When

I was a lad, I was drawn to the bright colors of wasps and their

fierce mandibles. I allowed wasps to nest in an old building, and was

stung several times for my troubles, after which I was so not keen to

provide shelter, but always did my best to live alongside wildlife. Then

one day I had to clear a wasp nest from a loft, because they were eating

the fabric of the building. I sprayed insect powder (nicotine) to kill

them, when out they came swarming at me. It was a bit like the 'Killer

Bees' movie and worrying at first. I braced myself to get stung again.

But I had a squash racquet to hand, and started swatting those that flew

at me. I killed half a dozen. Soon, instead of me dodging them, they

were frantically avoiding me. Role reversal. I guess that they knew they

were about to cop it. Whereas before I killed any of them, they probably

thought I was fair game. I soon dispatched the entire nest. It was a

turkey shoot. A wasp is no match for a squash

racquet.

DESCRIPTION

The term wasp is typically defined as any

insect of the order Hymenoptera and suborder Apocrita that is neither a bee nor an

ant. Almost every pest insect species has at least one wasp species that preys upon it or parasitizes it, making wasps critically important in natural control of their numbers, or natural biocontrol. Parasitic wasps are increasingly used in agricultural pest control as they prey mostly on pest insects and have little impact on crops.

The majority of wasp species (well over 100,000 species) are "parasitic" (technically known as parasitoids), and the ovipositor is used simply to lay eggs, often directly into the body of the host. The most familiar wasps belong to Aculeata, a "division" of Apocrita, whose ovipositors are adapted into a venomous sting, though a great many aculeate species do not sting. Aculeata also contains ants and bees, and many wasps are commonly mistaken for bees, and vice-versa. In a similar respect, insects called "velvet ants" (the family Mutillidae) are technically wasps.

The suborder Symphyta, known commonly as sawflies, differ from members of Apocrita by lacking a sting, and having a broader connection between the mesosoma and metasoma. In addition to this, Symphyta larvae are mostly herbivorous and "caterpillarlike", whereas those of Apocrita are largely predatory or parasitoids.

A much narrower and simpler but popular definition of the term wasp is any member of the aculeate family Vespidae, which includes (among others) the genera known in

North America as yellowjackets (Vespula and Dolichovespula) and hornets (Vespa); in many countries outside of the Western Hemisphere, the vernacular usage of wasp is even further restricted to apply strictly to

yellow-jackets (e.g., the "common wasp").

Categorization

The various species of wasps fall into one of two main categories: solitary wasps and social wasps. Adult solitary wasps live and operate alone, and most do not construct nests (below); all adult solitary wasps are fertile. By contrast, social wasps exist in colonies numbering up to several thousand individuals and build nests—but in some cases not all of the colony can reproduce. In some species, just the wasp queen and male wasps can mate, whilst the majority of the colony is made up of sterile female workers.

BIOLOGY

Genetics

In wasps, as in other Hymenoptera, sexes are significantly genetically different. Females have 2n number of chromosomes and come about from fertilized eggs. Males, in contrast, have a haploid (n) number of chromosomes and develop from an unfertilized egg. Wasps store sperm inside their body and control its release for each individual egg as it is laid; if a female wishes to produce a male egg, she simply lays the egg without fertilizing it. Therefore, under most conditions in most species, wasps have complete voluntary control over the sex of their offspring.

Anatomy and sex

Anatomically, there is a great deal of variation between different types of wasp. Like all insects, wasps have a hard exoskeleton covering their three main body parts. These parts are known as the head, mesosoma and metasoma. Wasps also have a constricted region joining the first and second segments of the abdomen (the first segment is part of the mesosoma, the second is part of the metasoma) known as the petiole. Like all insects, wasps have three sets of two legs. In addition to their compound eyes, wasps also have several simple eyes known as ocelli. These are typically arranged in a triangular formation just forward of an area of the head known as the vertex.

It is possible to distinguish between sexes of some wasp species based on the number of divisions on their antennae. For example, male

yellow-jacket wasps have 13 divisions per antenna, while females have 12. Males can in some cases be differentiated from females by virtue of having an additional visible segment in the metasoma. The difference between sterile female worker wasps and queens also varies between species but generally the queen is noticeably larger than both males and other females.

Wasps can be differentiated from bees, which have a flattened hind basitarsus. Unlike bees, wasps generally lack plumose hairs.

Diet

Generally, wasps are parasites or parasitoids as larvae, and feed on nectar only as adults. Many wasps are predatory, using other insects (often paralyzed) as food for their larvae. In parasitic species, the first meals are almost always derived from the host in which the larvae grow.

Several types of social wasps are omnivorous, feeding on a variety of fallen fruit, nectar, and carrion. Some of these social wasps, such as yellowjackets, may scavenge for dead insects to provide for their young. In many social species, the larvae provide sweet secretions that are consumed by adults. Adult male wasps sometimes visit flowers to obtain nectar to feed on in much the same manner as honey bees. Occasionally, some species, such as yellowjackets and, especially, hornets, invade honey bee nests and steal honey and/or brood.

ROLE in ECOSYSTEM

Pollination

While the vast majority of wasps play no role in pollination, a few species can effectively transport pollen and therefore contribute for the pollination of several plant species, being potential or even efficient

pollinators; in a few cases such as figs pollinated by fig wasps, they are the only pollinators, and thus they are crucial to the survival of their host plants.

Wasp parasitism

With most species, adult parasitic wasps themselves do not take any nutrients from their prey, and, much like bees, butterflies, and moths, those that do feed as adults typically derive all of their nutrition from nectar. Parasitic wasps are typically parasitoids, and extremely diverse in habits, many laying their eggs in inert stages of their host (egg or pupa), or sometimes paralyzing their prey by injecting it with venom through their ovipositor. They then insert one or more eggs into the host or deposit them upon the host externally. The host remains alive until the parasitoid larvae are mature, usually dying either when the parasitoids pupate, or when they emerge as adults.

Nesting habits

The type of nest produced by wasps can depend on the species and location. Many social wasps produce nests that are constructed predominantly from paper pulp. The kind of timber used varies from one species to another and this is what can give many species a nest of distinctive color. Social wasps also use other types of nesting material that become mixed in with the nest and it is common to find nests located near to plastic pool or trampoline covers incorporating distinct bands of color that reflect the inclusion of these materials that have simply been chewed up and mixed with wood fibres to give a unique look to the nest. Again each species of social wasp appears to favour its own specific range of nesting sites. D. media and D. sylvestris prefer to nest in trees and shrubs, others like V. germanica like to nest in cavities that include holes in the ground, spaces under homes, wall cavities or in lofts. By contrast solitary wasps are generally parasitic or predatory and only the latter build nests at all. Unlike honey bees, wasps have no wax producing glands. Many instead create a paper-like substance primarily from wood pulp. Wood fibers are gathered locally from weathered wood, softened by chewing and mixing with saliva. The pulp is then used to make combs with cells for brood rearing. More commonly, nests are simply burrows excavated in a substrate (usually the soil, but also plant stems), or, if constructed, they are constructed from mud.

Solitary wasps

The nesting habits of solitary wasps are more diverse than those of social wasps. Mud daubers and pollen wasps construct mud cells in sheltered places typically on the side of walls. Potter wasps similarly build vase-like nests from mud, often with multiple cells, attached to the twigs of trees or against walls. Most other predatory wasps burrow into soil or into plant stems, and a few do not build nests at all and prefer naturally occurring cavities, such as small holes in wood. A single egg is laid in each cell, which is then sealed, so there is no interaction between the larvae and the adults, unlike in social wasps. In some species, male eggs are selectively placed on smaller prey, leading to males being generally smaller than females.

Social wasps

The nests of some social wasps, such as hornets, are first constructed by the queen and reach about the size of a walnut before sterile female workers take over construction. The queen initially starts the nest by making a single layer or canopy and working outwards until she reaches the edges of the cavity. Beneath the canopy she constructs a stalk to which she can attach several cells; these cells are where the first eggs will be laid. The queen then continues to work outwards to the edges of the cavity after which she adds another tier. This process is repeated, each time adding a new tier until eventually enough female workers have been born and matured to take over construction of the nest leaving the queen to focus on reproduction. For this reason, the size of a nest is generally a good indicator of approximately how many female workers there are in the colony and some hornets' nests eventually grow to the size of beach balls. Social wasp colonies often have populations of between three and ten thousand female workers at maturity, although a small proportion of nests are seen on a regular basis that are over three feet across and potentially contain upwards of twenty thousand workers and at least one queen. What has also been seen are nests close to one another at the beginning of the year growing quickly and merging with one another to create nests with tens of thousands of

workers. Some related types of paper wasp do not construct their nests in tiers but rather in flat single combs.

Social wasp reproductive cycle (temperate species only)

Wasps do not reproduce via mating flights like bees. Instead social wasps reproduce between a fertile queen and male wasp; in some cases queens may be fertilized by the sperm of several males. After successfully mating, the male's sperm cells are stored in a tightly packed ball inside the queen. The sperm cells are kept stored in a dormant state until they are needed the following spring. At a certain time of the year (often around autumn), the bulk of the wasp colony dies away, leaving only the young mated queens alive. During this time they leave the nest and find a suitable area to hibernate for the winter.

First stage

After emerging from hibernation during early summer, the young queens search for a suitable nesting site. Upon finding an area for their colony, the queen constructs a basic wood fiber nest roughly the size of a walnut into which she will begin to lay eggs.

Second stage

The sperm that was stored earlier and kept dormant over winter is now used to fertilize the eggs being laid. The storage of sperm inside the queen allows her to lay a considerable number of fertilized eggs without the need for repeated mating with a male wasp. For this reason a single queen is capable of building an entire colony by herself. The queen initially raises the first several sets of wasp eggs until enough sterile female workers exist to maintain the offspring without her assistance. All of the eggs produced at this time are sterile female workers who will begin to construct a more elaborate nest around their queen as they grow in number.

Third stage

By this time the nest size has expanded considerably and now numbers between several hundred and several thousand wasps. Towards the end of the summer, the queen begins to run out of stored sperm to fertilize more eggs. These eggs develop into fertile males and fertile female queens. The male drones then fly out of the nest and find a mate thus perpetuating the wasp reproductive cycle. In most species of social wasp the young queens mate in the vicinity of their home nest and do not travel like their male counterparts do. The young queens will then leave the colony to hibernate for the winter once the other worker wasps and founder queen have started to die off. After successfully mating with a young queen, the male drones die off as well. Generally, young queens and

drones from the same nest do not mate with each other; this ensures more genetic variation within wasp populations, especially considering that all members of the colony are theoretically the direct genetic descendants of the founder queen and a single male drone. In practice, however, colonies can sometimes consist of the offspring of several male drones. Wasp queens generally (but not always) create new nests each year, probably because the weak construction of most nests render them uninhabitable after the winter.

Unlike honey bee queens, wasp queens typically live for only one year. Also queen wasps do not organize their colony or have any raised status and hierarchical power within the social structure. They are more simply the reproductive element of the colony and the initial builder of the nest in those species which construct nests.

Social wasp caste structure

Not all social wasps have castes that are physically different in size and structure. For example, in many polistine paper wasps and stenogastrines, the castes of females are determined behaviorally, through dominance interactions, rather than having caste predetermined. All female wasps are potentially capable of becoming a colony's queen and this process is often determined by which female successfully lays eggs first and begins construction of the nest. Evidence suggests that females compete amongst each other by eating the eggs of other rival females. The queen may, in some cases, simply be the female that can eat the largest volume of eggs while ensuring that her own eggs survive (often achieved by laying the most). This process theoretically determines the strongest and most reproductively capable female and selects her as the queen. Once the first eggs have hatched, the subordinate females stop laying eggs and instead forage for the new queen and feed the young; that is, the competition largely ends, with the "losers" becoming workers, though if the dominant female dies, a new hierarchy may be established with a former "worker" acting as the replacement queen. Polistine nests are considerably smaller than many other social wasp nests, typically housing only around 250 wasps, compared to the several thousand common with yellowjackets, and stenogastrines have the smallest colonies of all, rarely with more than a dozen wasps in a mature colony.

Where to find them

Wasps build their nests in a variety of places, often choosing sunny spots. Nests are commonly located in holes underground, along riverbanks or small hillocks, attached to the side of walls, trees or plants, or underneath floors or eaves of houses. Wasp nests are most easily found on sunny days at dawn or dusk as the low light levels make it easier to spot the Wasps flying in and out of their nests. Wasps will attack and sting humans, particularly if threatened, so care should be taken around Wasps and their nests. Wasp nests found in dangerous places (such as in houses or in commonly used public spaces) should be reported to the local council or pest control service for removal.

Common families

Agaonidae – fig wasps

Chalcididae

Chrysididae – cuckoo wasps

Crabronidae – sand wasps and relatives, e.g. the Cicada killer wasp.

Cynipidae – gall wasps

Encyrtidae

Eulophidae

Eupelmidae

Ichneumonidae, and Braconidae

Mutillidae – velvet ants

Mymaridae – fairyflies

Pompilidae – spider wasps

Pteromalidae

Scelionidae

Scoliidae – scoliid wasps

Sphecidae – digger wasps

Tiphiidae – flower wasps

Torymidae

Trichogrammatidae

Vespidae – Common Wasp, yellowjackets, hornets, paper wasps (umbrella), potter wasps, pollen wasps

NEW

SPECIES - March 2012

A new and unusual wasp species has been discovered during an expedition to the

Indonesian island of

Sulawesi. It was independently also found in the insect collections of the Museum für Naturkunde in

Berlin, where it was awaiting discovery since the 1930s, when it had been collected on Sulawesi. The new species is pitch-black, has an enormous body size, and its males have long, sickle-shaped jaws. The findings have now been described in the open access journal ZooKeys.

The species belongs into the digger wasp family, which is a diverse group of wasps with several thousands of species known from all over the world. Female digger wasps search for other insects as prey for their young and paralyze the prey by stinging it. Prey selection is often species specific, but the prey of the new species is unknown. With its unusual body size and the male's jaws, the new species differs from all known related digger wasps, so much so that it was placed in a new genus of its own, Megalara.

The new genus name is a combination of the Greek Mega, meaning large, and the ending of Dalara, a related wasp genus. Lynn Kimsey (UC Davis) and Michael Ohl (Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin), who discovered the giant wasp simultaneously and have worked on it in collaboration, named the species after Garuda, the national symbol of Indonesia, a part-human, part-eagle mythical creature known as the King of Birds in Hindu mythology.

Since this species has never been observed alive, nothing is known about its biology or behavior. The males of Megalara garuda are distinctly larger than the females, and bear very long jaws. As can be deduced from other insects with large jaws, it is likely that the males hold the females with it during copulation. It is also possible that they use the jaws for defense.

http://phys.org/news/2012-03-megalara-garuda-king-wasps.html

This is a a close view of the enormous jaws of the male wasps.

Credit: Dr. Lynn Kimsey, Dr. Michael Ohl

NEW SPECIES named after Wright State entomologist January 2, 2013

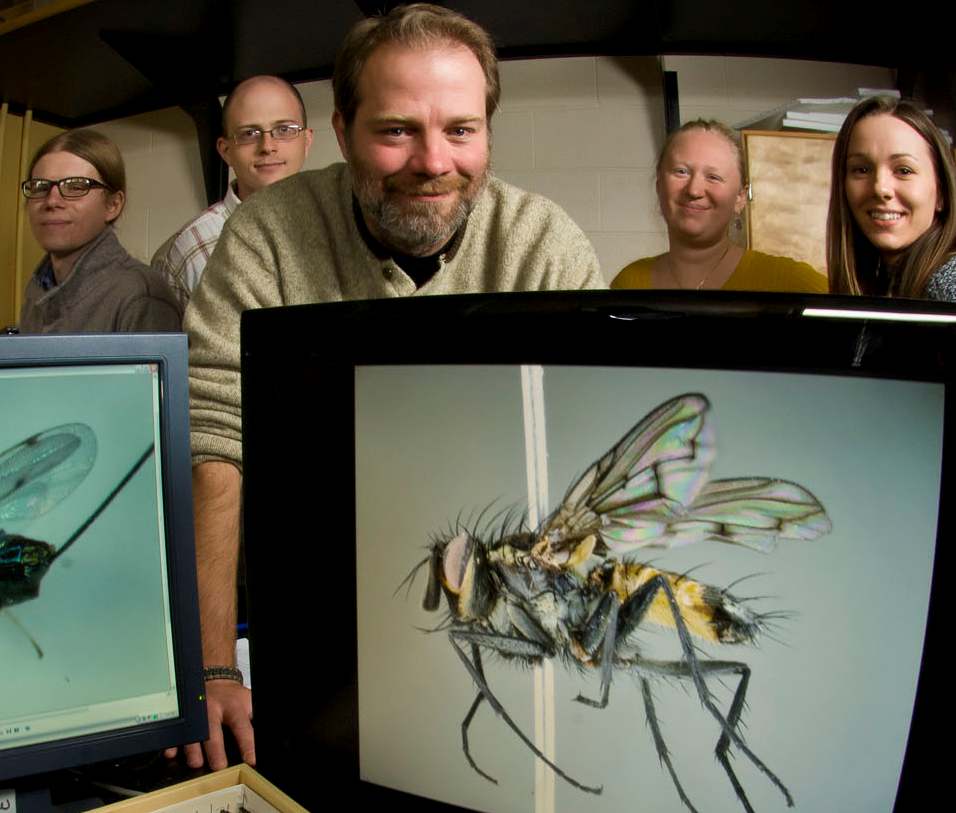

Biology professor John Stireman flanked by students in his lab: (left to right) Zach Burington, Dan Davis, Stireman, Karen Pedersen and Tiffany Brown. A strip of masking tape under his name on the office door identifies him as "Lord of the Flies." With a salt-and-pepper beard and countless jungle jaunts under his belt, he's become the Indiana Jones of insects at Wright State. And now, he has a wasp named after him. A newly described species of braconid wasp has been officially christened Ilatha stiremani after Wright State entomologist John Stireman.

The relatively large, colorful wasp was named in a scientific paper in honor of Stireman for his research help in identifying and providing information on tachinids, a large family of flies. Stireman's role was to examine the pupa—which precedes the adult stage—of flies that were carrying the newly identified parasitic wasp. "I've never had a species named after me before; it is an honor to be recognized in that way. I have friends who have species named after them, so now I feel better," Stireman said with a smile. However, he downplays the honor, saying it is not that unusual for newly identified species of insects to be named after someone and that there continues to be plenty of opportunity. "There are hundreds of new species pinned in drawers in museums, but there are not enough knowledgeable people to look at those things," he said. Don Cipollini, Ph.D., director of Environmental Sciences, said it is a tremendous honor to have one's name immortalized in the scientific name of a species. "John was honored because of his standing as one of the world's experts on tachinid flies, a host for this parasitic wasp," said Cipollini. "It is an honor for Wright State to have such well-respected researchers among its faculty." Stireman has been heavily involved with researchers at other universities in a National Science Foundation funded project to take an inventory of the biodiversity in the Andes Mountains of Ecuador.

The project has taken Stireman to Ecuador a half dozen times, working largely in elevations of between 7,000 and 8,000 feet. "We go into these cloud

forests that are super-diverse—really diverse plant communities, really diverse insect communities—but we really know nothing about most of the species," he said. "A lot of the species are undescribed. Even the ones that we do know exist, we don't know anything about them—what they eat, what eats them. You can use that information to understand the whole food web of an ecosystem." Stireman's love of biology and insects developed as he was growing up in Utah. His father studied mosquitoes as a graduate student, and Stireman spent a lot of time hiking and backpacking. "You're out there and you're seeing things and you want to know what they are," he said. Stireman majored in biology at the University of Utah and obtained his doctorate in ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, where he worked on an independent project that focused on flies. He did post doctorate work at Tulane and Iowa State universities, then landed a teaching job at Wright State in 2005.

http://phys.org/news/2013-01-species-wasp-wright-state-entomologist.html