|

VIKINGS

|

|

The term Viking though used to denote ship-borne explorers, traders and warriors, is actually a verb describing the acts of the Danes who originated in Denmark and raided the coasts of the British Isles, France and other parts of Europe from the late 8th century to the 11th century. This period of European history (generally dated to 793–1066) is often referred to as the Viking Age. It may also be used to denote the entire populations of these countries and their settlements elsewhere.

Famed for their navigation ability and long ships, Vikings in a few hundred years colonized the coasts and rivers of Europe, the islands of Shetland, Orkney, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, and for a short while also Newfoundland circa 1000 [1], while still reaching as far south as North Africa, east into Russia and to Constantinople for raiding and trading. Viking voyages grew less frequent with the introduction of Christianity to Scandinavia in the late 10th and 11th century. The Viking Age is often considered to have ended with the battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.

Viking Longship Oseberg

The word viking was introduced to the English language with romantic connotations in the 18th century. In the current Scandinavian languages the term viking is applied to the people who went away on viking expeditions, be it for raiding or trading. In English it has become common to use it to refer to the Viking Age Scandinavians in general. The medieval Scandinavian population is also referred to as Norse.

The Viking Age

The period of North Germanic expansion, usually taken to last from the earliest recorded raids in the 790s until the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, is commonly called the Viking Age. The Vikings may be seen as late joiners in the Migrations period, and thus the period links Late Antiquity with the high Middle Ages. Geographically, a "Viking Age" may be assigned not only to the Scandinavian lands (modern Denmark, and southern Norway and Sweden), but also to territories under North Germanic dominance, mainly the Danelaw, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Ireland. Contemporary with the European Viking Age, the Byzantine Empire experienced the greatest period of stability (circa 800–1071) it would enjoy after the initial wave of Arab conquests in the mid-7th century.

Viking navigators also opened the road to new lands to the north and to the west, resulting in the colonization of Shetland, Orkney, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, and even an expedition to, and a short-lived settlement in, Newfoundland circa 1000.

During three centuries, Vikings appeared along the coasts and rivers of Europe, as traders, but also as raiders, and even as settlers. From 839, there were Varangian mercenaries in Byzantine service (most famously Harald Hardrada, who campaigned in North Africa and Jerusalem in the 1030s). Important trading ports during the period include Birka, Hedeby, Kaupang, Jorvik, Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod and Kiev. Generally speaking, the Norwegians expanded to the north and west, the Danes to England and France, settling in the Danelaw, and the Swedes to the east. But the three nations were not yet clearly separated, and still united by the common Old Norse language. The names of Scandinavian kings are known only for the later part of the Viking Age, and only after the end of the Viking Age did the separate kingdoms acquire a distinct identity as nations, which went hand in hand with their christianization. Thus it may be noted that the end of the Viking Age (9th–11th century) for the Scandinavians also marks the start of their relatively brief Middle Ages.

Decline

After trade and settlement, cultural impulses flowed from the rest of europe. Christianity had an early and growing presence in Scandinavia, and with the rise of centralized authority along with a stiffening of coastal defense in the areas the vikings preyed upon, the Viking raids became more risky and less profitable. With the rise of kings and greate nobles and a quasi - feudal system in Scandinavia, they ceased entirely - in the 11th century the scandinavians are frequently chronicled as combating "vikings" from the baltic, which would eventually lead to danish and swedish participation in the baltic crusades

Composite image made from several sides of the Ledberg Runestone having illustrations of what probably are Varangians in the Byzantine Empire and a Byzantine ship

Historical records

The earliest date given for a Viking raid is 787 when, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a group of men from Norway sailed to Portland, in Dorset. There, they were mistaken for merchants by a royal official, and they murdered him when he tried to get them to accompany him to the king's manor to pay a trading tax on their goods. The next recorded attack, dated June 8, 793, was on the monastery at Lindisfarne—the "Holy Island"—on the east coast of England. For the next 200 years, European history is filled with tales of Vikings and their plundering.

Vikings exerted influence throughout the coastal areas of Ireland and Scotland, and conquered and colonized large parts of England. Wales also saw large-scale Viking settlements on its coast; the modern day city of Swansea takes its name from Sweyne the Viking who was shipwrecked at modern day Swansea Bay; neighbouring Gower Peninsula has many place names of Norse origin (such as Worms Head, worm is the Norse word for dragon, as the Vikings believed that the serpent shaped island was a sleeping dragon). Twenty miles west of Cardiff on the Vale of Glamorgan coast is the semi-flooded island of Tusker Rock which takes it names from Tuska the Viking whose people semi-colonised the fertile lands of the Vale of Glamorgan. They travelled up the rivers of France and Spain, and gained control of areas in Russia and along the Baltic coast. Stories tell of raids in the Mediterranean and as far east as the Caspian Sea.

Significantly, the Celtic nations of Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Cornwall, during their battles against the Anglo-Saxons, decided to ally with the Vikings against the Saxons. Possibly as a result, the modern-day Celtic nations of Britain, in particular the cities of Cardiff and Swansea, and in Ireland the cities of Cork and Dublin, have a certain pride in what is perceived as "Viking ancestry".

Adam of Bremen records in his book Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum, (volume four):

Viking raids in Iberia

By the mid 9th century, though apparently not before (Fletcher 1984, ch. 1, note 51), there were Viking attacks on the coastal Kingdom of Asturias in the far northwest of the peninsula, though historical sources are too meagre to assess how frequent or how early raiding was. By the reign of Alfonso III Vikings were stifling the already weak threads of sea communications that tied Galicia (a province of the Kingdom) to the rest of Europe. Richard Fletcher attests raids on the Galician coast in 844 and 858: "Alfonso III was sufficiently worried by the threat of Viking attack to establish fortified strong points near his coastline, as other rulers were doing elsewhere." In 968 Bishop Sisnando of Compostela was killed, the monastery of Curtis was sacked, and measures were ordered for the defence of the inland town of Lugo. After Tuy was sacked early in the 11th century, its bishopric remained vacant for the next half-century. Ransom was a motive for abductions: Fletcher instances Amarelo Mestáliz, who was forced to raise money on the security of his land in order to ransom his daughters who had been captured by the Vikings in 1015. Bishop Cresconio of Compostela (ca. 1036–66) repulsed a Viking foray and built the fortress at Torres del Oeste (Council of Catoira) to protect Compostela from the Atlantic approaches.

In the Islamic south, the first navy of the Emirate was called into being after the humiliating Viking ascent of the Guadalquivir, 844, and was tested in repulsing Vikings in 859. Soon the dockyards at Seville were extended, it was employed to patrol the Iberian coastline under the caliphs Abd al-Rahman III (912–61) and Al-Hakam II (961–76). By the next century piracy from Saracens superseded the Viking scourge.

Rune stones

Many rune stones in Scandinavia record the names of participants in Viking expeditions. Other rune stones mention men who died on Viking expeditions, among them the around 25 Ingvar stones in the Mälardalen district of Sweden erected to commemorate members of a disastrous expedition into present-day Russia in the early 11th century. The rune stones are important sources in the study of the entire Norse society and early medieval Scandinavia, not only of the 'Viking' segment of the population (Sawyer, P H: 1997).

Icelandic sagas

Norse mythology, Norse sagas and Old Norse literature tell us about their religion through tales of heroic and mythological heroes. However, the transmission of this information was primarily oral, and we are reliant upon the writings of (later) Christian scholars, such as the Icelanders Snorri Sturluson and Sćmundr fróđi, for much of this. Many of these sagas were written in Iceland, and most of them, even if they had no icelandic provenience, was preserved there after the middle ages due to the Icelanders' continued interest in norse literature and law codes.

Vikings in those sagas are described as if they often struck at accessible and poorly defended targets, usually with impunity. The sagas state that the Vikings built settlements and were skilled craftsmen and traders.

Etymology

The etymology of "Viking" is somewhat vague. One path might be from the Old Norse word, vík, meaning "bay," "creek," or "inlet," and the suffix -ing, meaning "coming from" or "belonging to." Thus, viking would be a 'person of the bay', or "bayling" for lack of a better word. In Old Norse, this would be spelled víkingr. Later on, the term, viking, became synonymous with "naval expedition" or "naval raid", and a víkingr was a member of such expeditions. A second etymology suggested that the term is derived from Old English, wíc, ie. "trading city" (cognate to Latin vicus, "village").

The word viking appears on several rune stones found in Scandinavia. In the Icelanders' sagas, víking refers to an overseas expedition (Old Norse farar i vikingr "to go on an expedition"), and víkingr, to a seaman or warrior taking part in such an expedition.

In Old English, the word wicing appears first in the Anglo-Saxon poem, "Widsith", which probably dates from the 9th century. In Old English, and in the writings of Adam von Bremen, the term refers to a pirate, and is not a name for a people or a culture in general.

The word disappeared in Middle English, and was reintroduced as viking during 18th century Romanticism (the "Viking revival"), with heroic overtones of "barbarian warrior" or noble savage. During the 20th century, the meaning of the term was expanded to refer not only to the raiders, but also to the entire period; it is now, somewhat confusingly, used as a noun both in the original meaning of raiders, warriors or navigators, and to refer to the Scandinavian population in general. As an adjective, the word is used in expressions like "Viking age," "Viking culture," "Viking colony," etc., generally referring to medieval Scandinavia.

The Gokstad viking ship at display in Oslo, Norway

Ships

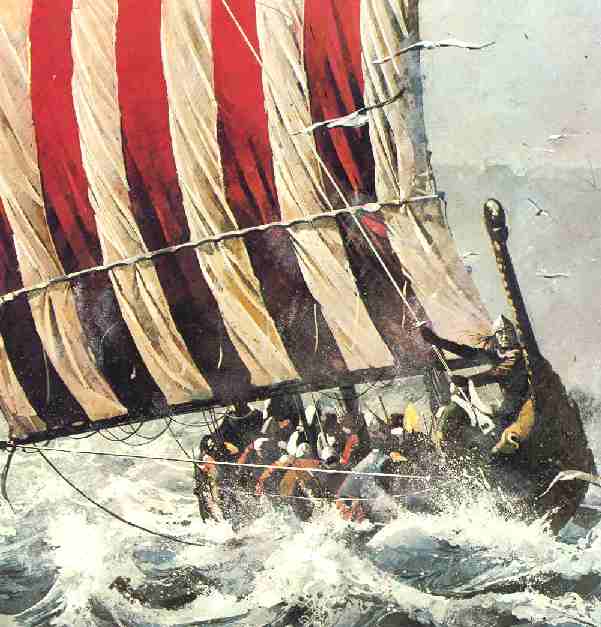

There were two distinct classes of Viking ships: the longship (the largest also known as "drakkar", meaning "dragon" in Norse) and the knarr. The longship, intended for warfare and exploration, was designed for speed and agility, and were equipped with oars to complement the sail as well as making it able to navigate independently of the wind. The longship had a long and narrow hull, as well as a shallow draft, in order to facilitate landings and troop deployments in shallow water. The knarr, on the other hand, was a slower merchant vessel with a greater cargo capacity than the longship. It was designed with a short and broad hull, and a deep draft. It also lacked the oars of the longship.

Longships were used extensively by the Leidang, the Scandinavian defense fleets. The term "Viking ships" has entered common usage, however, possibly because of its romantic associations (see below).

In Roskilde are the well-preserved remains of five ships, excavated from nearby Roskilde Fjord in the late 1960s. The ships were scuttled there in the 11th century to block a navigation channel, thus protecting the city which was then the Danish capital, from seaborne assault. These five ships represent the two distinct classes of the Viking Ships, the longship and the knarr. Longships are not to be confused with longboats.

Modern revivals

See also 19th century Viking revival. Early modern publications, dealing with what we now call Viking culture, appeared in the 16th century, e.g. Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (Olaus Magnus, 1555), and the first edition of the 13th century Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus in 1514. The pace of publication increased during the 17th century with Latin translations of the Edda (notably Peder Resen's Edda Islandorum of 1665).

Romanticism

According to the Swedish writer, Jan Guillou, the word Viking was popularized, with positive connotations, by Erik Gustaf Geijer in the poem, The Viking, written at the beginning of the 19th century. The word was taken to refer to romanticized, idealized naval warriors, who had very little to do with the historical Viking culture. This renewed interest of Romanticism in the Old North had political implications. A myth about a glorious and brave past was needed to give the Swedes the courage to retake Finland, which had been lost in 1809 during the war between Sweden and Russia. The Geatish Society, of which Geijer was a member, popularized this myth to a great extent. Another Swedish author who had great influence on the perception of the Vikings was Esaias Tegnér, member of the Geatish Society, who wrote a modern version of Friđţjófs saga ins frśkna, which became widely popular in the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom and Germany.

A focus for early British enthusiasts was George Hicke, who published a Linguarum vett. septentrionalium thesaurus in 1703–05. During the 18th century, British interest and enthusiasm for Iceland and Nordic culture grew dramatically, expressed in English translations as well as original poems, extolling Viking virtues and increased interest in anything Runic that could be found in the Danelaw, rising to a peak during Victorian times.

The German composer Richard Wagner's works are strongly influenced by Norse mythology.

Nazism

The Romanticist heroic Viking ideal and the Wagnerian mythology also appealed to the Germanic supremacist thinkers of Nazi Germany as reflected, for example, in the runic emblem of the SS, the neo-Nazi youth organization Wiking-Jugend, and its Odal rune symbol (see also fascist symbolism). The Norwegian fascist party Nasjonal Samling used viking symbolism and imagery widely in its propaganda. It is unfortunate that the Vikings were chosen, as they have absolutely nothing to do with Nazi ideology (in fact most Vikings were peaceful, and the ones that raided did so for practical reasons, not ideological ones), and German history has relatively little to do with the Vikings (except for in the Northern Baltic region, and through the same early Germanic cultural and mythological roots that also connect them to Anglo-Saxon culture).

Viking raiding party enactment

Popular myths

Horned helmets

Apart from two or three representations of (ritual) helmets with protrusions that may be either snakes or horns, no depiction of Viking Age warriors' helmets, and no actually preserved helmet, has horns. In fact, the formal close-quarters style of Viking combat (either in shield walls or aboard "ship islands") would have made horned helmets cumbersome and hazardous to the warrior's own side. Therefore it can be ruled out that Viking warriors had horned helmets, but whether or not they were used in Scandinavian culture for other, ritual purposes remains unproven. However, as no actual horned helmets have been found, the only information remains in depictions which may be interpreted in different ways, as mentioned above. The general misconception that Viking warriors wore horned helmets was partly promulgated by the 19th century enthusiasts of the Götiska Förbundet, founded in 1811 in Stockholm, with the aim of promoting the suitability of Norse mythology as subjects of high art and other ethnological and moral aims. The Vikings were also often depicted with winged-helmets and in other clothing taken from Classical antiquity, especially in depictions of Norse gods. This was done in order to legitimize the Vikings and their mythology, by associating it with the Classical world which has always been idealized in European culture. The latter-day mythos created by national romantic ideas blended the Viking Age with glimpses of the Nordic Bronze Age some 2,000 years earlier, for which actual horned helmets, probably for ceremonial purposes, are attested both in petroglyphs and by actual finds. The cliché is perpetuated by cartoons like Hägar the Horrible and Vicky the Viking. Skull cups

The use of human skulls as drinking vessels is also ahistorical. This myth must be dispelled as it furthers the misconception of Vikings as exceptioanlly barbaric. The rise of this myth can be traced back to a mistranslation of an Icelandic kenning. In the Latin translation of the Krákumál by Magnús Ólafsson (in Ole Worm's Runer seu Danica literatura antiquissima of 1636), warriors drinking ór bjúgviđum hausa [from the curved branches of skulls, i.e. from horns] were rendered as drinking ex craniis eorum quos ceciderunt [from the skulls of those whom they had slain]. (Scandinavian skalli/skalle: skal means simply "shell" and skál/skĺl "bowl".) The skull-cup allegation may have some history also in relation with other Germanic tribes and Eurasian nomads, such as the Scythians and Pechenegs (skull caps).

Personal Hygiene

The image of wild-haired, dirty savages, sometimes associated with the Vikings in popular culture, has hardly any base in reality. The Vikings used a variety of tools for personal grooming such as combs, tweezers, razors or specialized "ear spoons". In particular, combs are among the most frequent artifacts from Viking Age graves, and one can conclude that a comb was the personal equipment of every man and woman. The Vikings also made soap, which they used to bleach their hair as well as for cleaning, as blonde hair was ideal in the Viking culture (much like it is common for modern Scandinavians to bleach their hair if it isn't already blonde).

The Vikings in England even had a particular reputation of excessive cleanliness, due to their custom of bathing once a week, on Saturdays (as opposed to the local Anglo-Saxons). To this day, Saturday is referred to as laugardagur/lřrdag/lördag "bathing day" in the Scandinavian languages, though the original meaning is lost in modern speech. As for the Rus', who had later acquired a subjected Varangian component, Ibn Rustah explicitly notes their cleanliness, while Ibn Fadlan is disgusted by all of the men sharing the same vessel to wash their faces and blow their noses in the morning. Ibn Fadlan's disgust is probably motivated by ideas of personal hygiene particular to the Muslim world, while the very example intended to convey the disgusting customs of the Rus' at the same time records that they did, in fact, wash every morning.

Painting of Viking Longship at sea

In popular culture

Books

Vikings, and Viking inspired societies have appeared in a number of works of fiction, including:

Movies

Famous Vikings

Other names used to denote Vikings

Culture

Archaeology

Place names

Viking replica Longship at Chicago world fair 1893

REFERENCES and LINKS

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2017. The name Solar Navigator is a trade mark of Solar Cola Ltd. All rights reserved. Cleaner Oceans Foundation is an educational charity. |