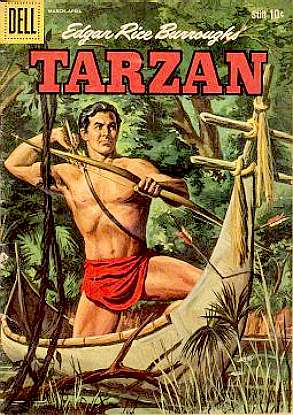

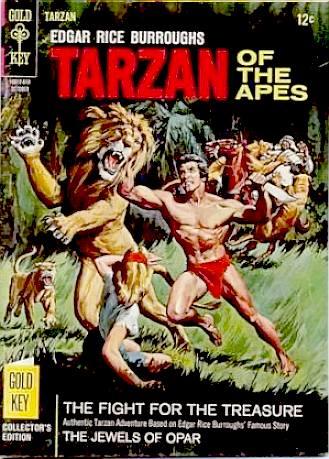

TARZAN GRAPHIC NOVELS (COMICS)

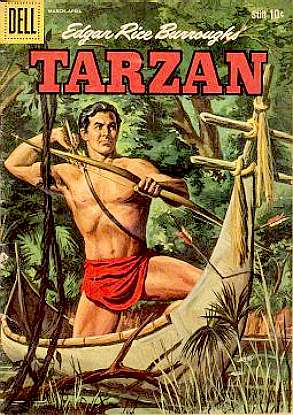

Tarzan of the Apes was adapted in newspaper strip form, in early 1929, with illustrations by Hal Foster. A full page Sunday strip began March 15, 1931 by Rex Maxon. Over the years, many artists have drawn the Tarzan comic strip, notably Burne Hogarth, Russ Manning, and Mike Grell. The daily strip began to reprint old dailies after the last Russ Manning daily (#10,308, which ran on 29 July 1972). The Sunday strip also turned to reprints circa 2000. Both strips continue as reprints today in a few newspapers and in Comics Revue magazine. NBM Publishing did a high quality reprint series of the Foster and Hogarth work on Tarzan in a series of hardback and paperback reprints in the 1990s.

Tarzan has appeared in many comic books from numerous publishers over the years. The character's earliest comic book appearances were in comic strip reprints published in several titles, such as Sparkler, Tip Top Comics and Single Series. Western Publishing published Tarzan in Dell Comics's Four Color Comics #134 & 161 in 1947, before giving him his own series, Tarzan, published through Dell Comics and later Gold Key Comics from January–February 1948 to February 1972). DC took over the series in 1972, publishing Tarzan #207-258 from April 1972 to February 1977, including work by Joe Kubert. In 1977 the series moved to

Marvel Comics, which restarted the numbering rather than assuming that used by the previous publishers. Marvel issued Tarzan #1-29 (as well as three Annuals), from June 1977 to October 1979, mainly by John Buscema. Following the conclusion of the Marvel series the character had no regular comic book publisher for a number of years. During this period Blackthorne Comics published Tarzan in 1986, and Malibu Comics published Tarzan comics in 1992. Dark Horse Comics has published various Tarzan series from 1996 to the present, including reprints of works from previous publishers like Gold Key and DC, and joint projects with other publishers featuring crossovers with other characters.

There have also been a number of different comic book projects from other publishers over the years, in addition to various minor appearances of Tarzan in other comic books. The

Japanese manga series Jungle no Ouja Ta-chan (Jungle King Tar-chan) by Tokuhiro Masaya was based loosely on Tarzan. Also, manga "god" Osamu Tezuka created a Tarzan manga in 1948 entitled Tarzan no Himitsu Kichi (Tarzan's Secret Base).

A

real life Tarzan, a practical

pioneering woodsman who loves climbing

trees, cliffs and even buildings. Nelson is seen here removing a

weed sycamore tree from the grounds of Herstmonceux Science Museum in

September 2014.

ERB

LINKS & REFERENCE

Classic

Cinema Gold Edgar Rice Burroughs

Encyclopedia

Britannica

Edgar-Rice-Burroughs

Wikipedia

Tarzan

Wikipedia

Edgar_Rice_Burroughs

Edgar

Rice Burroughs

http://classiccinemagold.com/tag/edgar-rice-burroughs/

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/85800/Edgar-Rice-Burroughs

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarzan

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Rice_Burroughs

http://www.edgarriceburroughs.com/

http://www.tarzan.org/

http://www.tarzan.com/

http://www.erbzine.com/mag31/3159.html

http://www.literature.org/authors/burroughs-edgar-rice/

Tarzan.com

Tarzan.org

ERBzine.com

How-popular-were-edgar-rice-burroughs-novels-think-harry-potter-and-then-some

Erbzine

magazine Edgar Rice Burroughs

Literature

Burroughs, Edgar Rice

Edgar

Rice Burroughs at find a grave

NOVELIST

INDEX

A - Z

|