|

FBI

|

||||||||

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | BOOKS | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | NEWS | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT |

||||||||

|

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is a federal criminal investigative, intelligence agency, and the primary investigative arm of the United States Department of Justice (DOJ). At present, the FBI has investigative jurisdiction over violations of more than 200 categories of federal crimes and thus has the broadest investigative authority of any U.S. federal law enforcement agency. The motto of the bureau is "Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity."

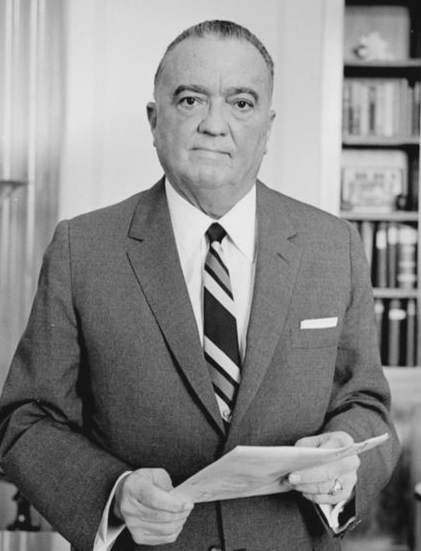

Starting in 1908 as the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) it did not rename to the Federal Bureau of Investigation until 1935. J. Edgar Hoover, the first FBI Director, continuing his tenure from the BOI, was the longest serving FBI director to date. He also is responsible for many of the advancements and changes he made as the FBI director for it to become a leading agency in the world. The J. Edgar Hoover building, FBI Academy, and the Criminal Justice Information Services Complex serve as the main support offices for each of the field offices that are located throughout the country.

As one of the primary investigative and intelligence agencies of the United States, its collection and publications of crime statistics keeps the public aware of crime rates and the types of crime that has been committed. Before the September 11, 2001 attacks, the FBI only had a marginal role in trying to prevent crime before it happens. Now the FBI actively attacks potential threats before they can take place.

Overall mission

The mission of the FBI is to protect and defend the United States against terrorist and foreign threats, to uphold and enforce the criminal laws of the United States, and to provide leadership and criminal justice services to federal, state, municipal, and international agencies and partners. Title 28 of the United States Code (U.S. Code), Section 533, authorizes the Attorney General to "appoint officials to detect... crimes against the United States," and other federal statutes give the FBI the authority and responsibility to investigate specific crimes.

Information obtained through an FBI investigation is presented to the appropriate U.S. Attorney or Department of Justice (DOJ) official, who decides if prosecution or other action is warranted.

Currently, the FBI top investigative priorities have been assigned to these areas:

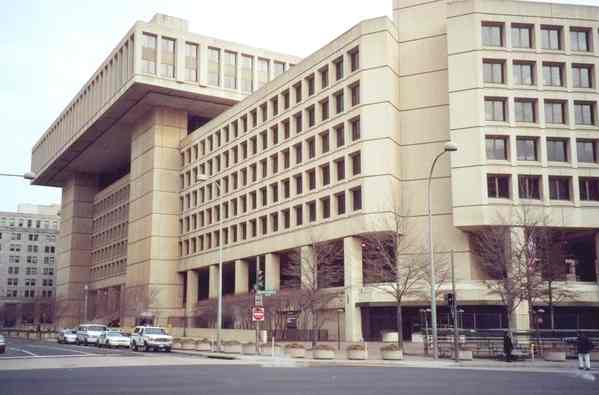

J. Edgar Hoover Building, FBI Headquarters

As of June 2006, the FBI's top priority is counter-terrorism. The second priority is counterintelligence. The USA PATRIOT Act granted the FBI increased powers, especially in wiretapping and monitoring of Internet activity. One of the most controversial provisions of the act is the so-called "sneak and peek" provision, granting the FBI powers to search a house while the residents are away, and not requiring them to notify the residents for several weeks afterwards. Under the PATRIOT Act's provisions the FBI also resumed inquiring into the library records of those who are suspected of terrorism (something it had supposedly not done since the 1970s). The third and fourth priorities are cyber crimes and public corruption. The cyber crimes category includes distribution of computer viruses and other malicious code. It also includes online distribution of child pornography among other crimes.

The FBI continues its historic mission of fighting organized crime. The FBI targets the organization behind the crime rather than individual criminals committing individual crimes. The FBI's chief tool against organized crime is the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. The FBI is also charged with the responsibility of enforcing compliance of the United States Civil Rights Act of 1964 and investigating violations of the act in addition to prosecuting such violations with the United States Department of Justice (DOJ). The FBI also shares concurrent jurisdiction with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the enforcement of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

History

The FBI originated from a force of Special Agents created on July 26, 1908, by Attorney General Charles Joseph Bonaparte during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. At first it was named the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and it did not become the FBI until 1935.

On July 1, 1932, the Bureau was renamed the United States Bureau of Investigation. One year later on July 1, 1933, it was linked with the Bureau of Prohibition and became known as the Division of Investigation. Finally, in 1935, the bureau was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. J. Edgar Hoover, who served as a BOI director and the FBI first director, served for forty-eight years. After Hoover's death, the FBI imposed a policy limiting the tenure of future FBI directors to a maximum of ten years. The Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory (now known as the FBI Laboratory) officially opened on November 24, 1932 in which Hoover was a major force behind it opening. Hoover had a major say in most of the cases and projects the FBI handled all the way up to his death. During the 1930s, the agency played a prominent role in apprehending a number of well-known criminals who had conducted kidnappings, robberies and murders throughout the nation. These included John Dillinger, "Baby Face" Nelson, Kate "Ma" Barker, Alvin Karpis and George "Machine Gun" Kelly. It also played a decisive role in reducing the scope and influence of the Ku Klux Klan. Through the work of Edwin Atherton, the FBI claimed success in apprehending an entire army of Mexican neo-revolutionaries along the California border in the 1920's.

Beginning with the 1940s and continuing into the 1970s, the agency investigated cases of espionage against the United States and its allies. Eight Nazi agents who had planned sabotage operations against American targets were arrested, six of whom were executed (Ex parte Quirin). Also during this time, a US joint FBI/military code breaking effort (Venona), "broke" Soviet diplomatic and intelligence communications codes, allowing the US and British governments to read Soviet communications. This effort confirmed the existence of Americans working in the United States for Soviet intelligence. Hoover was administering this project and did not even notify the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) until 1952. FBI officials showed increased alarm about civil rights leaders who were perceived to be overly militant. In 1956, for example, Hoover took the rare step of sending an open letter denouncing Dr. T.R.M. Howard, a civil rights leader, surgeon, and wealthy entrepreneur in Mississippi who had criticized FBI inaction in solving recent murders of George W. Lee, Emmett Till, and other blacks in the South.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the FBI carried out controversial domestic surveillance in an operation called COINTELPRO. It aimed at investigating and disrupting dissident political organizations within the United States, including militant organizations and non-violent movements, including the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a leading civil rights organization. Martin Luther King, Jr. was a frequent target of investigation. The FBI found no evidence of any crime, but attempted to use tapes of King involved in sexual activity for blackmail. Washington Post journalist Carl Rowan 1991 memoirs, asserted that the FBI had sent at least one anonymous letter to King encouraging him to commit suicide. When President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed, the jurisdiction fell to the local police departments, but then President Lyndon B. Johnson directed the FBI to take over the investigation. To ensure that there would never be any more confusion over who would handle homicides at the federal level, Congress passed a law that put investigations of deaths of federal officials within FBI jurisdiction.

After the RICO act took effect and the FBI started investigating the former Prohibition organized groups, which had by now become fronts for crime in major cities and even small towns. All of the FBI work was done undercover and from within these organizations using the provisions provided in the RICO act, these groups were dismantled. Although Hoover initially doubted the existence of a close-knit organized crime network in the United States, the bureau later conducted operations against known organized crime syndicates and families, including those headed by Sam Giancana and John Gotti. The RICO act is still used today for all organized crime and any individuals that might fall under the act.

J. Edgar Hoover, FBI Director (1924-1972)

In 1984 the FBI formed an elite SWAT team to help with problems that might arise at the 1984 Summer Olympics including terrorism and major-crime. The formation of the team arose from the 1972 Summer Olympics at Munich, Germany when terrorists murdered Israeli Athletes. The team was named Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) and acts as the FBI lead for SWAT related procedures and all Counter-Terrorism cases. Also formed in 1984 was the Computer Analysis and Response Team (CART) that would investigate all matters into and including gathering evidence. During the end of the 1980s and the early part of the 1990s, saw the reassigning over 300 agents from foreign counter-intelligence duties to violent crime and making violent crime the 6th national priority. But with reduced cuts to other departments that have already been established, bearing in mind that terrorism was no longer a threat due to the Cold war ending, the FBI became a tool by local police forces for finding and hunting down fugitives that crossed state lines which was an established federal felony at the time. The FBI Laboratory also helped in their development due to DNA testing just like they do with their fingerprinting system in 1924.

Between 1993 and 1996 the FBI however increased its terrorism role in wake of the first 1993 World Trade Center Bombing in New York, New York, bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building (1995) in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and the arrest of the UNABOMBER in 1996. Improvements in their technology and Laboratory skills paid off when all three of these cases were successfully prosecuted, but the FBI would also have a string of public outcry during this time, which still haunts the agency today. Once the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) of 1994, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPA) of 1996, and the Economic Espionage Act, also in 1996, were passed in congress the FBI followed suit also upgrading their technological skills in 1998, just as it did in 1991 with the CART team. Computer Investigations and Infrastructure Threat Assessment Center (CITAC) and the National Infrastructure Protection Center (NIPC) were created to deal with the increased growth of the World Wide Web related incidents from virus, worms, and other malicious programs that might cause havoc on the US internet structure. This helped the FBI also conduct court-authorized electronic surveillance in major investigations affecting public safety and national security in the face of telecommunications advancement.

With months after the September 11th, 2001 attacks, current FBI Director Robert Mueller, who was only sworn in three days before the attacks, called for a re-engineering of FBI structure and operations. In turn he made every federal crime a top priority, including prevention of terrorist attacks, countering foreign intelligence operations, addressing cyber crime-based attacks, other high-technology crimes, protecting civil rights, combating public corruption, organized crime, white-collar crime, and major acts of violent crime all of which now fall under the top investigative priorities of the FBI mission.

Organization

The FBI is headquartered at the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington, D.C., with 56 field offices in major cities across the United States. The FBI also maintains over 400 resident agencies across the United States, as well as over 50 legal attachés at United States embassies and consulates. Many specialized FBI functions are located at facilities in Quantico, Virginia, as well as in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

The FBI Laboratory, established with the formation of the BOI, did not appear in the J. Edgar Hoover Building until its completion in 1974. The lab serves as the primary lab for most DNA, biological, and physical work. Public tours of FBI headquarters ran through the FBI laboratory work space before the move to the J. Edgar Hoover Building. The services the lab conducts include Chemistry, Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), Computer Analysis and Response, DNA Analysis, Evidence Response, Explosives, Firearms and Toolmarks, Forensic Audio, Forensic Video, Image Analysis, Forensic Science Research, Forensic Science Training, Hazardous Materials Response, Investigative and Prospective Graphics, Latent Prints, Materials Analysis, Questioned Documents, Racketeering Records, Special Photographic Analysis, Structural Design, and Trace Evidence. The services of the FBI Laboratory are used by many state, local, and international agencies free of charge. The lab also maintains a second lab at the FBI Academy.

The FBI Academy, located in Quantico, Virginia, is home to the communications and computer laboratory the FBI utilizes. It also serves at the main places where new agents are sent to become FBI Special Agents. Going through the eighteen week course is a must for every Special Agent. It was first opened for use in 1972 on 385 acres (1.6 km²) of woodland. The Academy also servers as a classroom for state and local law enforcement agencies who are invited onto the premiere law enforcement training center. The FBI units that reside at Quantico are the Field and Police Training Unit, Firearms Training Unit, Forensic Science Research and Training Center, Technology Services Unit (TSU), Investigative Training Unit, Law Enforcement Communication Unit, Leadership and Management Science Unit's (LSMU), Physical Training Unit, New Agents' Training Unit (NATU), Practical Applications Unit (PAU), and the Investigative Computer Training Unit.

The Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division, located in Clarksburg, West Virginia. It is the youngest division of the FBI only being formed in 1991 and opening in 1995. The complex itself is the length of three football fields. Its purpose is to provide a main repository for information. Under the roof of the CJIS are the programs for the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR), Fingerprint Identification, Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS), NCIC 2000, and the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). Many state and local agencies use these systems as a source for their own investigations and also contribute to the database using secure communications. FBI provides these tools of sophisticated identification and information services to local, state, federal, and international law enforcement agencies.

The FBI often works in conjunction with other Federal agencies, including the United States Coast Guard and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) in seaport security, and the National Transportation Safety Board in investigating airplane crashes and other critical incidents. The FBI has the authority to take the charge of any federal investigation because of the broad power the FBI carries. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is the only other agency with the closest amount of investigative power. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks the FBI always maintains a role in most federal criminal investigations.

Edgar Hoover as director

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing into the 1970s, the Bureau investigated cases of espionage against the United States and its allies. Eight Nazi agents who had planned sabotage operations against American targets were arrested, and six were executed (Ex parte Quirin) under their sentences. Also during this time, a joint US/UK code-breaking effort (Venona)—with which the FBI was heavily involved—broke Soviet diplomatic and intelligence communications codes, allowing the US and British governments to read Soviet communications. This effort confirmed the existence of Americans working in the United States for Soviet

intelligence. Hoover was administering this project but failed to notify the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) until 1952. Another notable case is the arrest of Soviet spy Rudolf Abel in

1957. The discovery of Soviet spies operating in the US allowed Hoover to pursue his longstanding obsession with the threat he perceived from the American Left, ranging from Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) union organizers to American liberals.

During the 1950s and 1960s, FBI officials became increasingly concerned about the influence of civil rights leaders, whom they believed had communist ties or were unduly influenced by them. In 1956, for example, Hoover sent an open letter denouncing Dr. T.R.M. Howard, a civil rights leader, surgeon, and wealthy entrepreneur in Mississippi who had criticized FBI inaction in solving recent murders of George W. Lee, Emmett Till, and other blacks in the

South. The FBI carried out controversial domestic surveillance in an operation it called the COINTELPRO, which was short for

"COunter-INTELligence PROgram." It was to investigate and disrupt the activities of dissident political organizations within the United States, including both militant and non-violent organizations. Among its targets was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a leading civil rights organization with clergy

leadership.

When President John F. Kennedy was shot and killed, the jurisdiction fell to the local police departments until President Lyndon B. Johnson directed the FBI to take over the

investigation. To ensure clarity about responsibility for investigation of homicides of federal officials, Congress passed a law that put investigations of deaths of federal officials within FBI jurisdiction.

In response to organized crime, on August 25, 1953, the FBI created the Top Hoodlum Program. The national office directed field offices to gather information on mobsters in their territories and to report it regularly to Washington for a centralized collection of intelligence on

racketeers. After the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO Act, took effect, the FBI began investigating the former Prohibition-organized groups, which had become fronts for crime in major cities and small towns. All of the FBI work was done undercover and from within these organizations, using the provisions provided in the RICO Act. Gradually the agency dismantled many of the groups. Although Hoover initially denied the existence of a National Crime Syndicate in the United States, the Bureau later conducted operations against known organized crime syndicates and families, including those headed by Sam Giancana and John Gotti. The RICO Act is still used today for all organized crime and any individuals who might fall under the Act.

Special FBI teamsIn 1984, the FBI formed an elite

unit to help with problems that might arise at the 1984 Summer Olympics to be held in Los Angeles, particularly terrorism and major-crime. This was a result of the 1972 Summer Olympics at Munich, Germany, when terrorists murdered the Israeli athletes. Named Hostage Rescue Team (HRT), it acts as the FBI lead for a national SWAT team in related procedures and all counter-terrorism cases. Also formed in 1984 was the Computer Analysis and Response Team

(CART).

Within months of the September 11 attacks in 2001, FBI Director Robert Mueller, who had been sworn in a week before the attacks, called for a re-engineering of FBI structure and operations. He made countering every federal crime a top priority, including the prevention of terrorism, countering foreign intelligence operations, addressing cyber security threats, other high-tech crimes, protecting civil rights, combating public corruption, organized crime, white-collar crime, and major acts of violent

crime.

LINKS

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|

||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2012 Max Energy Limited, an environmental educational charity working hard for world peace. The names Solar Navigator™,Blueplanet Ecostar BE3™ and Utopia Tristar™ are trademarks. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. |

||||||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEPLANET | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS | SOLARNAVIGATOR |