|

THE TROJAN HORSE |

||

|

HOME BIOLOGY CREW GEOGRAPHY HISTORY INDEX MUSIC THE BOAT SOLAR CELLS SPONSORS |

||

|

The Trojan War was a war waged, according to legend, against the city of Troy in Asia Minor by the armies of Greece, following the kidnapping (or elopement) of Helen of Sparta by Paris of Troy. The war figures centrally in Greek mythology and was narrated in a cycle of epic poems of which only two, the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer, survive intact. The Iliad describes an episode late in this war, and the Odyssey describes the journey home of one of the Greek leaders. Other parts of the story, and different versions, were elaborated by later Greek poets, and by the Roman poet Virgil in his Aeneid.

Ancient Greeks believed that the events Homer related were basically true. They believed that this war took place in the 13th or 12th century BCE, and that Troy was located in the vicinity of the Dardanelles in what is now north-western Turkey. By modern times both the war and the city were widely believed to be mythological. In 1870, however, the German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann excavated a site in this area which he believed to be the site of Troy, and at least some archaeologists agree. There remains no certain evidence that Homer's Troy ever existed, still less that any of the events of the Trojan War cycle ever took place.

Most historians now believe that the Homeric stories are a fusion of various stories of sieges and expeditions by the Greeks of the Bronze Age or Mycenean period, and do not describe actual events. Those who think that the stories of the Trojan War derive from some specific actual conflict usually date it to between 1200 BCE and 1300 BCE.

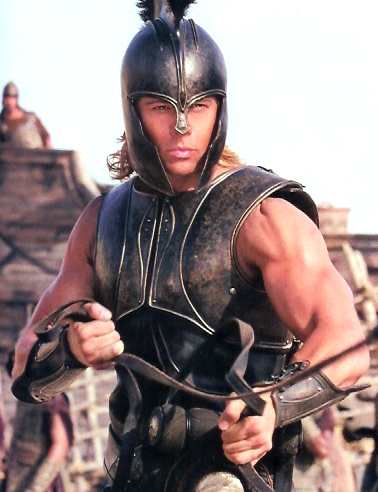

Brad Pitt as Achilles in the epic film TROY

Did the Trojan War take place? We have little reason to doubt it, but we have little more to believe that it was the greatest conflict ever to have occurred. The Greeks however, thought that it was: before telling the story of the Peloponnesian War the historian Thucydides felt the need to establish a parallel between it and the Trojan War to emphasize the importance of his subject. With the passage of time these heroic exploits had entered the realm of legend, people were convinced that the gods had taken part, and history became myth. The Trojan War glows with a dark fire at the dawn of time as the unsurpassable model for all the wars that were to come.

An extraordinary phenomenon must have an extraordinary cause. Did Homer think so? It is impossible to tell: his Iliad recounts only one episode in the conflict, the death of Hector, otherwise contenting itself with allusions or prophetic pronouncements. One thing is clear: each time the contenders started negotiations, it was said that the Trojans would have to hand back 'Helen and the treasures'. The affair started with a woman being raped and a raid -- an act of brigands. Paris went off with plundered treasure, and a queen to boot. With Aphrodite's blessing, he made the queen his wife.

But other bards, whose work has been lost, were not satisfied with such a humble explanation. They built up a cycle of epics telling the whole story of the war from the beginning. They described the origin of the affair ab ovo. They accepted that Zeus wanted to decimate the human race which had become too numerous, and posited a whole series of events: rivalry among three goddesses over an apple given 'to the most beautiful' by Eris (Discord); a verdict favouring Aphrodite pronounced by Paris, a Trojan prince brought up among shepherds; Paris being rewarded with the most beautiful woman ever seen. This woman, Helen, was the daughter of Zeus and Leda; as Zeus had disguised himself as a swan to seduce his beloved, Helen and her brothers the Dioscuri were born ab ovo -- from an egg.

This explication of the whole episode entails several difficulties. The main question is the extent to which Helen accepted the fate assigned to her. Did she act of her own free will? It was not long before people wondered if she had followed Paris voluntarily. It is an important distinction. In the first instance it could be said that she was the occasion of the war, which makes her no less odious; in the second she was responsible for the war, and could thus be hated as a scourge, and also condemned on moral grounds.

Such condemnation became increasingly necessary in the eyes of the Greeks, who were developing a personal morality, but was ever less acceptable to those among them who saw Helen as a goddess. The immorality of religious myths shocked more than one right-thinking person in the fifth century BC. In some towns, Sparta in particular, there were temples to Helen, feasts of Helen and a cult of Helen, who figured as the protectress of adolescent girls and young married women. It would be shocking if elsewhere she had set an example of adultery. And the closer we go towards presenting the story in human terms, the closer we come to the unacceptable. Aeschylus turned Helen into a being who was both abstract and divine, a sort of curse closely allied to the goddess Nemesis, -- who according to some traditions was her mother, and not Leda. But Euripides saw his heroine purely as a woman; he did not even accept the possible intervention of Aphrodite to inspire Helen with an irresistible passion. Hecabe says so very forcefully in the Troades: 'Paris was an extremely handsome man -- one look,/And your appetite became your Aphrodite. Why,/Men's lawless lusts are all called love' (v. 987, trans. Vellacott).

How far is this psychological speech, which uses allegory, also an impious speech casting doubt on the existence of the gods? It is not easy to say. In any case it is almost at the opposite pole from the chorus in Agamemnon where Aeschylus says of Helen that she is the Erinyes, the 'wife of tears' and 'the priest of Ate'; we are also a long way from the suggestion that Helen has a sort of divine mission, making her the instrument of fate: as it is expressed in Vellacott's translation, 'Was born that fit and fatal name/To glut the sea with spoil of ships' (Agamemnon 689).

The virtual disappearance of the religious aspect of Helen that surrounded her with an aura of sacred terror laid her open to the most scathing insults. People expressed amazement that the Trojan War should have been fought over such an unimportant creature -- a woman -- adding that the woman in question had absolutely no value because she herself had no sense of her own dignity. A fine assortment of insults could easily be garnered from Euripides. This tradition did not stop with him; at the height of the neoclassical period in Europe the name of Helen became a simple figure of speech, a metonym that could be used to designate any woman who was dangerous because she was flighty; in Schiller's Maria Stuart one of the queen's most persistent opponents can find no worse epithet for her than this: she is a Helen. Euripides was alive at the time when sophistry was born. No doubt he was as amused as anyone else by the idea of pleading lost causes. Gorgias and Isocrates each produced a eulogy of Helen. The tragic poet had shown them the way by putting a plea in the heroine's own mouth (Troades 903ff.). There is censure of the power of the gods, the origin of desire and the power of seduction: a suitable subject for rhetors whose prime concern it was to attract an audience. Or there is praise of beauty.

From whatever angle it was approached it was not a comfortable morality: was it possible for a woman who was perfectly beautiful to be corrupt and vile? A philosophical dimension loomed. Homer was happy to concede that the Trojan populace felt ill-will towards Helen, but the finest Trojans, Priam, his advisers and Hector, found it impossible not to respect her. At one point in the Iliad (VI.358) a strange complicity is established between Helen and Hector, both of them unhappy, but sure that they will for ever be celebrated by poets.

Homer's successors never tired of pondering a parallel between Helen and Achilles. One of the poets of the epic cycle had proposed a meeting between the most beautiful daughter of Zeus and the most valiant of heroes. Much later it was imagined that these two marvellous beings were united beyond death on the fabled Isles of the Blessed. But Euripides had already pointed out (Helen 99) that Achilles had been prominent among Helen's suitors, and that the Trojan War had been envisaged also with a view to allowing Achilles to distinguish himself (op. cit., 1. 41); moreover the apple of Discord, the origin of the whole affair, had been produced on the occasion of the wedding of Thetis and Peteus, Achilles' parents-to-be.

Paradoxically the concern to elevate Helen from the realm of sordid anecdote and restore her to an epic role, was to have the effect of casting doubt on the epic itself. Since it was vital that beautiful Helen should be virtuous, it was claimed that she had never been in Troy, that Zeus had put a phantom in her place or that a king of Egypt had snatched her from Paris to protect her. The second version, which was known to Herodotus, has had a long life: it can be found in the novel Kassandra (1983) by Christa Wolf. Wolf imagines that the Trojans pretended Helen was within their walls so as not to lose face. The first version also effectively makes Helen an object of derision, and again presents in an exaggerated form the bitter judgement so often repeated -- a woman was not a worthwhile cause for people to kill one another. Yet this was not the point of view expressed by Euripides, the poet supposed to hate women, in his tragedy Helen. Not only does he depict her character in the same touching, majestic light as his Alcestis or his Polyxena (in Hecabe), he even extends the study of the sufferings of misrepresented innocence to a tragic interrogation of the identity of the person: Helen is a woman who has been robbed of her very name and face. Saved because the gods finally proclaim the truth, she can rejoin or at least expect to rejoin the pleasant atmosphere of the feasts in Sparta (I. 141ff.), the young girls dancing and the husband towards whom she was led with songs.

Writing his 'Epithalamion of Helen' (Idylls 18) more than two centuries after Euripides, Theocritus did not even mention the Trojan War. No doubt he bore in mind that according to a tradition relayed by Plato (Phaedrus 243a) the poet Stesichorus had been blinded by the gods for speaking ill of Helen, recovering his sight only after reciting the Palinode (a recantation). It is impossible to know which of the two traditions Euripides was more committed to, that which he followed in his Helen or the other which is evident in the rest of his plays, where he attacks her as fickle, flirtatious and brazen. We can only note that other heroic characters were also depicted by Euripides in a none too favourable light: wily Odysseus, for example, whose wisdom and ability to confront the most disconcerting situations unperturbed were described by Homer with admiration, tends to become an unscrupulous sophist who loves traps and machinations. If Hecabe reproaches Helen, she does not spare Odysseus. Reading the great tragedies that conjure up the fall of Troy (Traodes, Hecabe and to some extent Andromache as well) we get the impression that the judicious balance that Homer's epic poems preserved between the two opposing sides has been upset, and certainly not in favour of the victors.

The legend also became degraded. Once seen as a divine scourge, Helen was now regarded as a hateful woman. She was the butt of obscene jokes even in Euripides' day (the Cyclops), a tradition that was continued in Horace, Jean de Meung, Hofmannswaldau, and Meilhac and Halévy. Others merely adopted a light, frivolous, scornful tone when writing about her.

The forms in which this myth is expressed are so diverse that it is hard to determine its invariables. How could we justify censuring those poets for whom Helen is perfectly and impudently at ease with her conscience, always supposing she has one? All the same, Helen is cast with remarkable frequency as a burdened soul who finds it hard to recognize her own identity, in the work of both those who stick to the Trojan version and those who adopt the Egyptian variant. One of the first times he mentions Helen Homer speaks of her 'sobs'. And the distress of the innocent Helen in Euripides' play is immense.

Beside this motif there is another: Helen is par excellence the woman carried off by a stranger. Abducted by Theseus, then by Paris, recaptured by her brothers, then by her husband, snatched from Paris by an Egyptian king, then from the son of that king by Menelaus, taken off by Simon Magus, then by Faust, sent to the heavens or to the Isles of the Blessed: is Helen the mistress of her fate?

It will be remembered that in Troades Helen is 'held prisoner with all the women taken in Troy' (1, 872). She is imprisoned like Hecabe, Andromache and Cassandra. For the film he produced in 1971 Cacoyannis had a cage built in which Helen was discovered, and suddenly booed. And in the plea she makes, however sophistical it may be, the reviled princess claim that her time spent in Troy has always been to her a period of captivity.

Morality and psychology would lead one to expect many subtle differences in the relationships between the characters. Euripides, for example, organized his tragedy round a conflict between Helen and Hecabe, and Tennyson made his poem a complaint levelled at Helen by Iphigenia. Beyond these incontrovertible specific aspects, however, one feature remains: of all the heroic chronicles that have attained the status of myth, the saga of Troy is perhaps the one in which the roles played by women were most developed. From the mourning lament in Book XXIV of the Iliad to Christa Wolf's Kassandra, taking in the highly original adaptation by Jean-Paul Sartre of Troades, a veiled figure stands over the corpses, a pitiful victim left to her fate. When the warriors have perished, the women will be dragged far away from their land to the houses of new masters. The epic of Troy tells us that a city can die.

Homer finishes the Iliad with a lament. Standing beside Hector's body Helen speaks to him, thanking him for never having insulted her. She is not afraid to compare their misfortunes; there are sensitive feelings that the old myth, facing darkness, may neglect: '. . .these tears of sorrow that I shed are both for you and for my miserable self. No one else is left. . .'.

|

||

|