|

ALAN SIMPSON

|

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | MUSIC | THE BOAT | SOLAR BOATS | SPONSORS |

|

27 October 2005 Morning Star - THE SLOW BURNING FUSE OF SUSTAINABILITY

ENVIRONMENT

It

is very British that a revolution that will change our lives profoundly

over the coming years actually began its course almost 200 years ago. This

is a revolution in energy policy, and it will leave the nuclear debate

looking like a discussion between sad, old fogies, arguing about the best

way to build the Maginot Line.

Alan Simpson MP - Nottingham South

This isn't pie-in-the-sky thinking. It is already happening now; and being driven by local visionaries and engineers who have metamorphosed into eco-engineers, holistic scientists and sustainability designers. The more I became immersed in the construction of my own eco-house, the more I entered a world which is both humbling and exhilarating. Some 80% of new buildings in Berlin have solar powered energy generators. Holland has installed ‘hot road' energy systems under asphalt road surfaces that provide heating/cooling for local houses. (Every 1 km of road heats about 100 houses). Toronto is replacing energy guzzling, air conditioning systems in modern buildings, with a cooling system that circulates (and returns) water from Lake Ontario . Woking , in England , has installed its own local wiring system, generates 135% of its own energy needs, and will be coming off the National Grid in the next few years.

On an even bigger scale, the Mayor of London's Climate Change Programme aims to make London energy self-sufficient within a decade, and up to 20 global cities are in discussions with London about doing the same. When you consider that London currently consumes more energy than the entirety of either Portugal or Ireland , you realise the scale of the revolution we are talking about. And not one job of the energy will come from nuclear.

Bear with me a bit while I turn the clock back to where it all began. The year was 1817, and at the junction of Water Street and what was to become Gas Street , the City of Manchester built the country's first gasworks. The revolutionary body behind this was the Manchester Police Commissioners who, 11 years earlier, had asked a local manufacturer to fit a gas lamp over the entrance to the police station. Crowds would gather at night to marvel at the piddling little flame that lit the entrance. But the Commissioners became convinced that this was the answer to their street lightning problems. In reality it became so much more.

By the time Joseph Chamberlain led Birmingham into an era that championed municipal democracy and ‘Gas and Water' socialism in the 1870s, there were already 49 municipal gas companies around the country. Leeds and Glasgow had joined Manchester as the early pioneers in a movement that grew from local visionaries rather than the national parliament.

What all of these cities did was to recognise they could deliver energy security for their citizens and use profits from the gas undertakings to fund an infrastructure of civic amenities that dramatically enhanced the quality of life for their people. Between 1852 and 1861 sufficient profits were passed from the municipal gas company to the Improvement Committee for Manchester to install its first decent public water supply system; along with the drains and sanitation network to support it.

By 1884, Birmingham had cut the price of gas to its citizens by 30% in the 10 years since its Gas Company had formed. It had also built a new recreation ground and was using gas profits, through the Municipal Water Committee, to deliver a public, clean water system.

How did all this happen? Without doubt it tapped in to a strange combination of socialist vision and the vulnerability of capitalism at the time. Then, as now, big businesses wanted access to secure and cheap energy supplies. Britain was emerging from an era of ‘shopocracy' in which the over-riding obsession of the Establishment was low taxes.

The result was low investment, short-termism, slums, cities that were health nightmares and a level of illiteracy that blighted society as much as individual lives. In exchange for energy security, industry had reached the stage where it was happier to see gas profits municipally re-invested in local infrastructures than pocketed by outside speculators. It is only what Woking , and the Mayor of London, are seeking to do now.

Virtually all of the cities pioneering this Gas and Water socialism either raised the initial money in local taxes (the Rates) or in issuing Public Bonds. If cities today offered ‘Sustainability Bonds' to do the same we would see a flood tide of money to support them. From individual households who wanted to become stakeholders in a sustainable energy future, to pension funds that wanted to protect their members from another dot.com debacle, there would be no shortage of backers. The result would be a revolution of unimaginably exciting proportions. And it is already beginning to happen.

In 1997, the small island of Sam so was designated Denmark 's ‘renewable energy island'. Now its straw and woodchip district heating plants, its wind turbines and solar power systems provide the entirety of the island's energy needs. Today's argument now is about what system replaces the notion of incineration. Do you go for gasification of wood chips, or bio-digesters (producing gas and a ‘residue' of high grade garden fertiliser) or bio-reactors (offering gas and bio-fuels)? Is the answer to look into a different direction combining wind or solar generators and hydrogen cells? It is a debate I am agnostically excited about.

All I know is that it is the way we think about today's energy systems that is hopelessly out of date. Look at any power station you pass and the billowing plumes of steam they emit are testimony to the 60% of energy inputs they throw away into the sky. Then, energy gets fed into a National Grid that leaks like a sieve. By the time the electricity gets through the ‘distributor' and ‘supplier' charges in the network, four fifths of the original energy input has disappeared. We could run the British economy simply on the energy we throw away – if only we produced and distributed it differently.

New municipal energy companies could sell energy services rather than energy consumption. In much the same way that big companies now lease their computers rather than buy them, the new energy companies could offer energy services packages to the public. For a fixed price (tied only to inflation) you could be offered micro-generation systems for your own home, alongside upgrading the energy efficiency of the home itself. If the energy company kept the surplus energy generated it might even pay them to offer to install low energy appliances throughout the house as part of the package.

It is a vision no more (and no less) radical than that offered by the Gas and Water socialists of the 19 th century. Today's challenge is to create networks of local energy systems, safe from terrorist attacks, able to survive environmental change, and light in the ecological footprint they impose on the century ahead.

In the coming month, Manchester will have another landmark. The 400ft Cooperative Insurance tower will display the largest array of solar panels anywhere in the country. As one commentator put it, the building will generate enough energy to make 9 million cups of tea a year. But its significance will be as a symbol not as the solution. The tower stands alone. If it's heating and cooling still depend on air conditioning then the developers should be shot. It if ignores the issue of water recycling it will fail to make the connections that City leaders made 2 centuries earlier. But it will still be a reminder of where we should be going if we are to catch up with European partners.

In the Netherlands , acoustic barriers along motorways are topped with solar panels that provide energy for housing and industry. Wind turbines along their A15 motorway will generate 60MW of electricity for the Gelderland province by 2010. All of the motorways in Britain could easily be lit by solar and wind energy if we simply had the vision and the political will to do so.

And that's the rub. Today's parliament is no more than a 19 th century shopocracy. Obsessed with empowering the individual, it has lost sight of the collective. The fate of the 21 st century will, however, be shaped by the politics of interdependency and not of individualism. The pioneers and visionaries who would build our New Jerusalem's are no longer waiting for a government that will not come. They are driven by an excitement that fuels itself. Grasp it, and we too may yet say “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive But to be young was very heaven”; All we need is to harness the youthfulness of our dreams rather than of our limbs. And the best thing is that we can do it together.

Alan

Simpson MP

BIOGRAPHY

Alan Simpson has been the Labour MP for Nottingham South, since 1992. Born in Bootle, Liverpool in 1948, the eldest of seven children, he has lived and worked in Nottingham for the past thirty years.

Alan graduated at Trent Polytechnic in 1972 with a degree in economics. He then worked as a Community worker and on anti-vandalism projects in inner-city Nottingham before joining the Racial Equality Council as Research Officer. He has published several books on racism, housing policy, inner-city policing, employment policy and Europe.

A Labour Party member since 1973, Alan became a County Councillor in 1985 and was the Labour candidate for Nottingham South at the 1987 General Election. Five years later, in 1992, Alan was elected to the seat with a majority of 3,181 and increased his majority to 13,364 in 1997.

In Parliament, Alan is a leading campaigner on wide ranging issues about the environment and the economy. The New Statesman dubbed him, "The man most likely to come up with the ideas". He has consistently put the multinational GM food companies on the defensive and fought for a safer, healthier environment. Alan is also involved in anti-poverty campaigns and ones supporting industrial democracy and common ownership. He is Chair of the All Party Warm Homes Group, and Treasurer of the Socialist Campaign Group.

Recently,

his opposition to hunting with hounds took him onto the Committee dealing

with the Hunting Bill, and his long-term campaign against fuel poverty

helped steer the Warm Homes Bill through the Commons.

Recently, his opposition to hunting with hounds took him onto the Committee dealing with the Hunting Bill, and his long-term campaign against fuel poverty helped steer the Warm Homes Bill thorough the Commons. Alan has been a lifetime campaigner within the peace movement and founded Labour Against The War, initially in opposition to the war in Afghanistan. This continued into opposition of the war on Iraq and represents an axis within the Labour Party that rejects the belief that military adventurism offers any long-term solutions to the problems of the 21 st century.

In 1999 Alan won the Green futures “Environmental Politician of the Year” award, and in 2003 was short-listed for the Channel 4 Politician of the Year awards. His work on safe food and sustainability ranges from local markets to anti-globalisation. He set up the Food Justice campaign in Parliament to challenge issues of food poverty in Britain, and in 2003 was nominated to serve on the Parliamentary Select Committee on Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Alan has written extensively on housing, environment, peace and economic issues. His latest pamphlet ‘Peoples Pensions' (2003) offered a radical alternative to the speculative fiasco we are caught up in today.

Passionate about sport, Alan plays for the House of Commons football team and also plays both tennis and cricket for the Parliamentary teams. A lifelong Everton fan, he was slightly embarrassed to be dubbed “the Michael Owen of the Green Benches”, as Owen plays for his rivals Liverpool.

Good Humoured, imaginative and iconoclastic, Alan tries to put colour and excitement into the politics of the 21 st Century.

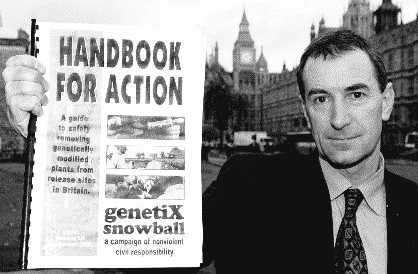

BIOTECHNOLOGY

Developments in biotechnology are raising many concerns - ecological, social, ethical - but what Alan Simpson MP sees as the most insidious result of this biotech age is it's threat to democracy.

The threat biotechnology poses to democracy may not be immediately apparent. Threats to democracy usually come in the form of out of favour dictators, not the test-tube. But I will argue that the threat is real. However, it first needs to be seen in the wider context of an economic globalisation, already heading towards collapse.

Fundamentally, the question is whether civic democracy is compatible with global deregulation, and whether the World Trade Organisation's intellectual property rights' for biotechnology discoveries will take us all into an era of corporate feudalism. The world is being spun around by big corporations who have an ability to produce more goods than the world can consume. And so, they focus their efforts on consuming each other, along with any smaller elements that get in the way.

They do this with the approval of government policy, and international treaties, which are designed to create a world fit for the corporations to dominate. This is an unsustainable state of affairs, and it takes on an even more ominous dimension when you look at the world of biotechnology.

There are two separate aspects to consider: Firstly, The nature of scientific change, and Secondly, the ownership of that change. Firstly, there is no doubt that the rate of change is breathtaking. In itself, this distorts our view about the nature of the world. We are in real danger of believing industry claims about science as a world of magic cures; that, somehow, modified genes will end all illness; or modified crops will grow in any conditions, resistant to all blight. That is arrant nonsense. It is a fundamental aspect of life on earth, that nature has never given us the gift of infallibility. Our ecosystem carries no guarantees of a world free from droughts, floods or crop failures. And by and large, the world is kept in balance by dint of this diversity. The strength of this diversity is that not all varieties of a crop get destroyed, and not all of a population succumbs to a particular illness. In general, nature also provides access to cures for the ills that it throws up.

Biotechnology is in danger of simply destroying our ability to apply this common sense to common science. And politicians are amongst the least able to grasp this. We are either invited into a knee-jerk reaction 'agin' it, on almost anti-science terms; or towards an uncritical 'yes', as part of the thoroughly modern (and pliable) parliament that industry demands. In the past we always used to be guided by the precautionary principle, that if we were not clear about the consequences of a new drug or product, public safety would over-ride commercial exploitation as the guiding principle. Now we are being driven to accept change at a much faster rate. Not because it is safer, but because some of the corporations who own patents stand to make large sums of money if they can be in the arena before their competitors. This takes me on to the second point.

My contention is that the rush into biotechnology, through patents, is, in itself, anti-research, anti-science and anti-democratic. It breaks with the traditions of research being done in pursuit of a cure, not a fortune; of farmers saving seeds, propagating plants and sharing them as protection against the larger, unpredictable forces of nature. These cures and the seeds have always been part of the global commons. Patenting has distorted our understanding of this. We are now invited to accept that unless patents are obtained, all medical and agricultural research will cease. Biotech companies have been pushing the notion of 'no patent - no cure'. Yet this is an absolute myth. They claim they need patents to protect the massive investment costs of research. Yet if you analyse the way they fund the research, you find that most of the costs, either directly or ultimately, are paid by you and I as taxpayers. It may cost billions of pounds to undertake research. But government gives companies 100% write off against tax for research costs; we give them 25% write off per year for ancillary costs; we put huge amounts of direct public grant aid into research institutes; we offer generous tax breaks over extended periods of time; and then we guarantee monopoly profits as companies sell us back the products we have subsidised all along the process. This is even before we put a cost to the voluntary contributions which come from the public in the form of their family history, medical records, blood and tissue samples, all given freely as part of the research effort.

It is a myth that the industry carries all the cost and all the risk, and therefore needs to be protected. But despite my antipathy towards patents, I am actually in favour of an experiment; one in which patents are allowed, but only on cures and treatments derived without any public contributions at all, and financed entirely by the company that wants the patent. I doubt there would be much of a queue.

The chase after patents is also damaging research. Collaboration between scientists is being reduced as they become fearful of sharing ideas. There is a new fear about someone getting there first. (S)he who holds the patent controls the routes of future research. Royalties and license fees will determine who can play the game. This is anti-democratic in the most profound terms. It destroys the basis of a democratic research community which shares ideas and can act in partnership with the public, not live parasitically off it.

It is also anti-democratic in prompting scientists to view the building blocks of life as things to be patented. This is at its most grotesque in the bio-piracy currently taking place in less developed countries.

Traditional medicinal plants, and the recipes of cures have been bought for as little as $5 in southern India. Blood samples have been taken from isolated populations and patents taken out on their cell-lines, in the belief they may hold clues to future medical breakthroughs. None of these are taken altruistically. They are taken because biotech companies see this as the short-cut to massive profits. How can they presume the right to patent someone else's cell-line, their herbs, roots or traditional medicine? We are seeing a new era of colonialism; presuming a right to take ownership of people's very existence. This is the colonisation of the soul. When we did this in previous centuries, it was called slavery. Then we landed on new shores, and declared 'terra nullius', empty lands, allowing conquerors and prospectors to set up shop wherever they wished, ignoring indigenous people's most basic human rights. Today's research companies presume the right to take patents out on fundamental aspects of nature, and ought to be asked how different they are from conquering armies who believed they could colonise land and own people. The patent is mightier than the sword in today's era of biopiracy. I see no reason why we couldn't have a different approach to this, picking up on a phrase that Tony Blair was once so keen to use, the idea of 'stakeholders'. I am a strong believer in stakeholding. We all have a stake in research funded from the public purse. So why don't we have a new concept of 'public patents' - goods permanently held in public ownership with guaranteed common access rights, and which treat the products, whether crops or cures, quite differently from the process of inventing machines. It would simply define research into our common heritage as part of the global commons.

We ought to learn to value the holding of these public patents as a cornerstone of democracy itself. Once you slip patents into the domain of private ownership, you create fiefdoms whose principal interests are to destroy any notion of democratic rights and common ownership. The global companies who fiercely defend the rights of private ownership of our biodiversity, do so in order to expropriate private profit, to undermine democracy and to enslave people.

This, I think, is the real challenge of the next century. If we do not address it, I am not sure that today's economic or political systems will themselves survive. If this is so, then the biggest crime of our time is to remain silent and inactive.

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|

|

This

website

is Copyright © 1999 & 2006 NJK. The bird |

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEBIRD | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS |