|

The northern crested newt, great crested newt or warty newt (Triturus cristatus) is a newt species native to

Great

Britain, northern and central continental Europe and parts of Western Siberia. It is a large newt, with females growing up to 16 cm (6.3 in) long. Its back and sides are dark brown, while the belly is yellow to orange with dark blotches. Males develop a conspicuous jagged crest on their back and tail during the breeding season.

The northern crested newt spends most of the year on land, mainly in forested areas in lowlands. It moves to aquatic breeding sites, mainly larger fish-free ponds, in spring. Males court females with a ritualised display and deposit a spermatophore on the ground, which the female then picks up with her cloaca. After fertilisation, a female lays around 200 eggs, folding them into water plants. The larvae develop over two to four months before metamorphosing into terrestrial juveniles (efts). Both larvae and land-dwelling newts mainly feed on different invertebrates.

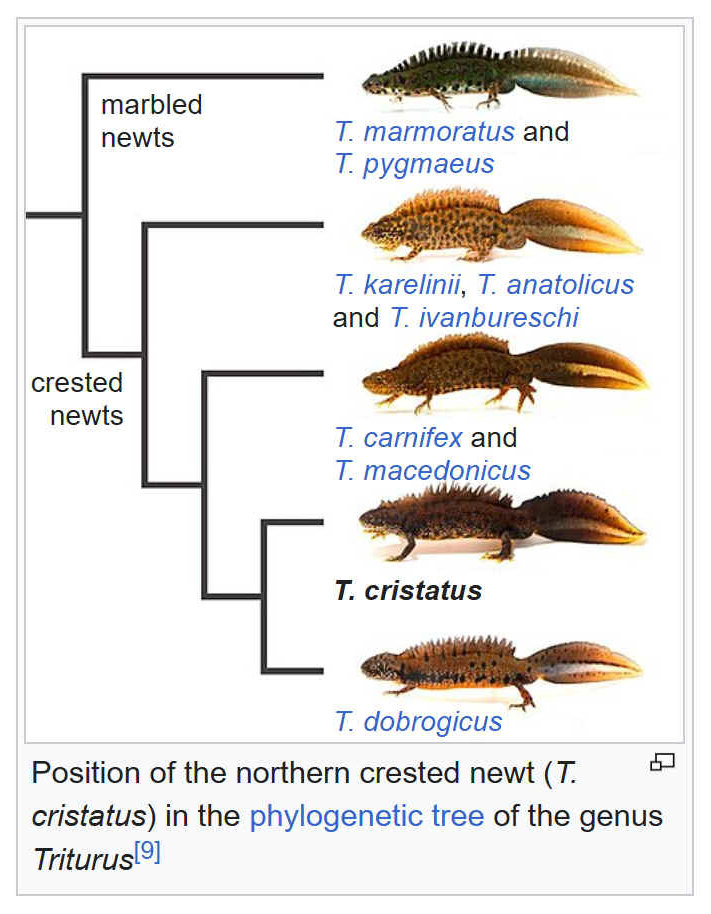

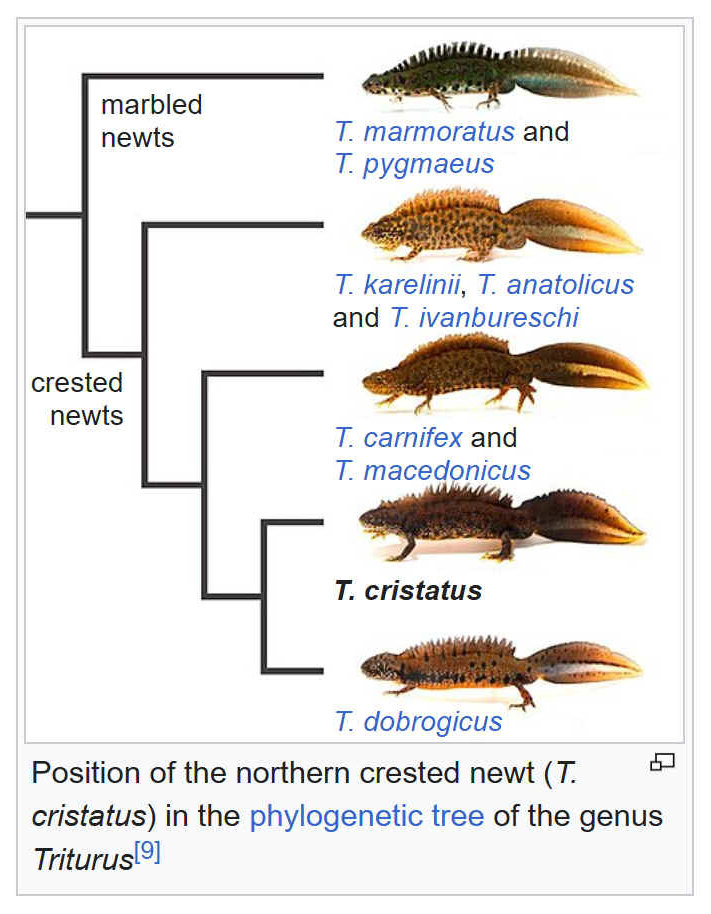

Several of the northern crested newt's former subspecies are now recognised as separate species in the genus Triturus. Its closest relative is the Danube crested newt (T. dobrogicus). It sometimes forms hybrids with some of its relatives, including the marbled newt (T. marmoratus). Although today the most widespread Triturus species, the northern crested newt was probably confined to small refugial areas in the Carpathians during the Last Glacial Maximum.

While the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists it as Least Concern species, populations of the northern crested newt have been declining. The main threat is habitat destruction, for example, through urban sprawl. The species is listed as a European Protected Species.

WHAT THEY LOOK LIKE

The northern crested newt is a relatively large newt species. Males usually reach 13.5 cm (5.3 in) total length, while females grow up to 16 cm (6.3 in). Rare individuals of 20 cm (7.9 in) have been recorded. Other crested newt species are more stockily built; only the Danube crested newt (T. dobrogicus) is more slender. Body shape is correlated with skeletal build: The northern crested newt has 15 rib-bearing vertebrae, only the Danube crested newt has more (16–17), while the other, more stocky Triturus species have 14 or less.

The newts have rough skin, and are dark brown on the back and sides, with black spots and heavy white stippling on the flanks. The female has a yellow line running along the lower tail edge. The throat is mixed yellow–black with fine white stippling, the belly yellow to orange with dark, irregular blotches.

During the aquatic breeding season, males develop crest up to 1.5 cm (0.59 in) high, which runs along the back and tail but is interrupted at the tail base. It is heavily indented on the back but smoother on the tail. Also during breeding season, the male's cloaca swells and it has a blue–white flash running along the sides of the tail. Females do not develop a crest.

In certain areas of France, the northern crested newt and the marbled newt overlap, and hybrids are present. As the northern crested newt's population grows, and marbled newt population struggles, these hybrids have been shown to possess good qualities of both. They have more fecundity than the two newts however have a hard time keeping their eggs alive.

SPREAD

The northern crested newt is the most widespread and northerly crested newt species. The northern edge of its range runs from Great Britain through southern Fennoscandia to the Republic of Karelia in

Russia; the southern margin runs through central France, southwest Romania, Moldavia and Ukraine, heading from there into central Russia and through the Ural Mountains. The eastern extent of the great crested newt's range reaches into Western Siberia, running from the Perm Krai to the Kurgan Oblast.

In western France, the species co-occurs and sometimes hybridises (see section Evolution below) with the marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus). In southeast Europe, its range borders that of the Italian crested newt (T. carnifex), the Danube crested newt (T. dobrogicus), the Macedonian crested newt (T. macedonicus) and the Balkan crested newt (T. ivanbureschi).

HABITAT

Outside of the breeding season, northern crested newts are mainly forest-dwellers. They prefer deciduous woodlands or groves, but conifer woods are also accepted, especially in the far northern and southern ranges. In the absence of forests, other cover-rich habitats, as for example hedgerows, scrub, swampy meadows, or quarries, can be inhabited.

Preferred aquatic breeding sites are stagnant, mid- to large-sized, unshaded water bodies with abundant underwater vegetation but without fish (which prey on larvae). Typical examples are larger ponds, which need not be of natural origin; indeed, most ponds inhabited in the United Kingdom are human-made. Examples of other suitable secondary habitats are ditches, channels, gravel pit lakes, or garden ponds. Other newts that can sometimes be found in the same breeding sites are the smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris), the palmate newt (L. helveticus), the Carpathian newt (L. montadoni), the alpine newt (Ichthyosaura alpestris) and the marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus).

The northern crested newt is generally a lowland species but has been found up to 1,750 m (5,740 ft) in the Alps.

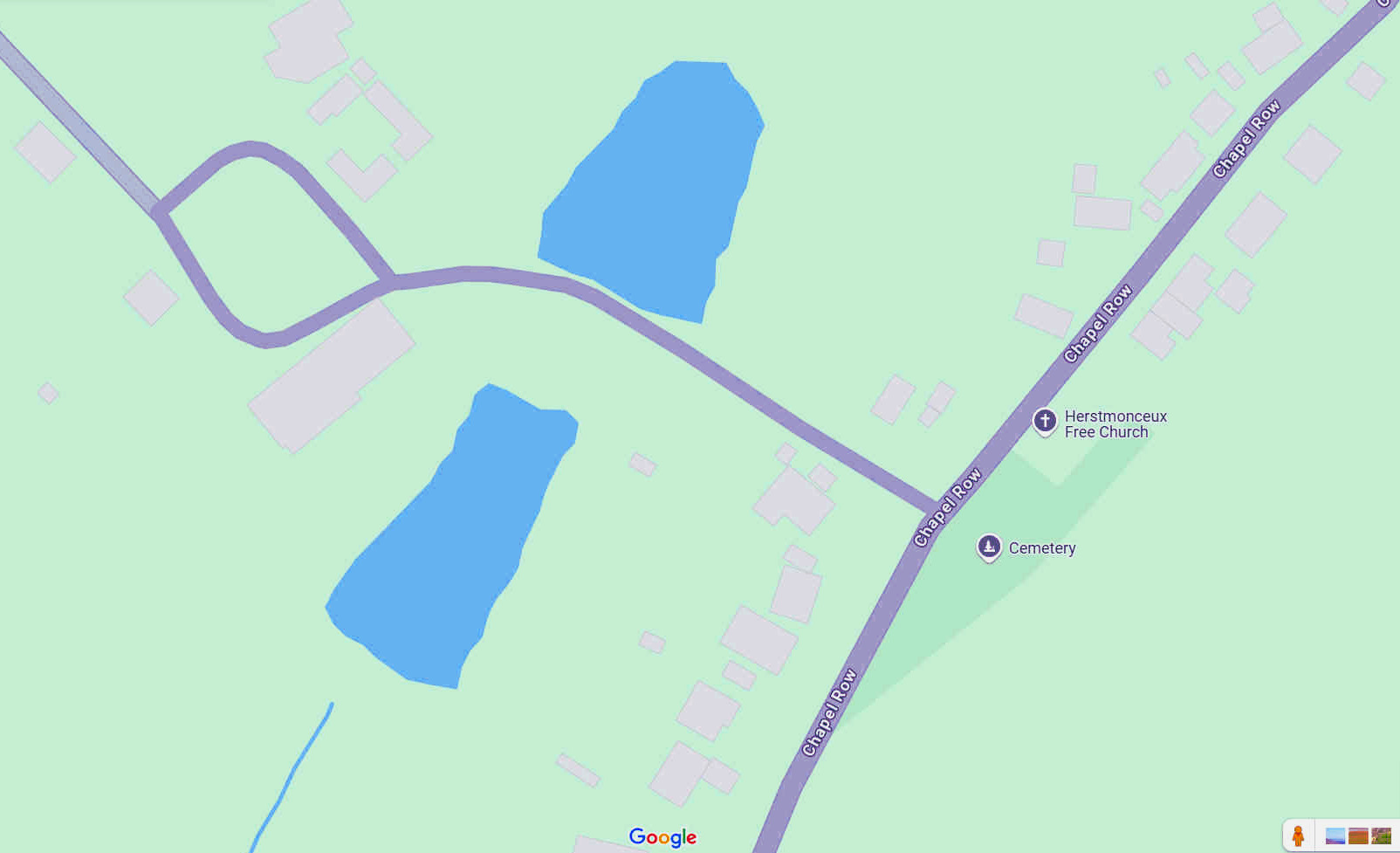

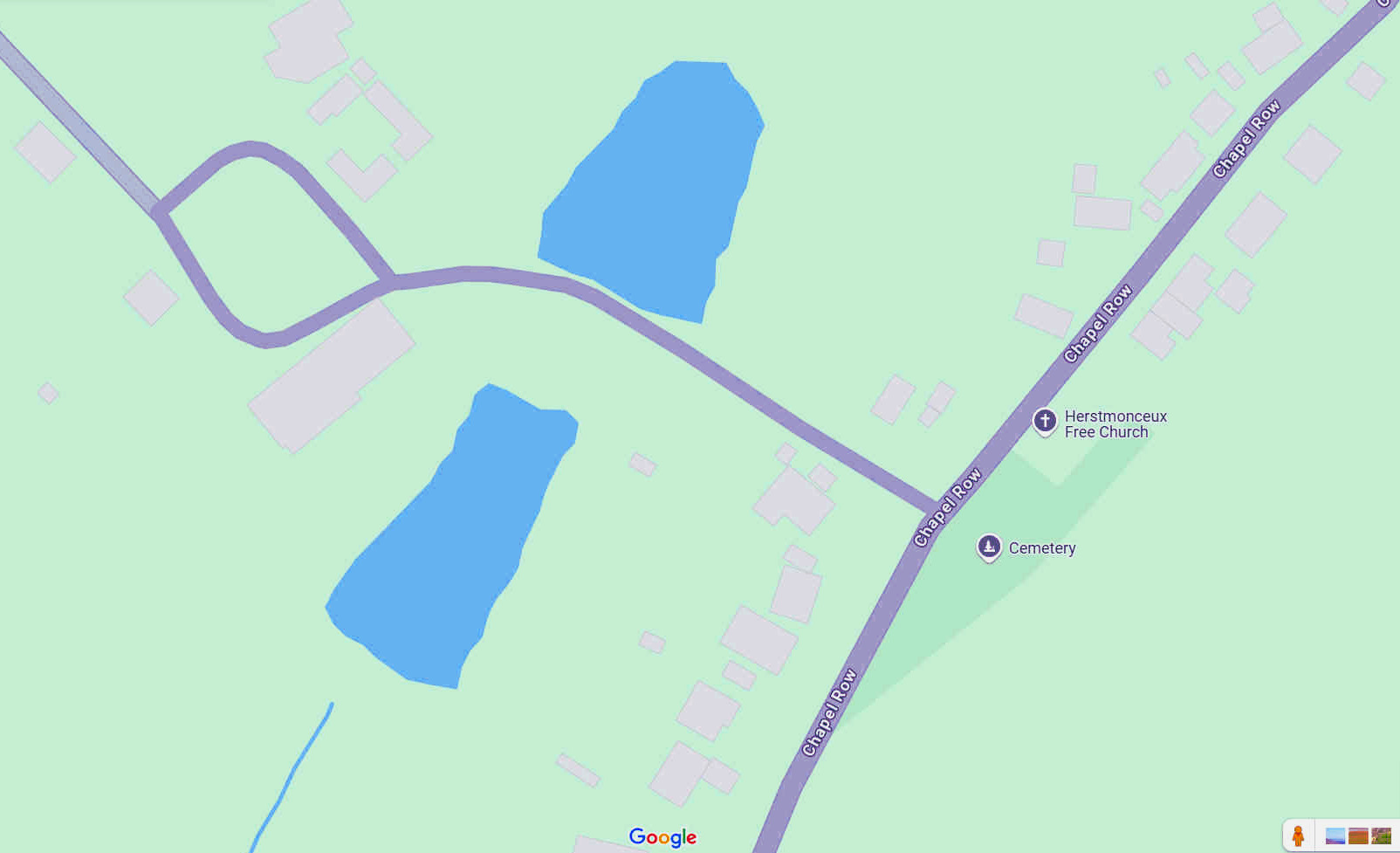

Ponds are

frequently endangered by developers of housing estates, as is

this one near Herstmonceux

in East

Sussex, England. In this case, Latimer Homes and the Clarion

Housing group are proposing drainage that is sure to dry out the

ponds and cause major upset to the wildlife in this location

that depends on the water from adjacent fields to survive. This

is a whole ecosystem, including ducks, toads, fish, herons, and

great crested newts. The houses are more over development of

executive homes for renting landlords, where in the UK there is

an acute shortage of genuinely affordable housing, so

perpetuating the rent trap that young families cannot escape in

their lifetime. The A271

is already overloaded with traffic that routinely causes

dangerous potholes in the village high street every year. And

the proposed access is so dangerous that it has been named

locally: Suicide

Junction. It is unclear if the local farmer at Lime End Farm

is agreeable to the proposal, or if the local Wealden

District Council will be exercising their compulsory

purchase powers. The initial application in 2015 came as a shock

to local residents, with over 300 people attending the village

hall to object to yet more inappropriate local development. In

addition, the location is home to the only electricity

generating station in the world, featuring battery load

levelling from C. 1896. Hence, a potential UNESCO

world

heritage site.

This network of ponds has been sustained for over 40 years by surface water runoff from the adjacent field. This established flow of water has become a prescriptive right under the Prescription Act 1832, meaning that the continued flow of water cannot be legally obstructed after such a long period of uninterrupted use.

Diverting this water source will have a devastating impact on the ponds, likely leading to their desiccation and the destruction of the established ecosystem.

Critically, the pond network is an integral part of the setting of

the unique local heritage asset: the only surviving early electricity generating station

in Europe. This building is a significant historical landmark, and its setting, including the ponds and surrounding landscape, contributes significantly to its historical and architectural significance. The rural setting and surrounding countryside are part of the charm of the technology that nestles in this estate, as a time capsule. This historical and environmental context may well be protected by other conservation law, and that is now under threat. The proposed

land drainage diversion would severely compromise this historical setting and diminish the heritage value of the site.

LIFE CYCLE & BREEDING

Like other newts, T. cristatus develops in the water as a larva and returns to the

water each year for breeding. Adults spend around seven months of the year on land. After larval development in the first year, juveniles pass another year or two before reaching maturity; in the north and at higher elevations, this can take longer. The larval and juvenile stages are the riskiest for the newts, while survival is higher in adults. Once the risky stages passed, adult newts usually have a lifespan of seven to nine years, although individuals have reached 17 years in the wild.

Adult newts begin moving to their breeding sites in spring when temperatures stay above 4–5 °C (39–41 °F), usually in March. In the aquatic phase, crested newts are mostly nocturnal and, compared to smaller newt species, usually prefer the deeper parts of a water body, where they hide under vegetation. As with other newts, they have to occasionally move to the surface to breathe air. The aquatic phase serves not only for reproduction, but also offers more abundant prey, and immature crested newts frequently return to the water in spring even if they do not breed.

During the terrestrial phase, the newts use hiding places such as logs, bark, planks, stone walls, or small mammal burrows; several individuals may occupy such refuges at the same time. Since the newts generally stay very close to their aquatic breeding sites, the quality of the surrounding terrestrial habitat largely determines whether an otherwise suitable water body will be colonised. Great crested newts may also climb vegetation during their terrestrial phase, although the exact function of this behaviour is not known at present.

The juvenile efts often disperse to new breeding sites, while the adults in general move back to the same breeding sites each year. The newts do not migrate very far: they may cover around 100 metres (110 yd) in one night and rarely disperse much farther than one kilometre (0.62 mi). Over most of their range, they hibernate in winter, using mainly subterranean hiding places, where many individuals will often congregate.

PREDATORS & DIET

Northern crested newts feed mainly on invertebrates. During the land phase, prey include earthworms and other annelids, different insects and their larvae, woodlice, and snails and slugs. During the breeding season, they prey on various aquatic invertebrates (such as molluscs [particularly small bivalves], microcrustaceans, and insects), and also tadpoles and juveniles of other amphibians such as the common frog or common toad, and smaller newts (including conspecifics). Larvae, depending on their size, eat small invertebrates and tadpoles, and also smaller larvae of their own species.

The larvae are themselves eaten by various animals such as carnivorous invertebrates and water birds, and are especially vulnerable to predatory

fish. Adults generally avoid predators through their hidden lifestyle but are sometimes eaten by herons and other

birds, snakes such as the grass snake, and mammals such as shrews, badgers and

hedgehogs. They secrete the poison tetrodotoxin from their skin, albeit much less than for example the North American

Pacific newts (Taricha). The bright yellow or orange underside of crested newts is a warning coloration which can be presented in case of perceived danger. In such a posture, the newts typically roll up and secrete a milky substance.

CONSERVATION & THREATS

The northern crested newt is listed as species of Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, but populations are declining. It is rare in some parts of its range and listed in several national red lists.

The major reason for decline is habitat destruction through urban and

agricultural development, affecting the aquatic breeding sites as well as the land habitats. Their limited dispersal makes the newts especially vulnerable to fragmentation, i.e. the loss of connections for exchange between suitable habitats. Other threats include the introduction of fish and crayfish into breeding ponds, collection for the pet trade in its eastern range, warmer and wetter winters due to global warming, genetic pollution through hybridisation with other, introduced crested newt species, the use of road salt, and potentially the pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans.

The northern crested newt is listed in Berne Convention Appendix II as "strictly protected". It is also included in Annex II (species requiring designation of special areas of conservation) and IV (species in need of strict protection) of the EU habitats and species directive, as a European Protected Species. As required by these frameworks, its capture, disturbance, killing or trade, as well as the destruction of its habitats, are prohibited in most European countries. The EU habitats directive is also the basis for the Natura 2000 protected areas, several of which have been designated specifically to protect the northern crested newt.

Preservation of natural water bodies, reduction of fertiliser and pesticide use, control or eradication of introduced predatory fish, and the connection of habitats through sufficiently wide corridors of uncultivated land are seen as effective conservation actions. A network of aquatic habitats in proximity is important to sustain populations, and the creation of new breeding ponds is in general very effective as they are rapidly colonised when other habitats are nearby. In some cases, entire populations have been moved when threatened by development projects, but such translocations need to be carefully planned to be successful.

Strict protection of the northern crested newt in the United Kingdom has created conflicts with local development projects, but the species is also seen as a flagship species, whose conservation also benefits a range of other amphibians. Government agencies have issued specific guidelines for the mitigation of development impacts.

UK GOVERNMENT GUIDANCE - GREAT CRESTED NEWTS NEED PROTECTION AND LICENCES

What you must do to avoid harming great crested newts and when you’ll need a licence.

Great crested newts are a European protected species. The animals and their eggs, breeding sites and resting places are protected by law.

You may be able to get a licence from Natural England if you’re planning an activity and can’t avoid disturbing them or damaging their habitats (ponds and the land around ponds).

Use the Froglife website to identify great crested newts.

WHAT YOU MUST NOT DO

Things that would cause you to break the law include:

- capturing, killing, disturbing or injuring great crested newts deliberately

- damaging or destroying a breeding or resting place

- obstructing access to their resting or sheltering places (deliberately or by not taking enough care)

- possessing, selling, controlling or transporting live or dead newts, or parts of them

- taking great crested newt eggs

You could get an unlimited fine and up to 6 months in prison for each offence if you’re found guilty.

Find out what to do if you’ve seen wildlife crime and how to report

it.

ACTIVITIES THAT CAN HARM GREAT CRESTED NEWTS

Activities that can affect great crested newts include:

- maintaining or restoring ponds, woodland, scrub or rough grassland

- restoring forest areas to lowland heaths

- ploughing close to breeding ponds or other bodies of water

- removing dense vegetation and disturbing the ground

- removing materials like dead wood piled on the ground

- excavating the ground, for example to renovate a building

- filling in or destroying ponds or other water bodies

Building and development work can harm great crested newts and their habitats, for example if it:

- removes habitat or makes it unsuitable

- disconnects or isolates habitats, such as by splitting it up

- changes habitats of other species, reducing the newts’ food sources

- increases shade and silt in ponds or other water bodies used by the newts

- changes the water table

- introduces fish, which will eat newt eggs or young

- increases the numbers of people, traffic and pollutants in the area or the amount of chemicals that run off into ponds

In many cases you should be able to avoid harming the newts, damaging or blocking access to their habitats by adjusting your plans. Contact an ecologist for more information about how to avoid harming the newts.

If you can’t avoid this, you can apply for a mitigation licence from Natural England. You’ll need expert help from an ecologist:

- Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environment Management

- Environmental Data services (ENDS) Directory

Find out more about construction that affects protected species.

Other licences are available for different activities.

POND MANAGEMENT

You won’t need a licence for many cases of standard pond management works, but you will need to plan the work well to minimise the risk of deliberate killing, injuring or disturbing newts. By working carefully, you’ll make sure that your pond habitat recovers the following year.

Your work should normally be carried out in late autumn through winter, typically between early November to late January, when great crested newts are least likely to be present in ponds.

This time period varies per pond because some adults may live in some ponds in winter, or in some cases newts may leave the pond much earlier. If you have to do work in the summer months, for example because of ground conditions, then you’ll almost certainly need a licence.

You’ll need to consider the impact of the work on great crested newts before you start pond management. You should survey:

- the pond to check for great crested newts (or other protected species)

-

the area immediately around the pond to consider whether the work will affect surrounding terrestrial great crested newt habitat

You should remember that large machinery can damage habitat and hibernacula. You must not deposit the silt removed from ponds on areas used by great crested newts.

You should immediately stop work if you find great crested newts in the pond before or after you start work if you’re doing pond management work without a licence. You should start your work at a different time or do it in a different way to avoid harming the newts. If you can’t avoid harming the newts then you’ll need to get a conservation licence.

Check the Great Crested Newt Conservation Handbook for information on habitat management, pond creation and restoration.

ACTIVITIES YOU DON'T NEED A LICENCE FOR

Activities you can do that wouldn’t break that law include:

- rescuing a great crested newt if it would die otherwise

-

doing work to a pond during the winter when no great crested newts are likely to be present

MITIGATION

AND COMPENSATION PLANS

Your planning authority is likely to refuse planning permission if your proposal would harm protected species. You’ll need to show that you’ve considered the following steps.

Avoid harming the species, for example by locating the works far enough away from protected species.

If you cannot avoid affecting the species, reduce (mitigate) harm to them, for example by restoring habitats to how they were before the development. If avoidance and mitigation are not possible, compensate for any harmful effects, for example by creating new habitats.

You may need to include a mitigation strategy with your survey report if you’re applying for planning permission. The planning authority will review your mitigation plans along with the survey data to assess how your proposals will affect wildlife. If you’re applying for mitigation licences from Natural England, you’ll include mitigation plans and survey findings as part of your method statement.

Your mitigation strategy should aim to:

- maintain species’ population size and distribution

- enhance the population in the medium to long term

- avoid harming other species

GREAT CRESTED NEWT EVOLUTION

The northern crested newt sometimes hybridises with other crested newt species where their ranges meet, but overall, the different species are reproductively isolated. In a case study in the Netherlands, genes of the introduced Italian crested newt (T. carnifex) were found to introgress into the gene pool of the native northern crested newt. The closest relative of the northern crested newt, according to molecular phylogenetic analyses, is the Danube crested newt (T. dobrogicus).

In western France, the northern crested newt's range overlaps with that of the marbled newt (T. marmoratus), but the two species in general prefer different habitats. When they do occur in the same breeding ponds, they can form hybrids, which have intermediate characteristics. Hybrids resulting from the cross of a crested newt male with a marbled newt female are much rarer due to increased mortality of the larvae and consist only of males. In the reverse cross, males have lower survival rates than females. Overall, viability is reduced in these hybrids and they rarely backcross with their parent species. Hybrids made up 3–7% of the adult populations in different studies.

Little genetic variation was found over most of the species' range, except in the Carpathians. This suggests that the Carpathians was a refugium during the Last Glacial Maximum. The northern crested newt then expanded its range north-, east- and westwards when the climate rewarmed.

COURTSHIP DISPLAYS

Northern crested newts, like their relatives in the genus Triturus, perform a complex courtship display, where the male attracts a female through specific body movements and waves pheromones to her. The males are territorial and use small patches of clear ground as leks, or courtship arenas. When successful, they guide the female over a spermatophore they deposit on the ground, which she then takes up with her cloaca.

The eggs are fertilised internally, and the female deposits them individually, usually folding them into leaves of aquatic plants. A female takes around five minutes for the deposition of one egg. They usually lay around 200 eggs per season. Embryos are usually light-coloured, 1.8–2 mm in diameter with a 6 mm jelly capsule, which distinguishes them from eggs of other co-existing newt species that are smaller and darker-coloured. A genetic particularity shared with other Triturus species causes 50% of the embryos to die.

Larvae hatch after two to five weeks, depending on temperature. As in all salamanders and newts, forelimbs develop first, followed later by the back legs. Unlike smaller newts, crested newt larvae are mostly nektonic, swimming freely in the water column. Just before the transition to land, the larvae resorb their external gills; they can at this stage reach a size of 7 centimetres (2.8 in). Metamorphosis into terrestrial efts takes place two to four months after hatching, again depending on temperature. Survival of larvae from hatching to metamorphosis has been estimated at a mean of roughly 4%. In unfavourable conditions, larvae may delay their development and overwinter in water, although this seems to be less common than in the small-bodied newts.

TAXONOMY

The northern crested newt was described as Triton cristatus by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768. As Linnaeus had already used the name Triton for a genus of sea snails ten years before, Constantine Samuel Rafinesque introduced the new genus name Triturus in 1815, with T. cristatus as type species.

Over 40 scientific names introduced over time are now considered as synonyms, including Lacertus aquatilis, a nomen oblitum published four years before Laurenti's species name. Hybrids resulting from the cross of a crested newt male with a marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus) female were mistakenly described as distinct species Triton blasii, and the reverse hybrids as Triton trouessarti.

T. cristatus was long considered as a single species, the "crested newt", with several subspecies. Substantial genetic differences between these subspecies were, however, noted and eventually led to their recognition as full species, often collectively referred to as "T. cristatus species complex". There are now seven accepted species of crested newts, of which the northern crested newt is the most widespread.

AMPHIBIAN

CONSERVATION

Dramatic declines in amphibian populations, including population crashes and mass localized extinction, have been noted since the late 1980s from locations all over the world, and amphibian declines are thus perceived to be one of the most critical threats to global biodiversity. In 2004, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) reported stating that currently birds, mammals, and amphibians extinction rates were at minimum 48 times greater than natural extinction rates

- possibly 1,024 times higher. In 2006, there were believed to be 4,035 species of amphibians that depended on water at some stage during their life cycle. Of these, 1,356 (33.6%) were considered to be threatened and this figure is likely to be an underestimate because it excludes 1,427 species for which there was insufficient data to assess their status. A number of causes are believed to be involved, including habitat destruction and modification, over-exploitation, pollution, introduced species, global warming, endocrine-disrupting pollutants, destruction of the ozone layer (ultraviolet radiation has shown to be especially damaging to the skin, eyes, and eggs of amphibians), and diseases like chytridiomycosis. However, many of the causes of amphibian declines are still poorly understood, and are a topic of ongoing discussion.

POLLUTION AND PESTICIDES

The decline in amphibian and reptile populations has led to an awareness of the effects of pesticides on reptiles and amphibians. In the past, the argument that amphibians or reptiles were more susceptible to any chemical contamination than any land aquatic vertebrate was not supported by research until recently. Amphibians and reptiles have complex life cycles, live in different climate and ecological zones, and are more vulnerable to chemical exposure. Certain pesticides, such as organophosphates, neonicotinoids, and carbamates, react via cholinesterase inhibition. Cholinesterase is an enzyme that causes the hydrolysis of acetylcholine, an excitatory neurotransmitter that is abundant in the nervous system. AChE inhibitors are either reversible or irreversible, and carbamates are safer than organophosphorus insecticides, which are more likely to cause cholinergic poisoning. Reptile exposure to an AChE inhibitory pesticide may result in disruption of neural function in reptiles. The buildup of these inhibitory effects on motor performance, such as food consumption and other activities.

PROTECTION STRATEGIES

The Amphibian Specialist Group of the IUCN is spearheading efforts to implement a comprehensive global strategy for amphibian conservation. Amphibian Ark is an organization that was formed to implement the ex-situ conservation recommendations of this plan, and they have been working with zoos and aquaria around the world, encouraging them to create assurance colonies of threatened amphibians. One such project is the

Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project that built on existing conservation efforts in Panama to create a country-wide response to the threat of chytridiomycosis.

Another measure would be to stop exploitation of frogs for human consumption. In the

Middle

East, a growing appetite for eating frog legs and the consequent gathering of them for food was already linked to an increase in

mosquitoes and thus has direct consequences for human health.

Please

use the Index below to navigate the Animal Kingdom:-

|

AMPHIBIANS |

Such

as frogs (class: Amphibia), Newts,

Toads |

|

ANNELIDS |

As

in Earthworms (phyla: Annelida) |

|

ANTHROPOLOGY |

Neanderthals,

Homo Erectus (Extinct) |

|

ARACHNIDS |

Spiders

(class: Arachnida) |

|

BIRDS

|

Such

as Eagles, Albatross

(class: Aves) |

|

CETACEANS

|

such

as Whales

& Dolphins

( order:Cetacea) |

|

CRUSTACEANS |

such

as crabs (subphyla: Crustacea) |

|

DINOSAURS

|

Tyranosaurus

Rex,

Brontosaurus (Extinct) |

|

ECHINODERMS |

As

in Starfish (phyla: Echinodermata) |

|

FISH

|

Sharks,

Tuna (group: Pisces) |

|

HUMANS

-

MAN |

Homo

Sapiens THE

BRAIN |

|

INSECTS |

Ants,

(subphyla: Uniramia class:

Insecta) |

|

LIFE

ON EARTH

|

Which

includes PLANTS

non- animal life |

|

MAMMALS

|

Warm

blooded animals (class: Mammalia) |

|

MARSUPIALS |

Such

as Kangaroos

(order: Marsupialia) |

|

MOLLUSKS |

Such

as octopus (phyla: Mollusca) |

|

PLANTS |

Trees

- |

|

PRIMATES |

Gorillas,

Chimpanzees

(order: Primates) |

|

REPTILES |

As

in Crocodiles,

Snakes (class: Reptilia) |

|

RODENTS |

such

as Rats, Mice (order: Rodentia) |

|

SIMPLE

LIFE FORMS

|

As

in Amoeba, plankton (phyla: protozoa) |

|

|

It's

sad to think that one day, the planet Earth may be gone.

This is despite our best efforts to save her. The good news is

that provided we all work together, we can preserve the status

quo on our beautiful blue world, for centuries to come.

Provided that is we heed the warnings nature is sending us, such

as global warming and other pollutions.

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/great-crested-newts-protection-surveys-and-licences

https://www.froglife.org/amphibians-and-reptiles/great-crested-newt/

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wildlife-crime-and-how-to-report-it

http://www.cieem.net/members-directory

https://www.endsdirectory.com/

https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/great-crested-newt-licences

https://www.gov.uk/construction-near-protected-areas-and-wildlife

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/survey-or-research-licence-for-protected-species

http://www.froglife.org/info-advice/great-crested-newt-conservation-handbook/

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/construction-near-protected-areas-and-wildlife

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/construction-near-protected-areas-and-wildlife

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/great-crested-newts-protection-surveys-and-licences

|