|

JULY

2012 - EXXON VALDEZ DISMANTLED FOR SCRAP

The Indian Supreme Court ruled that the ore carrier Oriental Nicety could be beached and dismantled for scrap in the Indian port of Alang, the world's largest scrap metal yard.

Nothing inherently unusual in that, perhaps. But the story is notable given that before it was the Oriental Nicety, the vessel in question was known as the Dong Fang Ocean, and before that had been dubbed, in reverse order, the Mediterranean, the S/R Mediterranean and the Sea River Mediterranean. The second name it had carried in its life was the Exxon Mediterranean; and before that, for four years from its launch in 1986, it was an oil tanker known as the Exxon Valdez.

MARCH

24 1989

The Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred in Prince William Sound, Alaska, on March 24, 1989, when Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker bound for Long Beach, California struck Prince William Sound's Bligh Reef and spilled 260,000 to 750,000 barrels (41,000 to 119,000 m3) of crude oil. It is considered to be one of the most devastating human-caused environmental disasters. The Valdez spill was the largest ever in U.S. waters until the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, in terms of volume released. However, Prince William Sound's remote location, accessible only by helicopter, plane, and boat, made government and industry response efforts difficult and severely taxed existing plans for response. The region is a habitat for salmon, sea otters, seals and seabirds. The oil, originally extracted at the Prudhoe Bay oil field, eventually covered 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of coastline, and 11,000 square miles (28,000 km2) of ocean. Then Exxon CEO, Lawrence G. Rawl, shaped the company's response.

According to official reports, the ship was carrying approximately 55 million US gallons (210,000 m3) of oil, of which about 11 to 32 million US gallons (42,000 to 120,000 m3) were spilled into the Prince William

Sound. A figure of 11 million US gallons (42,000 m3) was a commonly accepted estimate of the spill's volume and has been used by the State of Alaska's Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and environmental groups such as Greenpeace and the Sierra Club. Some groups, such as Defenders of Wildlife, dispute the official estimates, maintaining that the volume of the spill, which was calculated by subtracting the volume of material removed from the vessel's tanks after the spill from the volume of the original cargo, has been underreported. Alternative calculations, based on the assumption that the official reports underestimated how much seawater had been forced into the damaged tanks, placed the total at 25 to 32 million US gallons (95,000 to 120,000 m3).

Identified causes

Multiple factors have been identified as contributing to the incident:

Exxon Shipping Company failed to supervise the master and provide a rested and sufficient crew for Exxon Valdez. The NTSB found this was widespread throughout the industry, prompting a safety recommendation to Exxon and to the industry.

The third mate failed to properly maneuver the vessel, possibly due to fatigue or excessive workload.

Exxon Shipping Company failed to properly maintain the Raytheon Collision Avoidance System (RAYCAS)

radar, which, if functional, would have indicated to the third mate an impending collision with the Bligh Reef by detecting the "radar reflector", placed on the next rock inland from Bligh Reef for the purpose of keeping boats on course via radar.

The captain was confirmed to be asleep when the ship crashed in Prince William Sound's reef. In light of the other findings, investigative reporter Greg Palast stated in 2008 "Forget the drunken skipper fable. As to Captain Joe Hazelwood, he was below decks, sleeping off his bender. At the helm, the third mate never would have collided with Bligh Reef had he looked at his RAYCAS radar. But the radar was not turned on. In fact, the tanker's radar was left broken and disabled for more than a year before the disaster, and Exxon management knew it. It was [in Exxon's view] just too expensive to fix and operate." Exxon blamed Captain Hazelwood for the grounding of the tanker.

Other factors, according to an MIT course entitled "Software System Safety" by Professor Nancy G. Leveson, included:

Tanker crews were not told that the previous practice of the Coast Guard tracking ships out to Bligh reef had ceased.

The oil industry promised, but never installed, state-of-the-art iceberg monitoring equipment.

Exxon Valdez was sailing outside the normal sea lane to avoid small icebergs thought to be in the area.

The 1989 tanker crew was half the size of the 1977 crew, worked 12–14 hour shifts, plus overtime. The crew was rushing to leave Valdez with a load of oil.

Coast Guard tanker inspections in Valdez were not done, and the number of staff was reduced.

Lack of available equipment and personnel hampered the spill cleanup

This disaster resulted in International Maritime Organization introducing comprehensive Marine pollution prevention rules (MARPOL AND IOPP) through various conventions. The rules were ratified by member countries and, after International Ship Management rules, the Ships are being operated with a common objective of "safer ships and cleaner oceans".

Clean-up measures and environmental impact

There was use of a dispersant, a surfactant and solvent mixture. A private company applied dispersant on March 24 with a helicopter and dispersant bucket. Because there was not enough wave action to mix the dispersant with the oil in the water, the use of the dispersant was discontinued. One trial explosion was also conducted during the early stages of the spill to burn the oil, in a region of the spill isolated from the rest by another explosion. The test was relatively successful, reducing 113,400 liters of oil to 1,134 liters of removable residue, but because of unfavorable weather no additional burning was attempted. The dispersant Corexit 9580 was tried as part of the cleanup. Corexit has been found to be toxic to cleanup workers and wildlife while breaking down oil.

Mechanical cleanup was started shortly afterwards using booms and skimmers, but the skimmers were not readily available during the first 24 hours following the spill, and thick oil and kelp tended to clog the equipment.

Exxon was widely criticized for its slow response to cleaning up the disaster and John Devens, the mayor of Valdez, has said his community felt betrayed by Exxon's inadequate response to the crisis. More than 11,000 Alaska residents, along with some Exxon employees, worked throughout the region to try to restore the environment.

Because Prince William Sound contained many rocky coves where the oil collected, the decision was made to displace it with high-pressure hot water. However, this also displaced and destroyed the microbial populations on the shoreline; many of these organisms (e.g. plankton) are the basis of the coastal marine food chain, and others (e.g. certain bacteria and fungi) are capable of facilitating the biodegradation of oil. At the time, both scientific advice and public pressure was to clean everything, but since then, a much greater understanding of natural and facilitated remediation processes has developed, due somewhat in part to the opportunity presented for study by the Exxon Valdez spill. Despite the extensive cleanup attempts, less than ten percent of the oil was recovered and a study conducted by NOAA determined that as of early 2007 more than 26 thousand U.S. gallons (98 m3) of oil remain in the sandy soil of the contaminated shoreline, declining at a rate of less than 4% per year.

In 1992, Exxon released a video titled Scientists and the Alaska Oil Spill. It was provided to schools with the label "A Video for Students".

Both the long-term and short-term effects of the oil spill have been studied. Immediate effects included the deaths of, at the best estimates, 100,000 to as many as 250,000 seabirds, at least 2,800 sea otters, approximately 12 river otters, 300 harbor seals, 247 Bald Eagles, and 22 orcas, as well as the destruction of billions of salmon and herring eggs. The effects of the spill continued to be felt for many years afterwards. Overall reductions in population were seen in various ocean animals, including stunted growth in pink salmon populations. The effect on salmon and other prey populations in turn adversely affected killer whales in Prince William Sound and Alaska's Kenai Fjords region. Eleven members (about half) of one resident pod disappeared in the following year. By 2009, scientists estimated the AT1 transient population (considered part of a larger population of 346 transients), numbered only 7 individuals and had not reproduced since the spill, this population is expected to die out. Sea otters and ducks also showed

higher death rates in following years, partially because they ingested prey from contaminated soil and from ingestion of oil residues on hair due to grooming.

Some twenty years after the spill, a team from the University of North Carolina found that the effects were lasting far longer than expected. The team estimates some shoreline Arctic habitats may take up to thirty years to recover. The spill occurred on March 24, 1989. Exxon Mobil denies any concerns over this, stating that they anticipated a remaining fraction that they assert will not cause any long-term ecological impacts, according to the conclusions of 350 peer-reviewed studies. However, a NOAA study concluded that this

contamination can produce chronic low-level exposure, discourage subsistence where the contamination is heavy, and decrease the "wilderness character" of the area.

Litigation and cleanup costs

In the case of Baker v. Exxon, an Anchorage jury awarded $287 million for actual damages and $5 billion for punitive damages. The punitive damages amount was equal to a single year's profit by Exxon at that time. To protect itself in case the judgment was affirmed, Exxon obtained a $4.8 billion credit line from J.P. Morgan & Co. J.P. Morgan created the first modern credit default swap in 1994, so that Morgan's would not have to hold as much money in reserve (8% of the loan under Basel I) against the risk of Exxon's default.

Meanwhile, Exxon appealed the ruling, and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the original judge, Russel Holland, to reduce the punitive damages. On December 6, 2002, the judge announced that he had reduced the damages to $4 billion, which he concluded was justified by the facts of the case and was not grossly excessive. Exxon appealed again and the case returned to court to be considered in light of a recent Supreme Court ruling in a similar case, which caused Judge Holland to increase the punitive damages to $4.5 billion, plus interest.

After more appeals, and oral arguments heard by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals on January 27, 2006, the damages award was cut to $2.5 billion on December 22, 2006. The court cited recent Supreme Court rulings relative to limits on punitive damages.

Exxon appealed again. On May 23, 2007, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals denied ExxonMobil's request for a third hearing and let stand its ruling that Exxon owes $2.5 billion in punitive damages. Exxon then appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case. On February 27, 2008, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for 90 minutes. Justice Samuel Alito, who at the time, owned between $100,000 and $250,000 in Exxon stock, recused himself from the case. In a decision issued June 25, 2008, Justice David Souter issued the judgment of the court, vacating the $2.5 billion award and remanding the case back to a lower court, finding that the damages were excessive with respect to maritime common law. Exxon's actions were deemed "worse than negligent but less than malicious." The judgment limits punitive damages to the compensatory damages, which for this case were calculated as $507.5 million. The basis for limiting punitive damages to no more than twice[clarification needed] the actual damages has no precedent to support

it. Some lawmakers, such as Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick J. Leahy, have decried the ruling as "another in a line of cases where this Supreme Court has misconstrued congressional intent to benefit large corporations."

Exxon's official position is that punitive damages greater than $25 million are not justified because the spill resulted from an accident, and because Exxon spent an estimated $2 billion cleaning up the spill and a further $1 billion to settle related civil and criminal charges. Attorneys for the plaintiffs contended that Exxon bore responsibility for the accident because the company "put a drunk in charge of a tanker in Prince William Sound."

Exxon recovered a significant portion of clean-up and legal expenses through insurance claims associated with the grounding of the Exxon Valdez. Also, in 1991, Exxon made a quiet, separate financial settlement of damages with a group of seafood producers known as the Seattle Seven for the disaster's effect on the Alaskan seafood industry. The agreement granted $63.75 million to the Seattle Seven, but stipulated that the seafood companies would have to repay almost all of any punitive damages awarded in other civil proceedings. The $5 billion in punitive damages was awarded later, and the Seattle Seven's share could have been as high as $750 million if the damages award had held. Other plaintiffs have objected to this secret arrangement, and when it came to light, Judge Holland ruled that Exxon should have told the jury at the start that an agreement had already been made, so the jury would know exactly how much Exxon would have to pay.

POLITICAL REFORMS

Coast Guard report

A report by the US National Response Team summarized the event and made a number of recommendations, such as changes to the work patterns of Exxon crew in order to address the causes of the accident.

Oil Pollution Act of 1990

In response to the spill, the United States Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA). The legislation included a clause that prohibits any vessel that, after March 22, 1989, has caused an oil spill of more than 1 million US gallons (3,800 m3) in any marine area, from operating in Prince William

Sound.

In April 1998, the company argued in a legal action against the Federal government that the ship should be allowed back into Alaskan waters. Exxon claimed OPA was effectively a bill of attainder, a regulation that was unfairly directed at Exxon

alone. In 2002, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against Exxon. As of 2002, OPA had prevented 18 ships from entering Prince William Sound.

OPA also set a schedule for the gradual phase in of a double hull design, providing an additional layer between the oil tanks and the ocean. While a double hull would likely not have prevented the Valdez disaster, a Coast Guard study estimated that it would have cut the amount of oil spilled by 60 percent.

The Exxon Valdez supertanker was towed to San Diego, arriving on July 10. Repairs began on July 30.

Approximately 1,600 short tons (1,500 t) of steel were removed and replaced. In June 1990 the tanker, renamed S/R Mediterranean, left harbor after $30 million of

repairs. It was still sailing as of January 2010, registered in Panama. The vessel was then owned by a Hong Kong company, who operated it under the name Oriental Nicety. In August 2012, the Exxon Valdez was beached at Alang, India and dismantled.

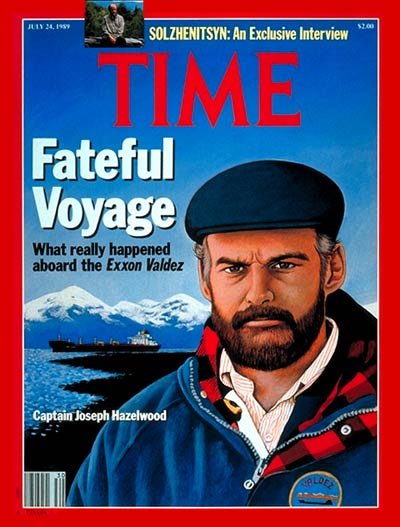

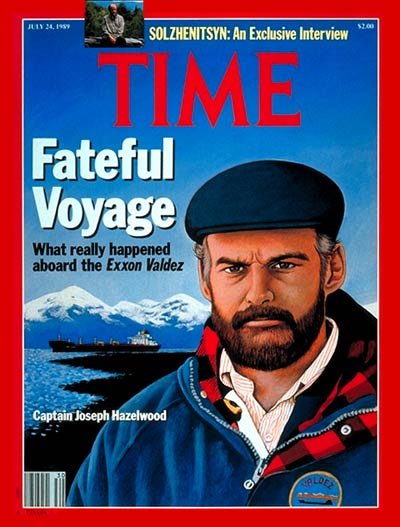

In 2009, Exxon Valdez Captain Joseph Hazelwood offered a "heartfelt apology" to the people of Alaska, suggesting he had been wrongly blamed for the disaster: "The true story is out there for anybody who wants to look at the facts, but that's not the sexy story and that's not the easy story," he said. Yet Hazelwood said he felt Alaskans always gave him a fair shake.

Alaska regulations

In the aftermath of the spill, Alaska governor Steve Cowper issued an executive order requiring two tugboats to escort every loaded tanker from Valdez out through Prince William Sound to Hinchinbrook Entrance. As the plan evolved in the 1990s, one of the two routine tugboats was replaced with a 210-foot (64 m) Escort Response Vehicle (ERV). The majority of tankers at Valdez are no longer single-hulled, Congress has enacted legislation requiring all tankers to be double-hulled by 2015.

Opposition to oil drilling

The Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union, representing approximately 40,000 US workers, announced opposition to drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) until Congress enacted a comprehensive national energy policy.

Economic and personal impact

In 1991, following the collapse of the local marine population (particularly clams, herring, and seals) the Chugach Alaska Corporation, an Alaska Native Corporation, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. It has since recovered.

According to several studies funded by the state of Alaska, the spill had both short-term and long-term economic effects. These included the loss of recreational sports, fisheries, reduced tourism, and an estimate of what economists call "existence value", which is the value to the public of a pristine Prince William Sound.

The economy of the city of Cordova, Alaska was adversely affected after the spill damaged stocks of salmon and herring in the area. Several residents, including one former mayor, committed suicide after the spill.

EXXON

VALDEZ DETAILS of the ACCIDENT

No one anticipated any unusual problems as the Exxon Valdez left the Alyeska Pipeline Terminal at 9:12 p.m., Alaska Standard Time, on March 23,1989. The 987foot ship, second newest in Exxon Shipping Company's 20-tanker fleet, was loaded with 53,094,5 10 gallons (1,264,155 barrels) of North Slope crude oil bound for Long Beach, California. Tankers carrying North Slope crude oil had safely transited Prince William Sound more than 8,700 times in the 12 years since oil began flowing through the trans-Alaska pipeline, with no major disasters and few serious incidents. This experience gave little reason to suspect impending disaster. Yet less than three hours later, the Exxon Valdez grounded at Bligh Reef, rupturing eight of its 11 cargo tanks and spewing some 10.8 million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound.

Shortly after leaving the Port of Valdez, the Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef. This picture was taken 3 days after the vessel grounded, just before a storm arrived.

Until the Exxon Valdez piled onto Bligh Reef, the system designed to carry 2 million barrels of North Slope oil to West Coast and Gulf Coast markets daily had worked perhaps too well. At least partly because of the success of the Valdez tanker trade, a general complacency had come to permeate the operation and oversight of the entire system. That complacency and success were shattered when the Exxon Valdez ran hard aground shortly after midnight on March 24.

No human lives were lost as a direct result of the disaster, though four deaths were associated with the cleanup effort. Indirectly, however, the human and natural losses were immense-to fisheries, subsistence livelihoods, tourism, wildlife. The most important loss for many who will never visit Prince William Sound was the aesthetic sense that something sacred in the relatively unspoiled land and waters of Alaska had been defiled.

Industry's insistence on regulating the Valdez tanker trade its own way, and government's incremental accession to industry pressure, had produced a disastrous failure of the system. The people of Alaska's Southcentral coast-not to mention Exxon and the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company-would come to pay a heavy price. The American people, increasingly anxious over environmental degradation and devoted to their image of Alaska's wilderness, reacted with anger. A spill that ranked 34th on a list of the world's largest oil spills in the past 25 years came to be seen as the nation's biggest environmental disaster since Three Mile Island.

The Exxon Valdez had reached the Alyeska Marine Terminal at 11:30 p.m. on March 22 to take on cargo. It carried a crew of 19 plus the captain. Third Mate Gregory Cousins, who became a central figure in the grounding, was relieved of watch duty at 11:50 p.m. Ship and terminal crews began loading crude oil onto the tanker at 5:05 a.m. on March 23 and increased loading to its full rate of 100,000 barrels an hour by 5:30 a.m. Chief Mate James R. Kunkel supervised the loading.

March 23, 1989 was a rest day of sorts for some members of the Exxon Valdez crew. Capt. Joseph Hazelwood, chief engineer Jerry Glowacki and radio officer Joel Roberson left the Exxon Valdez about 11:00 a.m., driven from the Alyeska terminal into the town of Valdez by marine pilot William Murphy, who had piloted the Exxon Valdez into port the previous night and would take it back out through Valdez Narrows on its fateful trip to Bligh Reef. When the three ship's officers left the terminal that day, they expected the Exxon Valdez's sailing time to be 10 p.m. that evening. The posted sailing time was changed, however, during the day, and when the party arrived back at the ship at 8:24 p.m., they learned the sailing time had been fixed at 9 p.m.

Hazelwood spent most of the day conducting ship's business, shopping and, according to testimony before the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), drinking alcoholic beverages with the other ship's officers in at least two Valdez bars. Testimony indicated Hazelwood drank nonalcoholic beverages that day at lunch, a number of alcoholic drinks late that afternoon while relaxing in a Valdez bar, and at least one more drink at a bar while the party waited for pizza to take with them back to the ship.

Loading of the Exxon Valdez had been completed for an hour by the time the group returned to the ship. They left Valdez by taxi cab at about 7:30 p.m., got through Alyeska terminal gate security at 8:24 p.m. and boarded ship. Radio officer Roberson, who commenced prevoyage tests and checks in the radio room soon after arriving at the ship, later said no one in the group going ashore had expected the ship to be ready to leave as soon as they returned.

Both the cab driver and the gate security guard later testified that no one in the party appeared to be intoxicated. A ship's agent who met with Hazelwood after he got back

on the ship said it appeared the captain may have been drinking because his eyes were

watery, but she did not smell alcohol on his breath. Ship's pilot Murphy, however,

later indicated that he did detect the odor of alcohol on Hazelwood's breath.

Hazelwood's activities in town that day and on the ship that night would become a key focus of accident inquiries, the cause of a state criminal prosecution, and the basis of widespread media sensation. Without intending to minimize the impact of Hazelwood's actions, however, one basic conclusion of this report is that the grounding at Bligh Reef represents much more than the error of a possibly drunken skipper: It was the result of the gradual degradation of oversight and safety practices that had been intended, 12 years before, to safeguard and backstop the inevitable mistakes of human beings.

Third Mate Cousins performed required tests of navigational, mechanical and safety gear at 7:48 p.m., and all systems were found to be in working order. The Exxon Valdez slipped its last mooring line at 9:12 p.m. and, with the assistance of two tugboats, began maneuvering away from the berth. The tanker's deck log shows it was clear of the dock at 9:21 p.m.

Dock to grounding

The ship was under the direction of pilot Murphy and accompanied by a single tug for the passage through Valdez Narrows, the constricted harbor entrance about 7 miles from the berth. According to Murphy, Hazelwood left the bridge at 9:35 p.m. and did not return until about 11:10 p.m., even though Exxon company policy requires two ship's officers on the bridge during transit of Valdez Narrows.

The passage through Valdez Narrows proceeded uneventfully. At 10:49 p.m. the ship reported to the Valdez Vessel Traffic Center that it had passed out of the narrows and was increasing speed. At 11:05 p.m. Murphy asked that Hazelwood be called to the bridge in anticipation of his disembarking from the ship, and at 11: 10 p.m. Hazelwood returned. Murphy disembarked at 11:24 p.m., with assistance from Third Mate Cousins. While Cousins was helping Murphy and then helping stow the pilot ladder, Hazelwood was the only officer on the bridge and there was no lookout even though one was required, according to an NTSB report.

At 11:25 p.m. Hazelwood informed the Vessel Traffic Center that the pilot had departed and that he was increasing speed to sea speed. He also reported that "judging, ah, by our radar, we'll probably divert from the TSS [traffic separation scheme] and end up in the inbound lane if there is no conflicting traffic." The traffic center indicated concurrence, stating there was no reported traffic in the inbound lane.

The traffic separation scheme is designed to do just that-separate incoming and outgoing tankers in Prince William Sound and keep them in clear, deep waters during their transit. It consists of inbound and outbound lanes, with a half-mile-wide separation zone between them. Small icebergs from nearby Columbia Glacier occasionally enter the traffic lanes. Captains had the choice of slowing down to push through them safely or deviating from their lanes if traffic permitted. Hazelwood's report, and the Valdez traffic center's concurrence, meant the ship would change course to leave the western, outbound lane, cross the separation zone and, if necessary, enter the eastern, inbound lane to avoid floating ice. At no time did the Exxon Valdez report or seek permission to depart farther east from the inbound traffic lane; but that is exactly what it did.

At 11:30 p.m. Hazelwood informed the Valdez traffic center that he was turning the ship toward the east on a heading of 200 degrees and reducing speed to "wind my way through the ice" (engine logs, however, show the vessel's speed continued to increase). At 11: 39 Cousins plotted a fix that showed the ship in the middle of the traffic separation scheme. Hazelwood ordered a further course change to a heading of 180 degrees (due south) and, according to the helmsman, directed that the ship be placed on autopilot. The second course change was not reported to the Valdez traffic center. For a total of 19 or 20 minutes the ship sailed south-through the inbound traffic lane, then across its easterly boundary and on toward its peril at Bligh Reef. Traveling at approximately 12 knots, the Exxon Valdez crossed the traffic lanes' easterly boundary at 11:47 p.m.

At 11:52 p.m. the command was given to place the ship's engine on "load program up"-a computer program that, over a span of 43 minutes, would increase engine speed from 55 RPM to sea speed full ahead at 78.7 RPM. After conferring with Cousins about where and how to return the ship to its designated traffic lane, Hazelwood left the bridge. The time, according to NTSB testimony, was approximately 11:53 p.m.

By this time Third Mate Cousins had been on duty for six hours and was scheduled to be relieved by Second Mate Lloyd LeCain. But Cousins, knowing LeCain had worked long hours during loading operations during the day, had told the second mate he could take his time in relieving him. Cousins did not call LeCain to awaken him for the midnight-to-4-a.m. watch, instead remaining on duty himself

Cousins was the only officer on the bridge-a situation that violated company policy and perhaps contributed to the accident. A second officer on the bridge might have been more alert to the danger in the ship's position, the failure of its efforts to turn, the autopilot steering status, and the threat of ice in the tanker lane.

Cousins' duty hours and rest periods became an issue in subsequent investigations. Exxon Shipping Company has said the third mate slept between I a.m. and 7:20 a.m. the morning of March 23 and again between 1: 30 p.m. and 5 p.m., for a total of nearly 10 hours sleep in the 24 hours preceding the accident. But testimony before the NTSB suggests that Cousins "pounded the deck" that afternoon, that he did paperwork in his cabin, and that he ate dinner starting at 4:30 p.m. before relieving the chief mate at 5 p.m. An NTSB report shows that Cousins' customary in-port watches were scheduled from 5:50 a.m. to 11:50 a.m. and again from 5:50 p.m. to 11:50 p.m. Testimony before the NTSB suggests that Cousins may have been awake and generally at work for up to 18 hours preceding the accident.

Appendix F of this report documents a direct link between fatigue and human performance error generally and notes that 80 percent or more of marine accidents are attributable to human error. Appendix F also discusses the impact of environmental factors such as long work hours, poor work conditions (such as toxic fumes), monotony and sleep deprivation. "This can create a scenario where a pilot and/or crew members may become the 'accident waiting to happen.' ... It is conceivable," the report continues, "that excessive work hours (sleep deprivation) contributed to an overall impact of fatigue, which in turn contributed to the Exxon Valdez grounding."

Manning policies also may have affected crew fatigue. Whereas tankers in the 1950s carried a crew of 40 to 42 to manage about 6.3 million gallons of oil, according to Arthur McKenzie of the Tanker Advisory Center in New York, the Exxon Valdez carried a crew of 19 to transport 53 million gallons of oil.

Minimum vessel manning limits are set by the U.S. Coast Guard, but without any agencywide standard for policy. The Coast Guard has certified Exxon tankers for a minimum of 15 persons (14 if the radio officer is not required). Frank Iarossi, president of Exxon Shipping Company, has stated that his company's policy is to reduce its standard crew complement to 16 on fully automated, diesel-powered vessels by 1990. "While Exxon has defended their actions as an economic decision," the manning report says, "criticism has been leveled against them for manipulating overtime records to better justify reduced manning levels."

Iarossi and Exxon maintain that modem automated vessel technology permits reduced manning without compromise of safety or function. "Yet the literature on the subject suggests that automation does not replace humans in systems, rather, it places the human in a different, more demanding role. Automation typically reduces manual workload but increases mental workload." (Appendix F)

Whatever the NTSB or the courts may finally determine concerning Cousins' work hours that day, manning limits and crew fatigue have received considerable attention as contributing factors to the accident. The Alaska Oil Spill Commission recommends that crew levels be set high enough not only to permit safe operations during ordinary conditions-which, in the Gulf of Alaska, can be highly demanding-but also to provide enough crew backups and rest periods that crisis situations can be confronted by a fresh, well-supported crew.

Accounts and interpretations differ as to events on the bridge from the time Hazelwood left his post to the moment the Exxon Valdez struck Bligh Reef. NTSB testimony by crew members and interpretations of evidence by the State of Alaska conflict in key areas, leaving the precise timing of events still a mystery. But the rough outlines are discernible:

Some time during the critical period before the grounding during the first few minutes of Good Friday, March 24, Cousins plotted a fix indicating it was time to turn the vessel back toward the traffic lanes. About the same time, lookout Maureen Jones reported that Bligh Reef light appeared broad off the starboard bow-i.e., off the bow at an angle of about 45 degrees. The light should have been seen off the port side (the left side of a ship, facing forward); its position off the starboard side indicated great peril for a supertanker that was out of its lanes and accelerating through close waters. Cousins gave right rudder commands to cause the desired course change and took the ship off autopilot. He also phoned Hazelwood in his cabin to inform him the ship was turning back toward the traffic lanes and that, in the process, it would be getting into ice. When the vessel did not turn swiftly enough, Cousins ordered further right rudder with increasing urgency. Finally, realizing the ship was in serious trouble, Cousins phoned Hazelwood again to report the danger-and at the end of the conversation, felt an initial shock to the vessel. The grounding, described by helmsman Robert Kagan as "a bumpy ride" and by Cousins as six "very sharp jolts," occurred at 12:04 a.m.

ON THE ROCKS

The vessel came to rest facing roughly southwest, perched across its middle on a pinnacle of Bligh Reef Eight of 11 cargo tanks were punctured. Computations aboard the Exxon Valdez showed that 5.8 million gallons had gushed out of the tanker in the first three and a quarter hours. Weather conditions at the site were, reported to be 33 degrees F, slight drizzle rain/snow mixed, north winds at 10 knots and visibility 10 miles at the time of the grounding.

The Exxon Valdez nightmare had begun. Hazelwood-perhaps drunk, certainly facing a position of great difficulty and confusion-would struggle vainly to power the ship off its perch on Bligh Reef. The response capabilities of Alyeska Pipeline Service Company to deal with the spreading sea of oil would be tested and found to be both unexpectedly slow and woefully inadequate. The worldwide capabilities of Exxon Corp. would mobilize huge quantities of equipment and personnel to respond to the spill-but not in the crucial first few hours and days when containment and cleanup efforts are at a premium. The U.S. Coast Guard would demonstrate its prowess at ship salvage, protecting crews and lightering operations, but prove utterly incapable of oil spill containment and response. State and federal agencies would show differing levels of preparedness and command capability. And the waters of Prince William Sound-and eventually more than 1,000 miles of beach in Southcentral Alaska-would be fouled by 10.8 million gallons of crude oil.

Pooled oil from the Exxon Valdez sits between rocks on the shore. Most of the spilled oil decomposed. Cleanup crews recovered about 14 percent; 13 percent sank to the sea floor; about two percent remained on the beaches, but today, very little remains

After feeling the grounding Hazelwood rushed to the bridge, arriving as the ship came to rest. He immediately gave a series of rudder orders in an attempt to free the vessel, and power to the ship's engine remained in the "load program up" condition for about 15 minutes after impact. Chief Mate Kunkel went to the engine control room and determined that eight cargo tanks and two ballast tanks had been ruptured; he concluded the cargo tanks had lost an average of 10 feet of cargo, with approximately 67 feet of

cargo remaining in each. He informed Hazelwood of his initial damage assessment and was instructed to perform stability and stress analysis. At 12:19 a.m. Hazelwood ordered that the vessel's engine be reduced to idle speed.

At 12:26 a.m., Hazelwood radioed the Valdez traffic center and reported his predicament to Bruce Blandford, a civilian employee of the Coast Guard who was on duty. "We've fetched up, ah, hard aground, north of Goose Island, off Bligh Reef and, ah, evidently leaking some oil and we're gonna be here for a while and, ah, if you want, ah, so you're notified." That report triggered a nightlong cascade of phone calls reaching from Valdez to Anchorage to Houston and eventually around the world as the magnitude of the spill became known and Alyeska and Exxon searched for cleanup machinery and materials.

Hazelwood, meanwhile, was not finished with efforts to power the Exxon Valdez off the reef. At approximately 12:30 a.m., Chief Mate Kunkel used a computer program to determine that though stress on the vessel exceeded acceptable limits, the ship still had required stability. He went to the bridge to advise Hazelwood that the vessel should not go to sea or leave the area. The skipper directed him to return to the control room to continue assessing the damage and to determine available options. At 12:35 p.m., Hazelwood ordered the engine back on-and eventually to "full

ahead" - and began another series of rudder commands in an effort to free the vessel. After running his computer program again another way, Kunkel concluded that the ship did not have acceptable stability without being supported by the reef. The chief mate relayed his new analysis to the captain at I a.m. and again recommended that the ship not leave the area. Nonetheless, Hazelwood kept the engine running until 1:41 a.m., when he finally abandoned efforts to get the vessel off the reef.

HUMAN

ERROR

Captain John Hazelwood was a convenient scapegoat for his negligence, sheltering Exxon from public pressure during the spill. Although Hazelwood had a blood alcohol level in excess of legal standards, it was merely a contributing factor to a thwarted policy by the oil companies to work around traffic management and corporate pressures toward profiteering.

Hazelwood informed Valdez Traffic Control, he would be transiting wider than the normal shipping, essentially using the northbound land, for a southbound voyage. Ice chunks, known as "calves" or "growlers" were drifting into the southbound lane and Hazelwood announced his intention to "wend" his way through the

ice.

In doing so, he steered the ship more than 45 degrees into the southbound land, then ordering a course correction once they past the Bligh Island marker bouy. The relieving first officer misunderstood the ships position on radar. A crewman aboard the Valdez noticed the bouy on the wrong side of the vessel and dashed to inform the bridge. The would not be enough time to stop the ship (something which normally requires several miles). The Valdez hit the reef while operating at sea speed.

To add insult to injury, Hazelwood neglected to inform Exxon or Valdez Traffic for an extended period. Hazelwood made several attemptd to free the vessel from the rocks, which likely caused other cargo tanks to rupture, thus needlessly increasing the magnitude of the spill.

Hazelwood was also a harbour pilot, which eliminated an extra skillful pair of eyes on the bridge. The grounding was largely attributed to the first officer

LINKS

http://news.discovery.com/earth/exxon-valdez-1986-2012.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10324021

Dong

Fang Ocean Auke Visser's

Historical Tankers..

Dong

Fang Ocean - Type of ship: Cargo Ship - Callsign: 3EPL6 VesselTracker.

2010.

ABS

Record: Dong Fang Ocean American Bureau of Shipping. 2010.

Frequently

Asked Questions About the Spill Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee

Council.

Bluemink,

Elizabeth (Thursday, 10 June 2010). Size

of Exxon spill remains disputed Anchorage Daily News.

The

former Exxon Valdez faces retirement The Baltimore Sun.

9th

Circuit bars Exxon Valdez from operating The Berkeley Daily

Planet.

Headlines

2005q1 Coltoncompany.com. 2005-03-22.

Exxon

agrees to pay out 75 percent of Valdez damages Thomson Reuters.

Exxon

must pay US$480 million in interest over Valdez oil tanker spill The

Los Angeles Times.

Federal

Register / Vol. 75, No. 14 / Friday, January 22, 2010 / Notices

Daily

Vessel Casualty, Piracy & News Report

India

bars Alaska oil spill tanker Exxon Valdez BBS News.

New

setback for troubled ship as India bars beaching The National.

SC

gives green signal for beaching of US ship The Hindu. 31 July

2012.

23

years after one of history's worst oil spills, Exxon Valdez

'rests' in Gujarat Indian Express.

|

Name:

|

Oriental

Nicety

|

|

Owner:

|

Hong

Kong Bloom Shipping Ltd. (2008-present)

SeaRiver Maritime (1989-2008)

Exxon (1986-1989)

|

|

Port

of registry:

|

United

States (1986-2005)

Marshall Islands (2005-2008)

Panama

(2008-present)

|

|

Ordered:

|

1

August 1984

|

|

Builder:

|

National

Steel and Shipbuilding Company

San Diego, California

|

|

Laid

down:

|

24

July 1985

|

|

Launched:

|

14

October 1986

|

|

In

service:

|

11

December 1986-20 March 2012

|

|

Renamed:

|

Exxon

Valdez (1986-1989)

Exxon Mediterranean (1990-1993)

Sea River Mediterranean (1993-2005)

S/R Mediterranean (1993-2005)

Mediterranean (2005-2008)

Dong Fang Ocean (2008-2011)

Oriental Nicety (2011-present)

|

|

Refit:

|

30

June 1989

|

|

Identification:

|

Call

sign: 3EPL6

IMO number: 8414520

MMSI number: 356270000

|

|

Fate:

|

Sold

for scrap

|

|

General

characteristics

|

|

Class

& type:

|

VLCC

Oil tanker

|

|

Type:

|

ABS:

A1, Ore Carrier, AMS, ACCU, GRAB 25

|

|

Tonnage:

|

209,836 DWT

|

|

Displacement:

|

211,469

tons (214,862 metric tons)

|

|

Length:

|

300 m

(980 ft)

|

|

Beam:

|

51 m

(167 ft)

|

|

Draught:

|

20 m

(66 ft)

|

|

Deck

clearance:

|

7.183

to 7.442 m (23.57 to 24.42 ft)

|

|

Installed

power:

|

31,650

bhp (23,601 kW) at 79 rpm

|

|

Propulsion:

|

Eight-cylinder,

reversible, slow-speed Sulzer marine diesel engine.

|

|

Speed:

|

16.25

knots (30.10 km/h; 18.70 mph)

|

|

Capacity:

|

1.48

million barrels

(235,000 m³) of crude oil

|

|

Crew:

|

21

|

Solarnavigator

is designed to carry the Scorpion

anti pirate weapon. A fleet of such autonomous vessels could be the basis

of an international peacekeeping, and/or emergency rescue force.

The

navigation system that is being developed for SolarNavigator could have

prevented the sinking of the Costa Concordia. This might be of interest

to fleet operators.

|