|

Pictures of

the toads on this page were taken at Herstmonceux in East

Sussex, England. The ponds that these magnificent creatures use

to spawn, are under threat from developers, in the rush to make

money over conservation of

species. It is hoped they might be

protected, even though they are a species not considered in

danger of extinction.

The common toad, European toad, or in Anglophone parts of Europe, simply the toad (Bufo bufo, from Latin bufo "toad"), is a toad found throughout most of Europe (with the exception of Ireland,

Iceland, parts of Scandinavia, and some Mediterranean islands), in the western part of North

Asia, and in a small portion of Northwest

Africa. It is one of a group of closely related animals that are descended from a common ancestral line of toads and which form a species complex. The toad is an inconspicuous animal as it usually lies hidden during the day. It becomes active at dusk and spends the night hunting for the invertebrates on which it feeds. It moves with a slow, ungainly walk or short jumps, and has greyish-brown skin covered with wart-like lumps.

Although toads are usually solitary animals, in the breeding season, large numbers of toads converge on certain breeding ponds, where the males compete to mate with the females. Eggs are laid in gelatinous strings in the water and later hatch out into tadpoles. After several months of growth and development, these sprout limbs and undergo metamorphosis into tiny toads. The juveniles emerge from the water and remain largely terrestrial for the rest of their lives.

Without a pond or other slow moving stream, toads and frogs

would cease to have their incubation mechanism.

The common toad seems to be in decline in part of its range, but overall is listed as being of "least concern" in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is threatened by habitat loss, especially by drainage of its breeding sites, and some toads get killed on the roads as they make their annual migrations. It has long been associated in popular culture and literature with witchcraft.

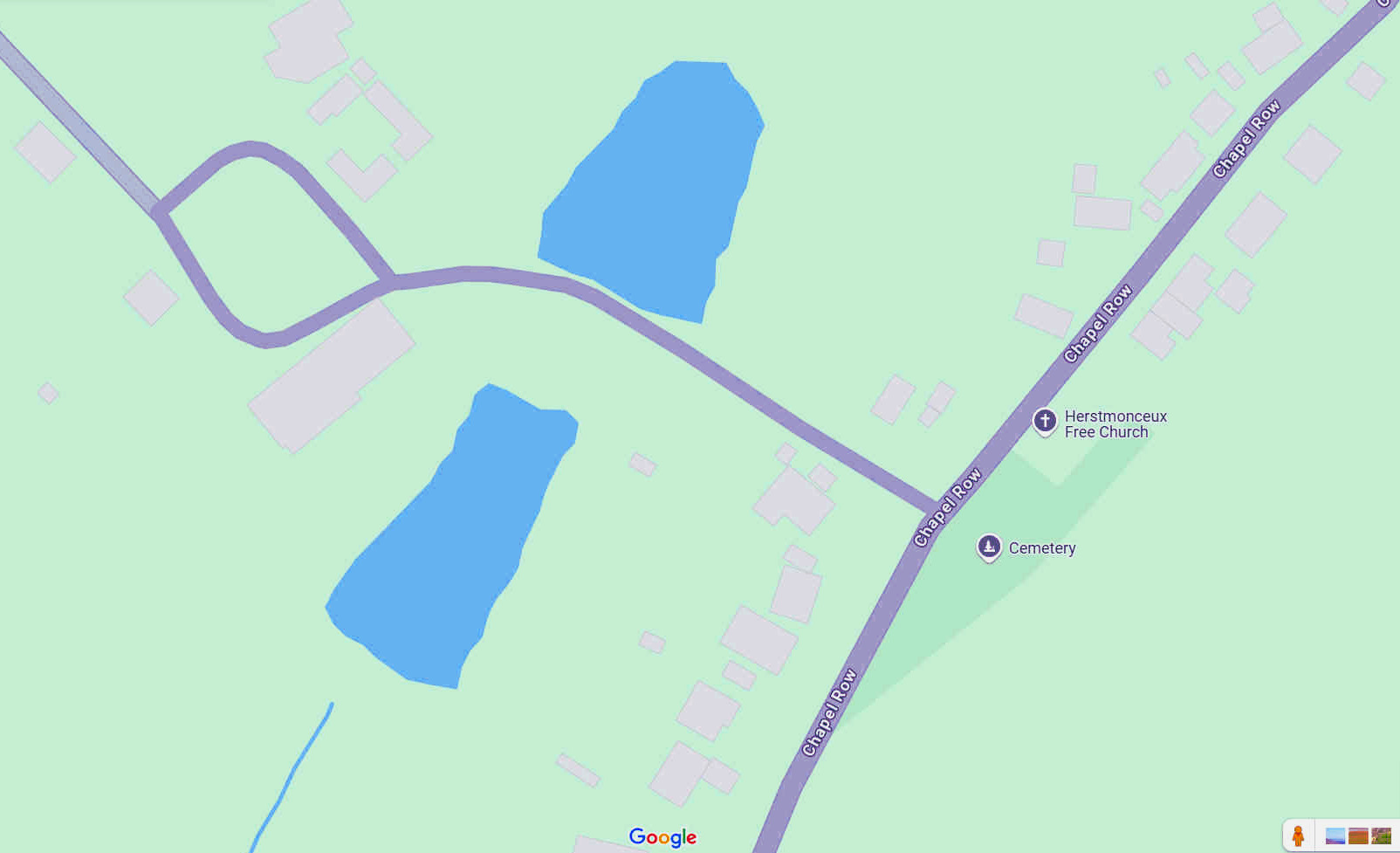

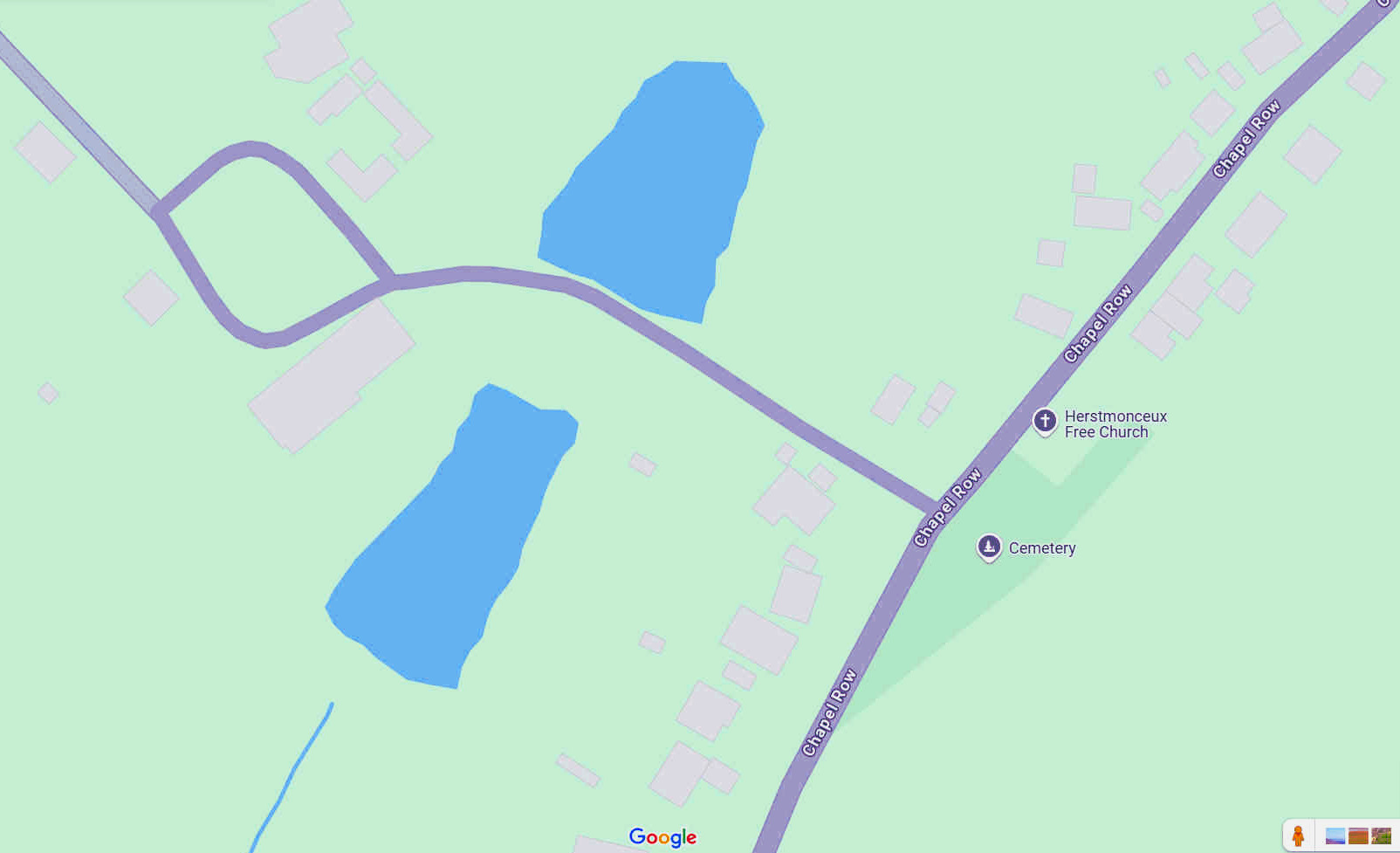

Ponds are

frequently endangered by developers of housing estates, as is

this one near Herstmonceux

in East

Sussex, England. In this case, Latimer Homes and the Clarion

Housing group are proposing drainage that is sure to dry out the

ponds and cause major upset to the wildlife in this location

that depends on the water from adjacent fields to survive. This

is a whole ecosystem, including ducks, toads, fish, herons, and

great crested newts. The houses are more over development of

executive homes for renting landlords, where in the UK there is

an acute shortage of genuinely affordable housing, so

perpetuating the rent trap that young families cannot escape in

their lifetime. The A271

is already overloaded with traffic that routinely causes

dangerous potholes in the village high street every year. And

the proposed access is so dangerous that it has been named

locally: Suicide

Junction. It is unclear if the local farmer at Lime End Farm

is agreeable to the proposal, or if the local Wealden

District Council will be exercising their compulsory

purchase powers. The initial application in 2015 came as a shock

to local residents, with over 300 people attending the village

hall to object to yet more inappropriate local development. In

addition, the location is home to the only electricity

generating station in the world, featuring battery load

levelling from C. 1896. Hence, a potential UNESCO

world

heritage site.

This network of ponds has been sustained for over 40 years by surface water runoff from the adjacent field. This established flow of water has become a prescriptive right under the Prescription Act 1832, meaning that the continued flow of water cannot be legally obstructed after such a long period of uninterrupted use.

Diverting this water source will have a devastating impact on the ponds, likely leading to their desiccation and the destruction of the established ecosystem.

Critically, the pond network is an integral part of the setting of

the unique local heritage asset: the only surviving early electricity generating station

in Europe. This building is a significant historical landmark, and its setting, including the ponds and surrounding landscape, contributes significantly to its historical and architectural significance. The rural setting and surrounding countryside are part of the charm of the technology that nestles in this estate, as a time capsule. This historical and environmental context may well be protected by other conservation law, and that is now under threat. The proposed

land drainage diversion would severely compromise this historical setting and diminish the heritage value of the site.

DESCRIPTION

The common toad can reach about 15 cm (6 in) in length. Females are normally stouter than males and southern specimens tend to be larger than northern ones. The head is broad with a wide mouth below the terminal snout which has two small nostrils. There are no teeth. The bulbous, protruding eyes have yellow or copper coloured irises and horizontal slit-shaped pupils. Just behind the eyes are two bulging regions, the paratoid glands, which are positioned obliquely. They contain a noxious substance, bufotoxin, which is used to deter potential predators. The head joins the body without a noticeable neck and there is no external vocal sac. The body is broad and squat and positioned close to the ground. The fore limbs are short with the toes of the fore feet turning inwards. At breeding time, the male develops nuptial pads on the first three fingers. He uses these to grasp the female when mating. The hind legs are short relative to other frogs' legs and the hind feet have long, unwebbed toes. There is no tail. The skin is dry and covered with small wart-like lumps. The colour is a fairly uniform shade of brown, olive-brown or greyish-brown, sometimes partly blotched or banded with a darker shade. The common toad tends to be sexually dimorphic with the females being browner and the males greyer. The underside is a dirty white speckled with grey and black patches.

Other species with which the common toad could be confused include the natterjack toad (Bufo calamita) and the European green toad (Bufo viridis). The former is usually smaller and has a yellow band running down its back while the latter has a distinctive mottled pattern. The paratoid glands of both are parallel rather than slanting as in the common toad. The common frog (Rana temporaria) is also similar in appearance but it has a less rounded snout, damp smooth skin, and usually moves by leaping.

Common toads can live for many years and have survived for fifty years in captivity. In the wild, common toads are thought to live for about ten to twelve years. Their age can be determined by counting the number of annual growth rings in the bones of their phalanges.

HABITAT

After the common frog (Rana temporaria), the edible frog (Pelophylax esculentus) and the smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris), the common toad is the fourth most common amphibian in Europe. It is found throughout the continent with the exception of Iceland, the cold northern parts of

Scandinavia, Ireland and a number of

Mediterranean islands. These include

Malta, Crete, Corsica, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands. Its easterly range extends to Irkutsk in Siberia and its southerly range includes parts of northwestern Africa in the northern mountain ranges of

Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. A closely related variant lives in eastern Asia including

Japan. The common toad is found at altitudes of up to 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) in the southern part of its range. It is largely found in forested areas with coniferous, deciduous and mixed woodland, especially in wet locations. It also inhabits open countryside, fields, copses, parks and gardens, and often occurs in dry areas well away from standing water.

CONSERVATION

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species considers the common toad as being of "least concern". This is because it has a wide distribution and is, over most of its range, a common species. It is not particularly threatened by habitat loss because it is adaptable and is found in deciduous and coniferous

forests, scrubland, meadows, parks and gardens. It prefers damp areas with dense foliage. The major threats it faces include loss of habitat locally, the drainage of wetlands where it breeds, agricultural activities, pollution, and mortality on roads. Chytridiomycosis, an infectious disease of amphibians, has been reported in common toads in Spain and the

United Kingdom and may affect some populations.

There are parts of its range where the common toad seems to be in decline. In

Spain, increased aridity and habitat loss have led to a diminution in numbers and it is regarded as "near threatened". A population in the Sierra de Gredos mountain range is facing predation by otters and increased competition from the frog Pelophylax perezi. Both otter and frog seem to be extending their ranges to higher altitudes. The common toad cannot be legally sold or traded in the United Kingdom but there is a slow decline in toad numbers and it has therefore been declared a Biodiversity Action Plan priority species. In Russia, it is considered to be a "Rare Species" in the Bashkortostan Republic, the Tatarstan Republic, the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and the Irkutsk Oblast, but during the 1990s, it became more abundant in

Moscow Oblast.

It has been found that urban populations of common toad occupying small areas and isolated by development show a lower level of genetic diversity and reduced fitness as compared to nearby rural populations. The researchers demonstrated this by genetic analysis and by noting the greater number of physical abnormalities among urban as against rural tadpoles when raised in a controlled environment. It was considered that long term depletion in numbers and habitat fragmentation can reduce population persistence in such urban environments.

ROADKILL

Many toads are killed by traffic while migrating to their breeding grounds. In

Europe they have the highest rate of mortality from roadkill among amphibians. Many of the deaths take place on stretches of road where streams flow underneath showing that migration routes often follow water

courses. In some places in Germany,

Belgium, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Northern

Italy and Poland, special tunnels have been constructed so that toads can cross under roads in safety. In other places, local wildlife groups run "toad patrols", carrying the amphibians across roads at busy crossing points in buckets. The toads start moving at dusk and for them to travel far, the temperature needs to remain above 5 °C (41 °F). On a warm wet night they may continue moving all night but if it cools down, they may stop earlier. An estimate was made of the significance of roadkill in toad populations in the

Netherlands. The number of females killed in the spring migration on a quiet country road (ten vehicles per hour) was compared with the number of strings of eggs laid in nearby fens. A 30% mortality rate was found, with the rate for deaths among males likely to be of a similar order.

AMPHIBIAN

CONSERVATION

Dramatic declines in amphibian populations, including population crashes and mass localized extinction, have been noted since the late 1980s from locations all over the world, and amphibian declines are thus perceived to be one of the most critical threats to global biodiversity. In 2004, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reported stating that currently birds, mammals, and amphibians extinction rates were at minimum 48 times greater than natural extinction rates

- possibly 1,024 times higher. In 2006, there were believed to be 4,035 species of amphibians that depended on water at some stage during their life cycle. Of these, 1,356 (33.6%) were considered to be threatened and this figure is likely to be an underestimate because it excludes 1,427 species for which there was insufficient data to assess their status. A number of causes are believed to be involved, including habitat destruction and modification, over-exploitation, pollution, introduced species, global warming, endocrine-disrupting pollutants, destruction of the ozone layer (ultraviolet radiation has shown to be especially damaging to the skin, eyes, and eggs of amphibians), and diseases like chytridiomycosis. However, many of the causes of amphibian declines are still poorly understood, and are a topic of ongoing discussion.

POLLUTION AND PESTICIDES

The decline in amphibian and reptile populations has led to an awareness of the effects of pesticides on reptiles and amphibians. In the past, the argument that amphibians or reptiles were more susceptible to any chemical contamination than any land aquatic vertebrate was not supported by research until recently. Amphibians and reptiles have complex life cycles, live in different climate and ecological zones, and are more vulnerable to chemical exposure. Certain pesticides, such as organophosphates, neonicotinoids, and carbamates, react via cholinesterase inhibition. Cholinesterase is an enzyme that causes the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, an excitatory neurotransmitter that is abundant in the nervous system. AChE inhibitors are either reversible or irreversible, and carbamates are safer than organophosphorus insecticides, which are more likely to cause cholinergic poisoning. Reptile exposure to an AChE inhibitory pesticide may result in disruption of neural function in reptiles. The buildup of these inhibitory effects on motor performance, such as food consumption and other activities.

PROTECTION STRATEGIES

The Amphibian Specialist Group of the IUCN is spearheading efforts to implement a comprehensive global strategy for amphibian conservation. Amphibian

Ark is an organization that was formed to implement the ex-situ conservation recommendations of this plan, and they have been working with zoos and aquaria around the world, encouraging them to create assurance colonies of threatened amphibians. One such project is the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project that built on existing conservation efforts in

Panama to create a country-wide response to the threat of chytridiomycosis.

Another measure would be to stop exploitation of frogs for human consumption. In the Middle East, a growing appetite for eating frog legs and the consequent gathering of them for food was already linked to an increase in mosquitoes and thus has direct consequences for

human health.

Please

use the Index below to navigate the Animal Kingdom:-

|

AMPHIBIANS |

Such

as frogs (class: Amphibia), Newts,

Toads |

|

ANNELIDS |

As

in Earthworms (phyla: Annelida) |

|

ANTHROPOLOGY |

Neanderthals,

Homo Erectus (Extinct) |

|

ARACHNIDS |

Spiders

(class: Arachnida) |

|

BIRDS

|

Such

as Eagles, Albatross

(class: Aves) |

|

CETACEANS

|

such

as Whales

& Dolphins

( order:Cetacea) |

|

CRUSTACEANS |

such

as crabs (subphyla: Crustacea) |

|

DINOSAURS

|

Tyranosaurus

Rex,

Brontosaurus (Extinct) |

|

ECHINODERMS |

As

in Starfish (phyla: Echinodermata) |

|

FISH

|

Sharks,

Tuna (group: Pisces) |

|

HUMANS

-

MAN |

Homo

Sapiens THE

BRAIN |

|

INSECTS |

Ants,

(subphyla: Uniramia class:

Insecta) |

|

LIFE

ON EARTH

|

Which

includes PLANTS

non- animal life |

|

MAMMALS

|

Warm

blooded animals (class: Mammalia) |

|

MARSUPIALS |

Such

as Kangaroos

(order: Marsupialia) |

|

MOLLUSKS |

Such

as octopus (phyla: Mollusca) |

|

PLANTS |

Trees

- |

|

PRIMATES |

Gorillas,

Chimpanzees

(order: Primates) |

|

REPTILES |

As

in Crocodiles,

Snakes (class: Reptilia) |

|

RODENTS |

such

as Rats, Mice (order: Rodentia) |

|

SIMPLE

LIFE FORMS

|

As

in Amoeba, plankton (phyla: protozoa) |

|

|

It's

sad to think that one day, the planet Earth may be gone.

This is despite our best efforts to save her. The good news is

that provided we all work together, we can preserve the status

quo on our beautiful blue

planet, for centuries to come.

Provided that is we heed the warnings nature is sending us, such

as global warming and other pollutions.

|